What can we learn from media coverage of trauma and family separation?

by: Sarah Han

posted on Tuesday, October 16, 2018

“It’s moments like these that we have to look in the mirror and ask, who are we as a country?” – California Senator Kamala Harris

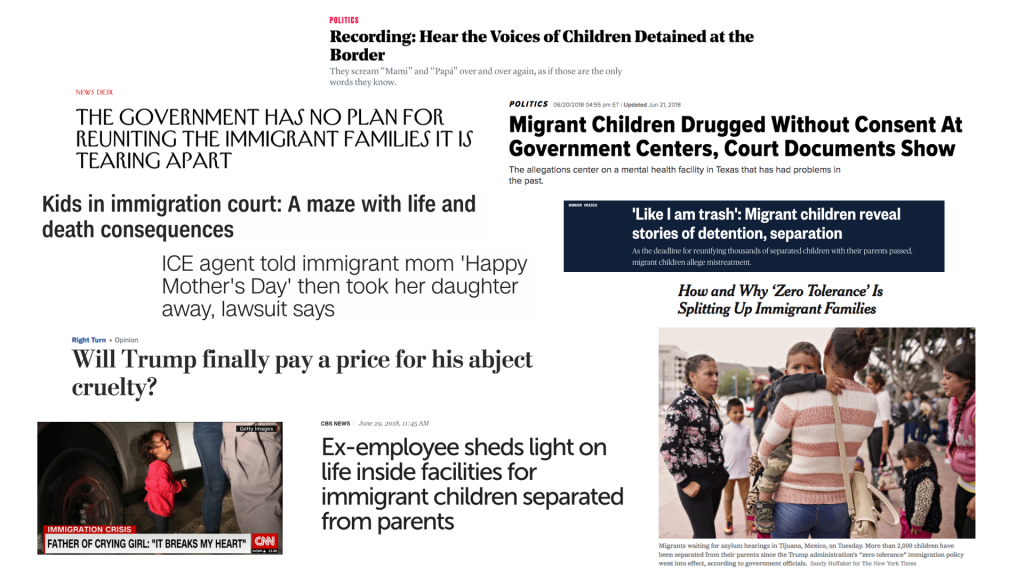

This summer, Americans confronted a moral crisis as they learned about the surge in families who are being separated and detained at the U.S.-Mexico border. In April, the Trump administration implemented a “zero tolerance policy” that treated parents arriving at the border with their children as criminals, detaining their children separately before prosecuting the parents.1 Children ripped away from their families were placed in shelters with inhumane conditions: Shelter staff were not permitted to comfort or console crying children; some were being drugged without parental consent; and despite public outcry, government officials admitted they had no plan for reuniting children with their parents. Visuals of kids sleeping in cages and on floors with foil blankets and heartbreaking audio clips of separated children crying for their parents went viral and sparked intense negative reactions and around-the-clock discussions on traditional and social media. And just this past Saturday, the Trump administration announced that it is considering a new family separation policy to deter migrants from coming to the U.S.

At the center of this public outrage is trauma: The physical, mental, and emotional health of hundreds of families and their children are being harmed. Experts and advocates for children’s health and immigrant rights have spoken out against the separation and detention of these families. “[These] children are essentially living their worst nightmare,” Wendy Cervantes of the Center for Law and Social Policy told Newsweek. “A kid’s worst nightmare is the boogeyman coming in the middle of the night and taking away their parents. That’s what’s happening.”

The American Academy of Pediatrics even released a policy statement for the protection of immigrant and refugee children’s health and well-being, urging that they be treated with dignity, respect, and the appropriate care. “We are hearing reports about children who have been detained, even for a short time, who are showing symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, depression, and behavioral problems,” said Marsha Griffin, MD, a co-author of the policy statement.

From a previous Berkeley Media Studies Group news analysis, we know that childhood trauma is rarely discussed in the news. But has it appeared more often in the midst of this intense, nationwide focus on family separations? We wanted to know, what does the coverage of trauma and family separation and detainment look like? And what lessons can advocates and journalists learn from how trauma is discussed in news coverage of family separation?

What we did

Using Media Cloud, an open-source archive of print and online news publications, we collected articles published in major mainstream and online news outlets from September 1, 2017 to September 1, 2018. We searched for and examined articles that discussed family separation and those that also mentioned “trauma,” “toxic stress,” or “adverse childhood experiences.”

What we found

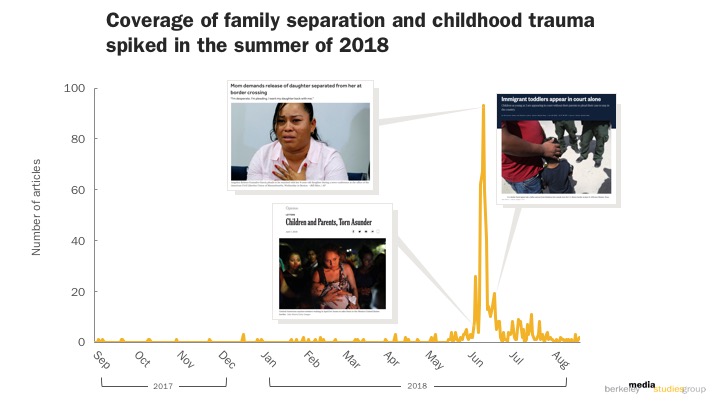

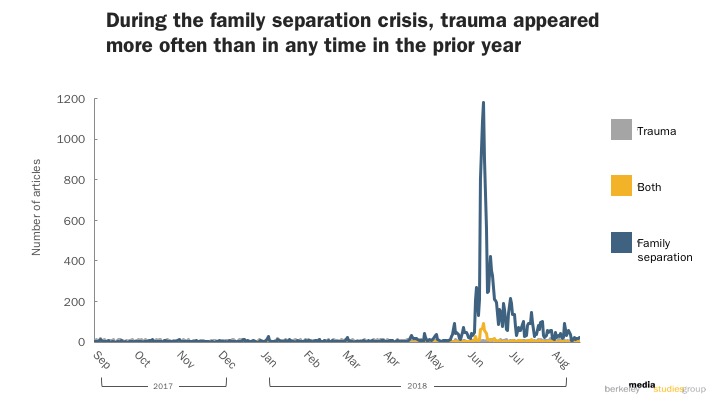

Before April 2018, there was minimal coverage about childhood trauma and family separation: Between September 2017 and March 2018, an average of three articles per month were published that discussed both childhood trauma and family separation. Then, in April, The New York Times published an article with new revelations that hundreds of children had been separated from their parents, sparking public outrage and high levels of media coverage. From April to September 2018, the average number of articles that discussed both childhood trauma and family separation skyrocketed to 130 per month, increasing nearly fortyfold. The coverage about family separation and childhood trauma peaked at 482 articles published in June alone.

Overall, we found 13,703 articles about family separation. Of these, only about 5% mentioned trauma2 (n=675). While explicit discussions of trauma only came up in a small portion of the news about family separations and detentions, compared to everyday coverage about childhood trauma, this represented a notable spike.

This coverage was not only notable because of its overall volume but because it featured a wide range of perspectives, unlike most coverage about childhood trauma, which tends to quote mostly health care representatives. Reporters sought perspectives from child health and welfare experts and advocates to describe the trauma caused by family separation and its long-term effects on children’s health. For example, a New York Times article cited a statement in which heads of the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Child Welfare League of America, along with other advocates, strongly urged the homeland security secretary, Kirstjen Nielsen, not to break up families:

“Separation from family leaves children more vulnerable to exploitation and abuse, no matter what the care setting. In addition, traumatic separation from parents creates toxic stress in children and adolescents that can profoundly impact their development.”

The broad range of speakers quoted in the news, including advocates, researchers, and elected officials, all brought different perspectives but were united in assigning blame and responsibility to the Trump administration. This stands in sharp contrast to our earlier analysis, which found that the coverage of childhood trauma focuses overwhelmingly on after-the-fact solutions, paying little attention to how institutions can work to prevent kids from being traumatized in the first place.

For example, in early June, as the coverage was reaching a fever pitch, Senator Jeff Merkley spoke with the media about what he had witnessed at a Texas detention center, where separated children were being held; he assigned complete culpability to federal policymakers:

“This is morally bankrupt and wrong on every level. You don’t hurt children in order to influence policy decision[s]. … This is not mandated by law. This is a decision that was made after extensive conversations within the administration. It’s completely at their decision to adopt this strategy.”

A Washington Post article quoted Luis H. Zayas, professor of social work and psychiatry at the University of Texas at Austin, who not only touched on the irreparable, long-term impact of childhood trauma, but also assigned responsibility for addressing the trauma to the government:

“It’s not like an auto body shop where you fix the dent and everything looks like new. We’re talking about children’s minds. Our government should be paying for this. We did the harm; we should be responsible for fixing the damage. But the sad thing for most of these kids is this trauma is likely to go untreated.”

Where to go next

The coverage about family separation is distinct in that it created the foundation for a public discussion about how we as a country can cause and prevent childhood trauma. It provides important lessons about what coverage that centers childhood trauma, systemic injustices, and the responsibilities of institutions to make necessary policy changes looks like. Explicit, nuanced discussions of childhood trauma and sharp calls for government accountability rarely appear in news, yet in the coverage of family separation, it did seem to spur action. On Wednesday June 20, faced with mounting public outrage, President Trump signed an executive order reversing his policy of separating families (although only replacing it with a policy of indefinite family detention).

However, the news about family separation and detention and childhood trauma has dropped off greatly since this summer, even as the Trump administration considers a new family separation policy and new revelations about injustices at the border continue to arise: The number of detained children has multiplied more than fivefold since March, surprise inspections of detention centers show kids living in terrible conditions, and deported parents may lose their children to adoption.

Advocates and journalists working to keep family separation in the spotlight should ensure that childhood trauma remains part of the conversation. We can’t solve a problem we don’t know is happening. Only when the news media shine a light on the devastating impacts of family separation on children and families and hold policymakers to account, can we begin the hard work of tackling family separation as not just a moral, but a public health and social justice issue.

Children’s health advocates and journalists can also apply these lessons to other issues affecting children’s well-being, such as inadequate housing, the opioid epidemic, or disparities in the criminal justice system. What is the potential for these issues to cause childhood trauma? What policies are responsible for causing or perpetuating that trauma? And how can we hold institutions, elected officials, and other decision-makers responsible for preventing it?

For more information about how to bring trauma prevention into the media conversation, see BMSG’s “Issue 24: Adverse Childhood Experiences in the News: Successes and Opportunities in Coverage of Childhood Trauma.”

Have you seen recent coverage that effectively makes the link between family separation and trauma? Let us know at info@bmsg.org, @BMSG, or on Facebook.

End notes

1. While previous administrations — including the Obama administration — had also detained families at the border (for up to 20 days, as limited by the Flores settlement 2015), none had demanded that all families be separated as the Trump administration did.

2. This count may not include all articles that discuss how family separation and detention impact children’s health and well-being because our sample only collected those that mentioned the keywords “trauma,” “toxic stress,” and “adverse childhood experiences” specifically. A more in-depth analysis would also capture implicit references to childhood trauma.