Giving effective public testimony to support health equity: 9 tips for advocates

by: Katherine Schaff

posted on Wednesday, September 25, 2019

On a recent day, I was reminded that despite being in the thick of BMSG’s daily work on media advocacy and communication, it can still be intimidating to be the one at the microphone. In my personal time outside of my work at BMSG, I had joined many other advocates at a meeting of the Rules Committee of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors to voice our concerns about proposed legislation to expand the city’s ability to confine people in a locked psychiatric facility when they are experiencing a mental health crisis — a process known as conservatorship. Currently, the process in San Francisco involves medical and mental health treatment staff at hospitals initiating a process to conserve a person when they believe that the need for potential confinement outweighs the deprivation of a person’s personal liberty. While a conservatorship law is already on the books across California, the new law transfers the impetus for conserving people from medical and mental health professionals who make decisions on medical grounds to the police and criminal justice system.

In San Francisco, like so many communities around the country, policies have put affordable, quality homes out of reach for many of our city’s residents. A lack of housing options coupled with cuts to an already limited mental health system creates severe instability in many people’s lives and makes accessing much-needed services challenging. Rather than depriving people of personal liberty, fellow advocates and I wanted to make the case for increasing services and housing options that people can access voluntarily.

But first I had to prepare my comments and get ready to speak in front of a large crowd. Fortunately, plenty of tools exist to help advocates plan and practice. While I was at City Hall, I also asked some experienced activists their advice for effectively giving public testimony. Here are nine tips that can help you or your organization do just that:Get the details for your meeting.

This was my first time giving public comment in San Francisco, and while there are similarities across jurisdictions, my first step was getting more information on the local process. I used the social media pages of organizations that had been at the forefront of organizing on this issue to stay updated on the date, time, and room number at City Hall. I checked the Rules Committee page on the Board of Supervisors’ website to see how long I’d have to speak. The time limits may be short — I was hoping for three minutes but found out we only got two — so you have to be strategic about what points to prioritize. When you arrive, you’ll likely need to fill out a comment card, indicating your agenda item number. I found mine on a handout by the door, but these are also usually available online.

Even if meetings are listed as running only a few hours, try to bring plenty of coffee, snacks, and a charged phone because meetings often run longer than planned.

Connect and coordinate with allies.

Speaking out at City Hall is just one part of a broader policy and communication strategy, and connecting with organizers at the forefront of the work can help not just with developing your comments but also with staying engaged in the campaign.

“Align with organizations and movement builders who have been doing the work as well, so that you can have more coordinated messaging,” recommended Sam Lew, the policy director at the Coalition on Homelessness. This advice held true for me — handouts from the coalition helped me determine which parts of their message I could lift up as a public health worker.

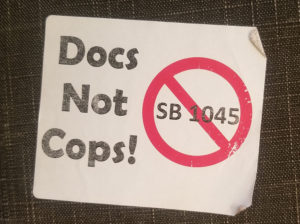

When I arrived at City Hall, I was easily able to identify allies in the fight for housing, services, and health — they were wearing “Docs not Cops” stickers and gave me one, too. Connecting to them helped me learn more about the issue, stay updated on logistics and evolving strategies, and ensure that I was supporting efforts to prioritize community members most impacted by the proposed legislation. For example, on the first day I went, organizers let us know that one of the Board members was leaving early and wouldn’t be able to hear all the comments. The organizers quickly worked to make sure people with lived experience, such as being previously conserved or facing housing instability, moved to the front of the line.

The organizations leading the efforts may also have talking points and trainings to support commenters in case reporters are at the meeting and want to interview people. If you are delivering public comments on behalf of your organization, it’s critical to know your organizational policy and whether you can speak to the media on behalf of your organization. If you are not the media contact at your organization, direct reporters to the designated spokesperson or to someone else in the coalition who is prepared to speak to the media.

Prepare and practice.

Just like playing sports or a musical instrument, there are no shortcuts with practicing public speaking. If you are like me and often have more to say than there is time for, write your comments down in advance and rehearse. Speaking out loud is always more effective than reading in your head because it gives you a more realistic idea of how long your comments will take, and it can be easier to identify what can be cut. If you still need help refining your talk, reach out to friends and colleagues. In my case, a fellow member of the Public Health Justice Collective (PHJC) helped edit my comments. I also partnered with another PHJC member to split the talking points so we could fit in our most pressing public health concerns, including how the legislation moves treating mental health concerns further under the purview of police, which is directly counter to public health research and recommendations, such as the recently passed American Public Health Association resolution on law enforcement violence and San Francisco’s own Health Commission’s resolution on treating incarceration as a public health issue.

In addition to individuals taking the time to prepare, organizations can do a lot to support their members, like developing easy-to-read handouts that include talking points and a clear description of the solution that can be incorporated easily into comments. Creating visuals — like the stickers and signs — help people find one another, connect, keep the energy up, and provide reporters with compelling imagery that can be used in news stories and shared on social media. Public meetings also give us an opportunity to flex our creativity muscles — the coalition even created a song about conservatorship that we sang as we walked through City Hall to bring attention to the issue.

Speak from the heart.

Public speaking can cause butterflies, whether it’s your 1st or your 100th time, and remembering why you are passionate about the issue can help calm your nerves.

“It can feel intimidating to be at City Hall. People in suits look like they know what they are doing, and they look very polished, but they don’t often have the real-world community experience, and that’s what elected officials need to hear,” Jessica Lehman, the executive director of Senior and Disability and Action told me. “And this is supposed to be a place for the people, right? So keep in mind that what you as a community member have to say is just as important — in fact, probably more important — than what other people are saying.”

Keeping your purpose in mind and speaking from the heart not only lowers the intimidation factor but also makes for a more compelling message.

“The times I’ve been most successful, and I’m not great at this, is when I’ve thought weeks before about how this affects me, and by the time I step in front of the microphone, it’s all clear in my mind and it’s very succinct and it just spills out,” said Michael Lyon of the Gray Panthers of San Francisco. “But you do have to think about how it affects you and what the context of all this is.”

Remember that messengers are a key part of message strategies.

Message strategies are more than just the words we choose. Messengers matter, and having people with lived experiences share their stories and how they connect to the proposed policy is essential.

“I think the biggest thing is for people to remember you’re an expert on your life and your own experience,” Lehman said. “And you don’t have to have all that data. You don’t have to have the credentials. Your lived experience is the most valuable thing to share.”

Mobilizing and supporting large numbers of people to show up at City Hall can be a big lift for organizations and coalitions. However, any investments in training and preparing messengers will pay off in the near term, as they testify now, and later as they apply their skills to the next issue. This is especially essential when working with people who will be sharing personal stories that bring up emotions and trauma.

“Since we organize a lot of marginalized communities to go up to public comment, it’s really important to prepare people for the environment of what that public comment might look like, because it is a very sterilized environment where oftentimes elected officials won’t even look at you,” Lew said. “They could be on their phone, on the computer, and dismiss you very quickly. And oftentimes you don’t get the satisfying response that you might expect. It’s also really difficult for folks with lived experience to share very personal stories and experiences and so, both before and after, we find that it’s helpful to create space for people to share how they are feeling and be able to process all of that public sharing with other people who can support them.”

Choose a frame that supports your strategy and role.

As public health workers, we can also be important messengers who share how policy decisions affect the health of our communities. Often, leading with the connections to equity and health is an important framing approach, especially when we find ourselves outside of traditional public health settings. The links between social determinants, like housing or jobs, and health may be clear to us because we’ve seen the science; part of our job is to make sure we explain these links to others. Doing so makes it easier for people to shift their focus from individuals to systems and to see why comprehensive, equitable solutions are needed.

Since we were speaking on behalf of PHJC, we kept the public health concerns front and center. We focused on three main concerns: 1) immediate health harms, which come from increased interactions with the police, disruptions of social networks, loss of property, and people being released into the same environment that lacks services, supports, and housing; 2) the threat to civil liberties and democratic processes, which undermines healthy communities; and 3) how the legislation “others” people, meaning the harmful process of using language, symbols, and laws to create a mythology that some of our residents are less deserving than others of basic freedoms and rights that are essential to health.

Because conservatorship is also a racial equity issue, many of the comments reflected that. The coalition emphasized that policies should focus on expanding access to coordinated services and housing, rather than introducing new conservatorship laws that weaken civil rights and put people with mental illness, people without homes, and Black and Brown communities at increased risk of being over-policed — a concern Supervisor Shamann Walton shared.

Lead with your values and include a solution.

Strong messages include the problem and specific solution, as well as values. For example, Lyon emphasized the need to restore and reconfigure mental health and substance use programs that had been cut. But he reinforced those policy details through appeals to fairness — and effectiveness. “[I]t is really obscene to talk about taking away people’s liberties, detaining them, forcing them into treatment, when their options for being able to actually get services they [need] have been [removed] by all these cuts,” he said, referring to a city report that showed San Francisco cut $40 million in behavioral health care between 2007 and 2012.

Similarly, Lew said that values like fairness and liberty permeate her group’s messaging, with slogans like “house keys, not handcuffs” and “community not coercion.”

Amplify your message on social media.

Social media can be a helpful tool before, during, and after the meeting. There are often hashtags that people routinely use for specific city or county meetings to live tweet the event. This can be helpful to follow for an analysis of what’s happening and to contribute to the conversation, amplifying your message to people who can’t attend in person. And because reporters will often use the same hashtags, it’s a good opportunity to learn which reporters cover an issue and to follow them on social media. You can retweet others, adding information about the public health context. Check with your organization and make sure you know what you can and can’t post in legislative meetings. If your organization doesn’t have guidelines for what you can post on social media, this would be a great opportunity to develop them.

Keep the conversation going.

In addition to providing in-person testimony, I emailed my comments to the Board of Supervisors and their legislative staff as one more way to raise my voice. I found their emails on their webpage and even heard back from a few of them. My email also led to a conversation with a legislative staffer about our public health concerns.

You can also reuse your comments by turning them into letters to the editor, op-eds, blogs, or other social media posts. Michael Lyon and I both wrote letters to the San Francisco Chronicle, and while they didn’t get published, each time I write one, I get faster, and it gets a bit easier to be concise while still capturing the context, values, and solution. The submissions are also educating the editors who screen them and help fuel the engine to get the next one in the paper.

Moving forward

While the Board ultimately voted to implement the conservatorship policy, advocates were able to introduce key concerns about implementation, win important amendments to lessen the negative impacts, and build partnerships that they will use to monitor implementation and raise concerns. They continue to use the momentum — and messaging — from this campaign to organize for longer-term strategies to increase access to voluntary services, support public and mental health approaches instead of policing, and address root causes, such as the underlying housing crisis and criminalization of homelessness.

On a personal level, showing up with my fellow San Franciscans and raising my voice reminded me that we are stronger together, and behind every policy vote, there are human lives that hang in the balance. It also reminded me that our democracy is far from perfect, but we do have tools, like public comment, that we can use to seek truly healthy communities. My goal is to continue to seek opportunities to use my voice. I hope you will join me.