Championing public health amid legal and legislative threats: Framing and language recommendations

Wednesday, August 31, 2022Introduction

Championing public health should be simple: Public health departments fight to keep us safe, and they work with community partners to transform the places we live for the better. Yet, this work is underrecognized and poorly understood — so much so that it leaves vulnerable our public health departments’ ability to do the work necessary to safeguard our communities’ health.

A concerted effort by some politicians and political bodies threatens to hollow out public health’s powers of protection. Those politicians aim to create new laws that their political allies can wield to shrink the power and authority of public health officials and agencies. This takes the form of a barrage of legal attacks: In some places, public health departments face lawsuits over vaccination and masking mandates; in others, opponents are removing and reassigning public health boards’ authority — often to those without public health expertise.

Public health practitioners must be able to respond quickly and effectively to these assaults on their mission — even in jurisdictions not currently under attack — to hold lawmakers accountable, to illustrate for community members what’s at stake, and to demonstrate the importance of public health.

Berkeley Media Studies Group (BMSG) and Real Language (RL) have a longstanding interest in strengthening narrative power for public health. Act for Public Health commissioned BMSG and RL to assess narratives around the current attacks on public health’s authority and recommend responses that will enable public health practitioners to communicate more effectively about the essential work they do. BMSG and RL reviewed current communication materials related to public health authority to identify problematic language as well as opportunities for public health workers to establish the value of public health in the context of current legal attacks.

Based on this analysis and our years of experience in strategic communication, we offer five tips for making the case for public health. Although there is no single message that will be effective for all audiences in all situations, the recommendations offer language to illuminate and uplift the role of public health as a public good. We are focused here on responding to the current attacks on public health authority, but the tips will be useful in explaining public health’s role across the many issues it touches, from climate change to chronic disease. When applying these recommendations, consider your community context and the specific audiences you are trying to reach and adjust accordingly.

Getting started: Shape your message based on your overall strategy and target audience.

Message is never first. While public health practitioners need to respond quickly and effectively to the many bills and lawsuits threatening their authority, your local context and overall strategy will influence how you construct and deliver your message. Some practitioners may be working in coalition with other community-based organizations, some might be going through legal channels, and some may be asked to lend their voice as part of a larger campaign. Each of these circumstances will shape your message.

If you are already affiliated with public health and ready to use your voice to protect it, this report is for you. Whether you are in a position to lobby directly or whether you are talking generally about the importance of public health, keep your messaging focused and be concrete about what needs to be done at this moment, whether that means setting up protections for keeping public health powers in place or whether it entails rejecting a bill that would remove public health authority and give it to a less qualified body.

When crafting your communication, keep in mind your primary audience: the decision-makers you want to persuade. These may be state legislators, county boards of health, boards of supervisors, city councils, judges, or others who may hear from you in direct one-on-one conversations, in hearings, comments, social media calls for action, or media interviews.

The most important secondary audiences are those allies and champions who can pressure your primary audience to support public health. These are people who already agree with you: Help them raise their voices and be heard. Messages that resonate with our supporters can pull in people who agree with us about the importance and value of public health but haven’t figured out how to talk about it. Since people are reluctant to voice an opinion if they think they’re the only ones who have it, message repetition is crucial. There may be allies who have yet to speak up but will do so after they hear your message multiple times.

Even so, there are going to be some people who will never be convinced and will remain staunchly opposed. Focusing efforts on that small (though vocal) audience is wasted energy. So keep in mind that while the audience for our messages defending public health is wide, it is narrower than the full population benefitting from the robust practice of public health.

Messaging recommendations

Click the plus symbol (+) next to each recommendation to learn more and to view suggestions for putting the tips into practice.

Recommendation #1: Frame public health as indispensable, using metaphors when possible.

How we frame an issue matters because it shapes how our audiences will understand what the problem is, who is responsible, and what needs to be done to fix it. Frames are mental pathways that get stronger by repetition. The more we hear an idea or a concept, the quicker our brains will go to this idea the next time we hear about it. The more we repeat frames that demonstrate public health as indispensable, the easier it will be for people to see public health’s necessary role in our society.

As we elevate the importance of public health, we have to contend with well-established frames that can challenge our conception of public health — especially rugged individualism, the idea that people can solve their problems on their own if they try hard enough. Rugged individualism is reinforced in storytelling, in the media and elsewhere, by zooming in on individual actions (what we call “portrait framing”) and obscuring the systems and policies that create the conditions in which people live. (Framing that instead makes these systems and policies more visible we call “landscape framing”). The current attacks on public health leverage portrait framing, stoke a false fear of losing individual liberties, and support a larger movement to limit the role of government — the protective and coordination roles we assign to our government agencies. All of this makes it harder for people to see that public health is essential for our well-being.

To respond to the legal attacks on public health, we must reframe the conversation with a focus on the landscape — the systems and conditions that support our collective well-being. The landscape frame is supported by values and principles such as our interconnectedness and our duty to one another and the greater good. Focusing on the landscape helps us hold the government accountable for carrying out its shared responsibility for health — which includes giving public health departments the authority to respond during health emergencies. When your messages repeat values that illuminate the landscape, you reinforce the frame that public health is indispensable for a functioning society.

Putting it into practice: Firefighting metaphors can help frame public health as indispensable.

Metaphors help our brains make sense of complex issues by taking the logic we use and assumptions we make about one familiar concept and applying that to another. The way we think and talk about fire departments is rich with opportunities to draw parallels to public health to reinforce how essential these services are.

In most areas, fire departments are a manifestation of a positive role for the government: protecting the greater good by pooling our resources together. It would be hard to think of a functioning society without a fire department. No one can put out a large house fire on their own, and fires can spread easily and harm more people if not contained by our dedicated firefighters. Fire departments also help communities put in place preventive measures, such as tree trimming, ventilation standards, and fire exits. They work with our schools and children, teaching them to take care of themselves and those around them in a fire.

“You don’t cut the fire department in wildfire season — and you don’t hamstring the public health department in a pandemic.”

Public health practitioners can borrow the logic in this thinking about firefighting and fire departments’ authority to keep everyone safe and apply it to conversations about public health departments. For example, you could extend the metaphor by saying, “You don’t cut the fire department in wildfire season — and you don’t hamstring the public health department in a pandemic.” Another example comes from “The Impact of Chronic Underfunding on America’s Public Health System: Trends, Risks, and Recommendations, 2021,” in which the authors use a firefighting metaphor to make the case for sustained investment in our public health infrastructure: Not investing in public health infrastructure, they say, is like not “hiring firefighters and purchasing hoses and protective equipment” until you are in the middle of “a five-alarm fire.”

Metaphors that evoke the parallels between fire departments and health departments, and, by extension, firefighters and public health workers, can help audiences understand the importance of supporting public health’s everyday work of fostering safety and well-being. This communication technique also shows why public health must have robust resources at the ready for us in intense emergencies like COVID.

Recommendation #2: Lead with strengths and achievements, not deficits and weaknesses.

Order matters. Whatever the context, don’t start with the problem — start with why public health is indispensable. Illustrate its strengths and avoid emphasizing weaknesses or deficits. Showcasing what public health does well and what it can do for the greater good reminds audiences of the value of public health and why it is worthy of our public resources. You can do this by describing our collective achievements and positive impacts — e.g., “more than 210 million people have been fully vaccinated,” and “Millions of lives have been saved” — along with examples from your local context.

While it is tempting to talk about the challenged state of public health as a way to sound the alarm for support, messages about how “broken” our public health system is can suggest to a listener that public health is fundamentally flawed or has been damaged beyond repair. If this is the case, why should such a terribly broken system get more funding or be protected from political attacks? Phrases such as “[these legislative attacks are] a further erosion of the nation’s already fragile public health system” can trigger a kind of reasoning that if public health is already so weak, perhaps we should let it die.

Leading with strengths establishes the indispensability frame without concession. Then, if needed, you can address weaknesses by naming the root causes of the problem. Explain that certain actors are intentionally trying to weaken public health. For example, you could say: “Our legislators’ duty is to uphold public health’s ability to respond, protect and inform our communities. This bill introduced by [name legislator] will intensify the pressure on our public health infrastructure, which is already fighting to overcome years of funding cuts.” Actively naming those actors reminds our audiences who should be held accountable for the devastating consequences these bills pose to our communities.

Recommendation #3: Boost the public’s confidence in public health by using precise, active language and compelling images that demonstrate the field’s competence.

Now that self-interested political actors are actively trying to undermine its role, it is crucial that people understand public health’s purview and why public health’s authority is necessary to keep whole communities safe and healthy. Public health agencies need to be recognized as deserving of the authority they have. An emergency requires quick responses that help communities feel confident in their leaders, strengthening trust in public health and government. Public health advocates and practitioners must speak decisively and establish that public health workers are moving quickly and responsively, with accuracy and competence.

Putting it into practice:

Demonstrate urgency and progress (not just “evolution”).

With a novel virus like COVID, public health’s knowledge and approaches will shift and adapt as our understanding grows. But when our communication changes and seems to be inconsistent, this can confuse the public and undermine confidence. It is important that the public understand that these shifts are the result of public health’s effectiveness and responsiveness. While our communication about COVID policy has often referred to the “evolution” of public health’s directives and recommendations, this language conveys change but not the direct improvement and urgency needed to respond to a life-threatening virus. More effective language to portray public health’s adaptations of messaging and recommendations would better demonstrate positive responsiveness — words and phrases such as “updating,” “strengthening,” “growing,” “improving.” When we talk about updating our messages, we reveal and reinforce the process behind the scenes for assessing the science and bringing public health’s experience to bear.

Discuss clarity and direction (not just “guidance”).

Similarly, the common public health term “guidance,” used widely in our official communication, does not convey to the public how critical it is that they take the steps being identified by public health experts to contain the virus. While some public health agencies cannot legally use the term “mandate” if one is not in place, they can still look for ways to include language that conveys clarity and firmness. You will determine, based on your context, what makes most sense; consider terms like “actions,” “steps,” “measures,” “professional opinion,” “directives,” or “orders.”

Use clear, active language that communicates urgency and responsiveness.

Help paint a vivid image of public health work that your audiences can picture, by using clear, concise, and active language wherever possible. Here is one example of how to add clearer and more active language to an already pretty-good message:

Before: Early in the pandemic, our public health workforce took quick, decisive action to protect our essential health care workers, who in turn protect all of us, by triaging masks to our hospitals. They also worked night and day to analyze the situation and make decisions based on new data and new supply chain developments, such as more cloth masks being available.

After: Early in the pandemic, our public health workforce jumped in right away to protect our essential health care workers — who protect all of us — by getting desperately needed medical masks to hospitals. They stayed on the trail of the virus 24/7, strengthening directives to urge mask use for everyone as soon as enhanced data on transmission and supplies were released.

Active verbs have large cognitive impacts on audiences and directly tie public health actions to public benefit. Whenever possible, describe public health people in action: “Community health workers deliver vaccines to keep people healthy…” or “We prevent the spread of diseases…”

Language that feels soft, equivocating, or vague chips away at the confidence we are trying to convey. Such language includes hedging terms such as “it seems like” or “we seek to protect.” These phrases separate public health from its active role in protecting the greater good. Stronger language includes “we know that …” or “we protect …”

Strong active verbs that practitioners generated during a live training session in May 2022 to describe what public health does included:

Show, don’t tell: A word about images

Another way to portray public health as competent, confident, and active is to show, not tell. The images you use on websites, social media, and other visual communication materials are opportunities to illustrate people engaging positively with public health. You might show community health workers going to people’s homes, doing outreach at a health fair, collaborating in a research lab, or demonstrating safer COVID practices at a public meeting or press conference. But take care to remember that certain images — such as the overused shot of a vaccine being injected into someone’s arm — can reduce public health to individuals receiving medical care rather than helping your audience see the broader landscape of public health.

Recommendation #4: Use plain but descriptive language so anyone can understand what’s at stake.

In all communication materials, use plain but descriptive language that any audience can easily understand. Whenever you can, eliminate jargon, abbreviations, legalese, and academic or formal language from your message. Using simple, descriptive language is particularly important when speaking to the media or in other public forums. While decision-makers may be the primary audience, the media reach the public and our secondary audiences as well, and if they understand our words, they will have an easier time repeating the messages and pressuring decision-makers.

For example, “morbidity and mortality” can be said simply as “death and disease.” If you do have to use jargon, explain what it means. Describing jargon may add length to the message, but the tradeoff is worth it if it means more people will understand you. For example, you could describe “preemption” as “states telling local governments and officials what they can or can’t do” or “it is when the state stops local communities from deciding what’s best for them,” which makes it easier to see why preemption used to thwart public health authority is problematic.

People seeking to limit public health authority paint a negative image of well-established public health laws and science-driven approaches to keeping the public safe. They also try to portray public health officials as abusing their power. To counter this, when talking about public health “authority” or public health “powers,” don’t stop there. Include clear language that explicitly names what public health has the power and authority to do for us. For example: “We must protect our public health agencies’ authority to keep us safer and healthier: to make the decisions that ensure we have clean water to drink, safe food to eat, and fresh air to breathe.”

Recommendation #5: Emphasize how these bills block public health’s job to keep our community safe and healthy.

All of the recommendations in this guide so far are about clarifying the role and importance of public health. Depicting what public health does and why its work is indispensable puts the bills and lawsuits attacking public health in context. When advocating against a bill, you will always need to describe clearly and succinctly what public health is and why its authority to keep everyone healthy must remain intact. Without getting into the weeds about the policy, you can still trigger basic frames that help explain why the bill and the actors behind it are harmful to the healthy, safe communities we all need.

One way to do this is to repeat words and phrases like “blocks,” “doesn’t let,” “stops them from,” “takes over,” “takes away,” “limits” and “gets in the way,” which will elicit in our audiences a feeling of losing or being prevented from getting something they want — in this case, the benefits public health provides to keep communities healthy, such as safe food to eat, clean water to drink, safe and affordable medication, and more.

You can also expand from the concept of blocking to other notions of stopping public health from doing its work. For example, here is a sample response to a lawsuit against Philadelphia officials that challenged their authority to enforce mask mandates. In this sample response, we emphasize that the lawsuit blocks what people need by using the familiar phrase of tying hands:

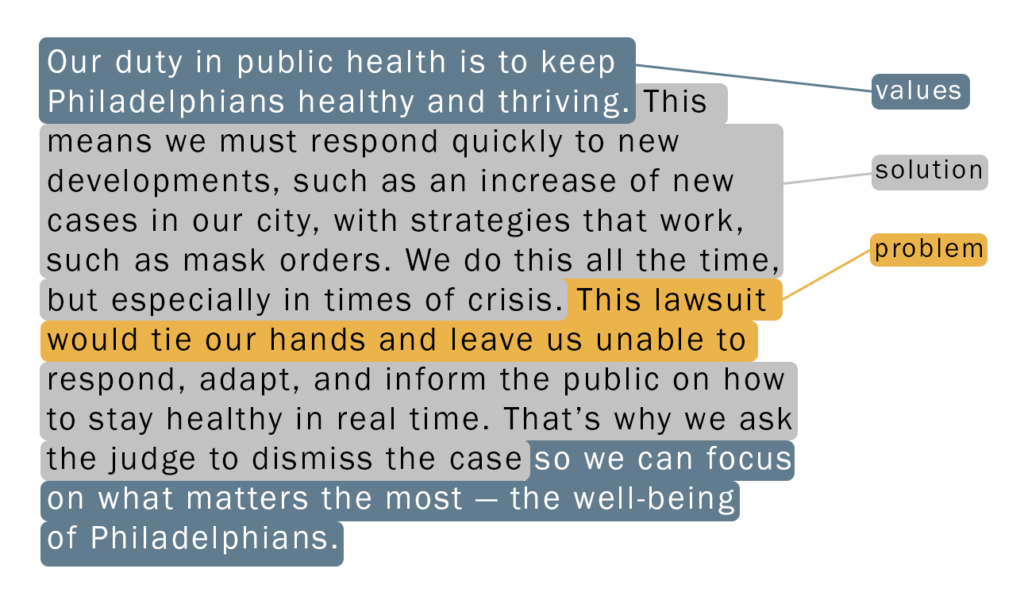

Our duty in public health is to keep Philadelphians healthy and thriving. This means we must respond quickly to new developments, such as an increase of new cases in our city, with strategies that work, such as mask orders. We do this all the time, but especially in times of crisis. This lawsuit would tie our hands and leave us unable to respond, adapt, and inform the public on how to stay healthy in real time. That’s why we ask the judge to dismiss the case so we can focus on what matters the most, the well-being of Philadelphians.

It is both deeply problematic and ironic that the bills at issue would strip authority from public health officials but leave their duty in place. In other words, society expects the results that public health provides — and politicians demand — but these bills would make achieving those results impossible. Advocates and practitioners should point that out. Using a fire department metaphor, an advocate might say something such as, “It’s like the legislature telling fire departments they must keep putting out fires but also passing a law that takes away their authority to tap hydrants — and all in the middle of a five-alarm blaze.”

You can also elevate the value of common sense by modifying the fire department metaphor above to say:

“This bill defies common sense. It’s like the state legislature piling into a bus and parking it directly in front of the hydrant in the middle of a five-alarm fire so the fire department can’t get to the resources it needs to do its job — all while making the firefighters watch while the buildings just burn to the ground.”

Strategic messaging basics: A brief refresher on key foundational tactics

Although the current threats to public health’s ability to do its job and protect our communities are more serious and intense than anything we have seen in recent history, we do not need to reinvent the wheel to produce strong messages. The recommendations above build on foundational messaging tactics that have proven beneficial with other contentious public health issues, from tobacco control to violence prevention. Below is a refresher on some key tactics that can be applied to any public health issue and are especially salient amid today’s hostile political landscape.

Remember the three components of any strategic message: problem, solution, values.

When in doubt, advocates and practitioners can always fall back on the basics, like the three components of a strategic message, for starters. The same sample message used earlier to illustrate how anti-public health legislation and lawsuits damage the field’s ability to protect our communities also demonstrates these components: a short description of the problem, a specific solution along with who is responsible for implementing the solution, and a values statement that reminds the audience why this matters. See these components highlighted in the message below:

The order of these components can change, and it is often helpful to lead with values or your proposed solution, but the individual elements remain the same.

Avoid repeating your opposition’s arguments and misconceptions; doing so may reinforce them.

Framing works by repetition and repeating the opposition’s frame would only strengthen their point and diminish yours. You can avoid this by reframing the statement to focus on the positive contribution public health makes. For example, in describing how the bills block public health action, and in answering difficult questions about it, use your own frame instead of responding to the opposition’s: State in the affirmative what public health is, who public health workers are, what you do, and why keeping your ability to do what you do matters for everyone.

Remain strategic, not comprehensive, but keep the big picture in mind.

If there is time and space to provide more information, the next step is to explain why some (not all!) of the specifics of the bill are harmful. You and your team might have a lot to say about the bill’s problems, but in brief interactions with reporters or in short testimony, you will have to focus on just a few, connected to the big picture of public health’s importance. Be prepared to answer follow-up questions, but always pair more details with your big picture description of why what public health does is indispensable in your community.

Conclusion

Public health actions meant to contain COVID may have inspired the latest attacks on public health authority, but if the attacks succeed, they will also damage every community’s ability to respond to climate change, reproductive justice, and inequities in the social factors that affect every other public health issue. Our hope is that these recommendations equip public health workers to speak passionately and effectively about their role, their expertise, and their accomplishments. We look forward to continued discussions and examples from the field that build our collective efforts to create a public health system that can ensure healthy communities for everyone.

Different question, same answer: Sample answers to difficult questions

Speaking to a reporter or a decision-maker can be intimidating. Our nervousness can make us forget what we were prepared to say, or make it hard to stay on track with our message. When you deliver your message, you’ll want to be ready to speak about the issue succinctly while sticking to your main points. Inevitably, you will get difficult questions. The best thing you can do is prepare in advance. Here are a few examples to get you started on developing answers that fit your own context and can help you stay focused on your goal of protecting public health’s authority to respond during a health emergency, regardless of the question you get.

How do you know what’s best for me and my family?

Big problems, like pandemics, demand bigger responses than any one of us can do on our own. As public health workers, we closely monitor the science so we can respond in real time to dangers that threaten the health of everyone in our community. Just like a fire department has to be well-equipped to be able to respond to a fire at a moment’s notice, health departments need to be equipped and ready, too. This is why we need to uphold public health’s authority to respond during emergencies — so we can act collectively to protect ourselves while also building healthier, safer, more equitable communities for everyone.

The “experts” keep changing their minds. Why should we trust them?

Our job is to watch the science closely so we can respond quickly when conditions change and bring the latest evidence into our recommendations. Public health workers are public servants dedicated to the greater good, who protect us from illness, disease and unhealthy conditions. By monitoring the current conditions in our community, they advise us in real time how to best protect ourselves and others. This is why we need to uphold public health’s authority to respond during emergencies — so we can act collectively to protect ourselves while also building healthier, safer, more equitable communities for everyone.

Public health officials have too much authority and shouldn’t be able to tell businesses what to do. Shouldn’t we limit their authority when it causes economic harm to our communities?

Public health officials have authority to act when the public’s health is in danger, and we take that responsibility very seriously. That means we conduct the science and assess current conditions so we can understand how health threats are affecting everyone, including the people who live and work here. We do all this so that we can make the decisions that keep us all safer and healthier, like ensuring we have clean water to drink, safe food to eat, or fresh air to breathe. We stay at the ready by monitoring disease threats. When the evidence is clear, we alert families and businesses — all the members of our communities — to take the actions that will keep us safe and healthy. The last thing we should do is tie public health’s hands – that would be like parking a bus in front of a fire hydrant, blocking the fire department from doing its job. This is why we need to uphold public health’s authority to respond during emergencies — so we can act collectively to protect ourselves while also building healthier, safer, more equitable communities for everyone.

Elected officials legislate all the time on topics in which they don’t have expertise; they have staff, they do their homework. So why can’t they do the same with respect to public health restrictions and measures?

Collectively, our public health department represents hundreds of years of study and experience, collecting and interpreting evidence and addressing complex health threats like COVID. That depth of knowledge and experience allows us to respond very rapidly to new problems. We have multi-disciplinary teams — epidemiologists, doctors, community residents, health educators — who work together and apply research findings to real-world situations. These teams have the expertise and the know-how; let’s make sure they are allowed to do their work to protect all of us from health threats. This is why we need to uphold public health’s authority to respond during emergencies — so we can act collectively to protect ourselves while also building healthier, safer, more equitable communities for everyone.

Well, if not these laws, what would provide the right checks and balances?

This question is difficult because it implies that public health is abusing its powers and that there are no checks and balances in place. To avoid reinforcing this idea and falling into the opposition’s frame the answer must pivot away from it and focus on the damaging impacts of the laws, and on the benefits public health brings to our society. We offer two sample pivots to the response that do this.

Option 1: What these laws would do is hamstring the ability of public health to do what it needs to do to keep us safe during a health emergency. We need public health departments to have the power to make decisions on how to protect our communities because they are the best equipped to do so. Collectively, our public health department represents hundreds of years of study and experience, collecting and interpreting evidence and addressing complex health threats like COVID. That depth of knowledge and experience allows our multi-disciplinary teams to respond very rapidly to new problems. We are on the ground every day — listening, living, and experiencing what our communities need. We apply the research and make the decisions that keep our communities safe. This is why we need to uphold public health’s authority to respond during emergencies — so we can act collectively to protect ourselves while also building healthier, safer, more equitable communities for everyone.

Option 2: Each branch of government has its set of complementary responsibilities. The set of responsibilities we’re talking about today sits with the executive branch for which public health carries out the duties. And for good reason: Collectively, our public health department represents hundreds of years of study and experience, collecting and interpreting evidence and addressing complex health threats like COVID. That depth of knowledge and experience allows our multi-disciplinary teams to respond very rapidly to new problems. We are on the ground every day — listening, living, and experiencing what our communities need. We apply the research and make the decisions that keep our communities safe. This is why we need to uphold public health’s authority to respond during emergencies — so we can act collectively to protect ourselves while also building healthier, safer, more equitable communities for everyone.