Talking about our recovery from COVID: How public health practitioners can emphasize equity

Tuesday, May 31, 2022Introduction

What might a truly equitable and just recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic look like? How can we build support for a robust public health infrastructure — which advocates and practitioners have long called for — so that all people have access to quality housing, child care, public transportation, and other social factors that benefit health? And what opportunities exist amid the pandemic to invest in a healthier California and address the many long-standing structural, racial, and social inequities that the pandemic has exacerbated?

In the midst of the global pandemic, climate-related disasters, and widespread actions triggered by police violence, organizations like the Bay Area Regional Health Inequities Initiative and the Public Health Alliance of Southern California have released policy platforms that envision a more equitable, just, and healthier California. Additionally, other organizations have described in depth how community-based organizations are an essential part of the public health system and played a key role in addressing inequities. These platforms and approaches go beyond addressing COVID and describe opportunities to rectify pre-pandemic inequities. Advancing such strategies — whether in response to COVID, climate change, attacks on our democracy, or other crises — will require effectively conveying these ideas to policymakers and the public, with the media being an important way to reach both.

Still, critical messages from public health practitioners and their partners that will shape if and how we move forward from COVID may not be reaching many Californians, as news about pandemic-related recovery contains significant gaps. While COVID has dominated the news during the last two years, the high volume of coverage has not necessarily increased public understanding of our public health systems, how social factors affect health, and why racial and health equity are critical for all Californians’ health and well-being. Much of the coverage about public health’s role has been incomplete, focusing primarily on mask mandates, vaccination clinics, and social distancing requirements. There has been less news about California’s public health system, which includes a vast network of community-based organizations working to rectify and prevent future inequities by overhauling systems and structures.

Local and statewide coalitions that have organizing and communication capacity can effectively shape news coverage and make a real impact on equity-focused policies.

To identify opportunities to elevate public health perspectives on an equitable recovery from COVID, Berkeley Media Studies Group (BMSG) researched news about recovery from the pandemic. We then combined our findings with additional communication research and experience working with community advocates and local health departments, to offer recommendations to strengthen communication about a just and equitable recovery — and the role that public health must play. We’ve seen how investments in building local and statewide coalitions that have organizing and communication capacity can effectively shape news coverage and make a real impact on equity-focused policies: The statewide campaign to prevent evictions during the pandemic is but one example. We hope this document supports local and state efforts to center racial and health equity as the cornerstone of California’s recovery.

Methods

Why studying the news matters: News coverage provides a window into the public narrative about any issue because news shapes public opinion and policy agendas. Journalists’ decisions about how to cover the many pressing topics of the day can raise the profile of an issue, whereas issues not covered by the news media are often neglected and remain largely outside public discourse and policy debate.1,2,3 News coverage influences how the public and policymakers perceive and discuss issues4,5 including, for example, whose perspectives are seen as credible and valuable, which solutions are elevated or ignored, and how arguments are characterized.

What we did: To identify patterns in how pandemic recovery has been characterized, and the opportunities to elevate racial and health equity in that discussion, BMSG researchers searched California print news for articles published between January 1 and September 30, 2021, that included all variations of terms like “economic recovery” or “pandemic recovery.” Our search yielded 260 articles, from which we selected a representative 20% sample of 53 articles. Of those, 28 articles (52%) substantively discussed changes to the economy or to community and social programs during the pandemic (the remaining articles either profiled the experience of individual businesses during the pandemic or highlighted only national data on the recovery not specific to California).

We evaluated the 28 articles that included substantive content using a coding instrument designed to address questions about who was quoted in the news, how pandemic recovery was characterized, and how, if at all, topics like housing, food access, or community safety were discussed. Prior to coding the sample, coders held extensive conversations to achieve consensus in how they evaluated the news. Coders also searched all 260 articles for the presence of keywords like “public health” or “small business.”

Methods citations

- Gamson W. Talking Politics. Cambridge University Press; 1992.

- Dearing JW, Rogers EM. Agenda-Setting. Sage; 1996.

- McCombs M, Reynolds A. How the news shapes our civic agenda. In: Bryant J, Oliver MB, eds. Media Effects: Advances in Theory and Research. Taylor & Francis; 2009:1-17.

- Scheufele D, Tewksbury D. Framing, agenda setting, and priming: The evolution of three media effects models. J Commun. 2007;57(1):9-20.

- Entman RM. Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm. J Commun. 1993;43(4):51-58. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.

Summary of key findings

Overall, public health practitioners’ voices are lacking in news coverage about how we will recover from the largest public health crisis of our time; that absence is especially stark when we consider how many equity-focused solutions could be relevant to this news coverage that go well beyond masks and vaccines.

Here is an overview of what we found:

- Most news articles framed the COVID-19 pandemic as an unexpected, isolated event rather than a crisis that exacerbated pre-existing inequities.

- Solutions focused on “getting back to normal” by supporting businesses, a narrow economic frame that neglects housing, paid sick leave, child care, reducing the number of people who are incarcerated, and other social determinants of health that present opportunities for rectifying inequities.

- News about the pandemic recovery often personified the economy, using language that portrayed it as a force of its own, rather than an entity connected to policy decisions that we can intervene on.

This narrow economic frame obscures the people who comprise the economy. Such coverage characterizes solutions as a matter of corporate aid, without describing how policies also need to support the workers and people who create our economy. The limited economic perspective repeatedly appeared in the news through stories that:

- evoked the needs of small businesses without defining the term,

- neglected to explain how small businesses relate to health, and

- failed to show which small-business solutions would result in more equitable health outcomes.

There are ample opportunities for the field of public health, including those in public health departments, community-based organizations, youth organizers, academics, and more, to fill this gap, reshape the discourse, and elevate racial and health equity-focused solutions in news coverage. Doing so will build support for pandemic recovery policies that go beyond a return to normal and, instead, push California to envision and enact a more equitable, just, and inclusive future.

Lakoff’s levels: A conceptual framework for developing messages

Long before the COVID-19 pandemic or the 2016 presidential election or the founding of Breitbart News, cognitive linguist George Lakoff observed a troubling phenomenon: elected officials and corporations that have transformed the narrative landscape as part of their efforts to consolidate wealth for a few while increasing inequities, taking once-fringe political ideas and making them mainstream. He noted that there are policies that promote equity, health, and a more sustainable country and world, and yet we often communicate about these in ways that are much less effective than those who oppose the policies.

Following George W. Bush’s re-election in 2004, Lakoff published a groundbreaking book to help progressives understand and reverse the trend. Eighteen years later, lessons from that book, Don’t Think of an Elephant: Know Your Values and Frame the Debate, as well as subsequent books, remain as relevant as they are urgent. While they can be applied to any public health or social justice issue, these insights are particularly useful for public health practitioners and their partners who are working across jurisdictions to align their messages and create momentum for a whole range of policy changes to support a just recovery from COVID that centers racial and health equity.

Here are a few highlights:

1. Don’t mistake policies for values.

Once you know the details of the policy you are trying to push forward, it can be tempting to start thinking of every statistic or data point that could illustrate the need for your policy. But, as Lakoff describes in Don’t Think of an Elephant, this approach is rarely effective. “Get clear on your values, and drop the language of policy wonks,” he writes, noting that policies reflect our values but are not a substitute for them in messaging. That doesn’t mean omitting all policy details; rather, before developing messages, public health advocates and practitioners must decide which shared values they want to evoke. Those values — like fairness, shared responsibility, or interconnection — are like pegs that audiences can then attach messages to.

2. Go beyond slogans.

Although jargon-filled policy statements are not effective at catalyzing widespread change, it’s also important not to swing too far in the opposite direction and oversimplify your messages. As Lakoff explains in another book Thinking Points: Communicating our American Values and Vision, clever, bumper-sticker slogans only have an effect when they are connected to — and cue up — deeply held core values.

3. Think strategically, across issue areas.

By establishing and articulating shared values, you can break through silos, remove boundaries, and illuminate a broader vision for a just recovery. “Think in terms of large moral goals, not in terms of programs for their own sake,” Lakoff urges progressives. Those opposed to social supports and public health measures tend to stay on message, no matter what. Public health practitioners can do the same, creating a basic for unity and creating messages that bridge/tie issues ranging from housing to sick pay together.

Implementing Lakoff’s lessons

What do these tips look like in practice?

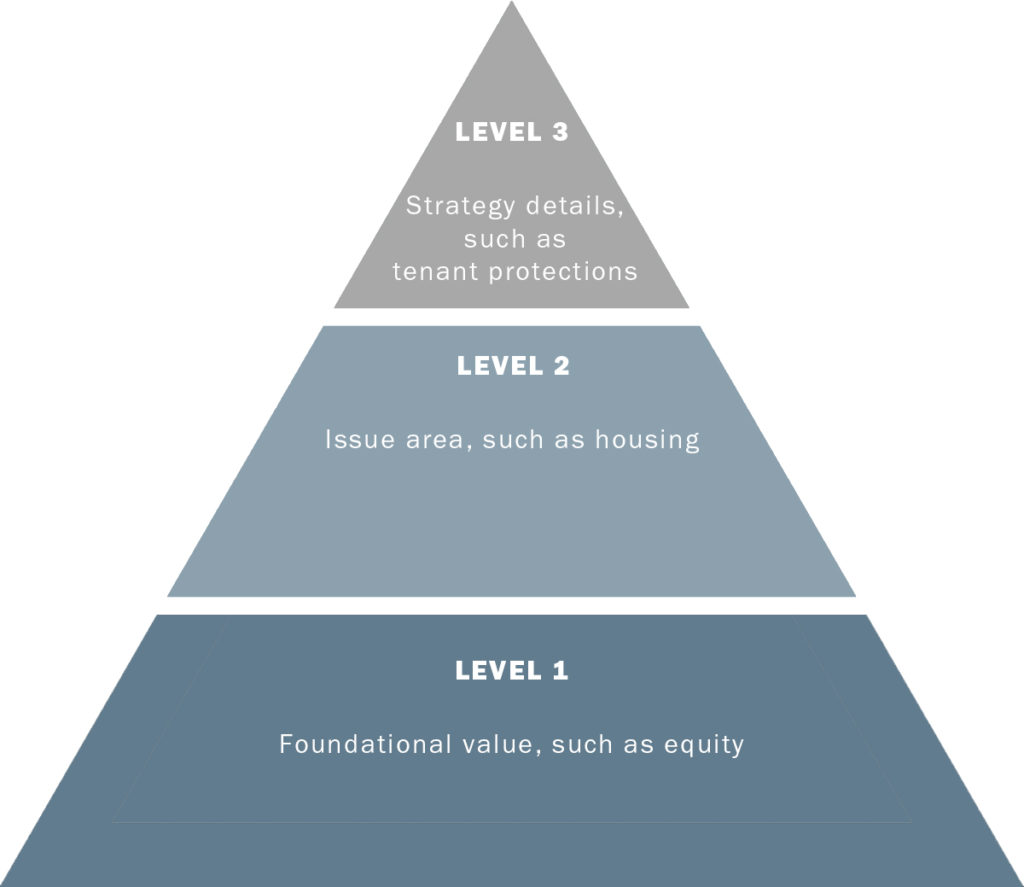

Lakoff has a conceptual framework that public health advocates and practitioners can use to align their efforts across multiple regions, departments, policies, and programs.

Start by identifying your values. Values are the foundation of the message and frame, so they comprise Level 1. If you are unsure about which values to emphasize, ask yourself questions like: Why does this work matter? Why do you show up to work every day?

Level 2 of the framework articulates the issue area. That could be climate change, jobs, Black housing, or another social determinant of health. Level 3 is about the details of your approach. What are you calling for? Who has the power to make the changes you seek? It’s common for advocates and practitioners to jump in at level three because we know a lot about the details of the policy and getting those details right is the bulk of the work. However, it’s important to create messages that pull in Level 1 elements. Doing so ensures that messages are accessible to your audience. It also brings goals from different regions into alignment and creates momentum for local health departments to use the language of a just recovery to push multiple issues across the state.

Example 1

COVID but it has also shown us what we must do to create a more equitable, inclusive, and healthy county. We’ve seen how things like funding for quality homes, schools that keep kids safe, job protections and support for local businesses that pay good wages and protect workers, and places where people can enjoy the outdoors mattered during the pandemic. But they also matter for so many other health issues, everything from diabetes to mental health. And they also matter for creating a county where everyone can thrive. We are committed to ensuring pandemic recovery funds are more than a Band-Aid for these issues and really help us partner across sectors, with residents, with local leaders, with the business community, to support these building blocks of healthy neighborhoods.

Example 2

We are at a critical moment in deciding how we move forward from the pandemic. Our recovery can reinforce the same problems that plagued our communities before the pandemic, or our recovery can be visionary and truly move us towards a just, equitable, and inclusive society where everyone can thrive. How we spend our recovery dollars now will set us up for a future where this is a reality. This is why a portion of the funds should go towards affordable housing to ensure that our residents, our neighbors, our essential workers, can live safely here. Homes matter for diabetes, for heart disease, for mental health. For happy and healthy children. And right now, because of decades of policy decisions, communities of color have been locked out of having safe, affordable, and quality homes for too long. If our city is truly committed to health for everyone, we must ensure that 35% of the recovery funds go towards affordable housing, and that the remaining funds support healthy communities, like universal basic incomes, jobs for youth, and ensuring our schools have the funding they need.

One way to think of this framework is as a Christmas tree. The star and garland and lights are like different issue areas, and the policy details are like different ornaments, but they all come together on the same tree. They are not in competition with one another but, rather, create something more beautiful than any one item could on its own.

Recommendations

Our recommendations aim to help public health advocates:

- Frame recovery in terms of people and public health, rather than using a strictly economic frame;

- Elevate equity-focused public health solutions;

- Prepare public health and community messengers; and

- Generate media attention for a just recovery.

Recommendation #1: Frame recovery in terms of people and public health, rather than using a strictly economic frame.

Action #1: Avoid language that personifies markets, sectors, or industries. Instead, name the people who make up the industries and economy, such as workers or corporate executives. Messages should focus on the power of public health to achieve health equity, which encompasses economic well-being but goes beyond supporting industries and the status quo.

What we found: Many articles emphasized the pandemic’s toll on the economy or the business sector. For example, although a number of articles mentioned the disparate impact of the pandemic (39%), many did so through the lens of specific businesses or the business sector, rather than disparities in health or economic outcomes for the most affected populations, such as low-income communities or Black, Indigenous, Latine, Pacific Islander, or Asian communities. A typical article lamented that “some industries are still reeling from the economic impact of the coronavirus [while] others, like tech, are largely returning to pre-pandemic boom times.”

News about pandemic recovery also regularly personified the economy, making it seem as if the economy acts outside of human control. We saw this in metaphors that equated the economy to a person who is reeling, recovering, faltering, struggling, etc. For example, an opinion piece from representatives of the Inland Empire Economic Partnership posited that “national and local labor markets will take longer to fully heal” compared to the Gross Domestic Product. Journalists often characterized small businesses using language that evoked human suffering, as when an article described small businesses in Santa Monica as “in crisis … [and] hanging on by a thread.”

Why it matters: Language that personifies the economy often obscures the role of decision-makers, making it harder to hold them accountable and narrowing the range of possible solutions.i Personifying industries also influences who and what are seen as deserving of recovery: This approach tees up solutions that bail out industries — or their corporate executives — rather than solutions that help the workers, and contributes to a narrative that builds support for practices that prioritize the well-being of corporate executives over workers and the public’s health.

What to do: Challenging such an entrenched and damaging narrative requires deep structural changes that go beyond communication approaches. However, one important and ongoing step that public health practitioners can take is to always be specific about the people who have been harmed during the pandemic (like grocery workers), who has financially benefited (like the CEOs of grocery chains), and what changes can improve public health. More precise language supports solutions that help those who have been most harmed.

Public health speakers should avoid personifying the economy, markets, or other forces created by humans. Instead, talk about the people working within industries that are impacted.

For example, rather than describing the local restaurant industry as “suffering,” an advocate could say, “Restaurant workers need a lot of help right now. To support them, leaders should ….” and then name a solution that explicitly supports people in that industry — for example, ensuring that companies that receive COVID funding retain and financially support their workers.

There may also be opportunities to name explicitly how policies support CEOs and industry leaders, rather than workers, and, in so doing, illustrate how social determinants of health are connected to our collective health, as well as how structural racism underlies the inequitable way they are distributed. For example, while not from the sample of articles we coded, a blog from Brookings Institute notes that “the country’s biggest grocery and retail employers have earned record profits during the pandemic — but, with few exceptions, most are sharing little of their windfall with the frontline essential workers who are risking the most.” Using precise language about the problem — CEOs reaping benefits from the pandemic while workers suffer — allows the authors to name several specific solutions, like local mandates for hazard pay, that address the needs of workers during COVID and beyond.

Action #2: Be precise in defining “small businesses” and why they matter for health. Make the people who keep the local economy moving visible in discussions of small businesses.

What we found: Corporate spokespeople, elected officials, and public health voices often use the term “small business” without clearly defining it. One-half of relevant articles named the impact of the pandemic on small businesses, and many of the solutions named in the news focused specifically on the needs of small business owners.

A typical article from the Los Angeles Times about stimulus payments around the state described grants designed to “help small businesses survive the economic downturn” and noted that the grants would supplement an existing program “that has provided 21,000 small businesses with financial help.” At times, even multinational corporations framed their pandemic recovery plans using the language of small businesses, as when a Google executive touted the company’s investment in “local communities, and the people and small businesses that give them life.”

Why it matters: “Small business” is a term that cuts across many areas of a just recovery and has long been used by corporate executives, even before COVID, to thwart policies that promote health. For example, beverage industry CEOs regularly use small business owners as the face of campaigns designed to fight sugary drink taxes intended to raise funds for community health programs;ii similarly, landlord lobbies use the idea of “Mom and Pop” landlords to push back on legislation that will reign in corporate landlords. When public health speakers use “small business” as a catchall term, they may inadvertently reflect the narrative of those opposed to equity-promoting policies. That’s why it is important for public health speakers to be clear and precise in defining small businesses, why they matter for health, and how solutions — such as a living wage benefits — that support small businesses can, in turn, support community health.

What to do: According to the Small Business Administration, a small business can have up to 1,500 employees and revenues topping $40 million — hardly what comes to mind with the term “small business,” which more likely evokes a small Mom and Pop operation.

Public health practitioners and their partners should avoid using “small business” as a catchall term; instead, they can use clear language about what small businesses are, how they serve the community, and why they matter for health. By providing a clear picture of what types of small businesses help support community health and what resources they need to move forward in the pandemic, public health voices can take more control of the narrative and make it harder for corporations to use vague language to pass regressive policies that increase inequities.

More precise language can also help practitioners make the case for solutions that sustain the small businesses that most need support.

For example, instead of saying “small businesses,” a public health speaker might specifically name “local businesses led by people of color” or “local businesses that pay a living wage and hire from the community,” a description that defines both the problem and an appropriate solution.

Recommendation #2: Name specific solutions that elevate equity.

Action #1: Elevate the root causes of inequities and talk about equity-focused solutions.

What we found: Nearly half of the articles (46%) framed the pandemic as an unexpected, isolated event that precipitated an unprecedented catastrophe. Typical language described the “economic disaster caused by the pandemic.” Only 18% of articles framed the pandemic as a catastrophe that exacerbated pre-existing inequities. A rare example came from a labor economist who described low wages and limited flexibility in service jobs as “problems before the pandemic … [that] didn’t cease to be problems now that the pandemic is over.” A few articles named the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on some communities, as when an article about the state budget noted “high income earners continue to prosper, while low-wage workers face the worst consequences.”

Why it matters: When news coverage does not reveal the connection between policy decisions and pre-pandemic inequities, it becomes harder for readers and viewers to understand root causes — and the policy solutions needed to address them. If however, news coverage identifies deep-seated injustices, spotlights decision-maker accountability, and illustrates that injustices did not start with COVID, it becomes easier for public health practitioners to tangibly illustrate how a just recovery can both address the COVID crisis and the deeper structural precursors. This creates momentum for solutions that can address inequities related to housing, jobs, wildfires and climate change, and other areas public health must tackle.

Consistently showing why we have inequities in COVID and other health outcomes related to racism, immigration status, gender, disability, and other areas also reduces the odds that people will place blame for disparities assume that individuals solely with individuals.

What to do: Public health practitioners and their partners can ensure that talking points, press releases, reports, and other communications materials frame the pandemic as a crisis that has exacerbated long-standing inequities, and name solutions to address those inequities. Advocates should develop concise talking points that pair root causes with solutions in a few sentences so, ideally, if they are quoted, journalists can take the whole quote and not leave out the solutions.

Action #2: Emphasize the necessity and promise of investing adequately in public health instead of a “return to normal.”

What we found: Most articles (82%) named at least one solution to accelerate pandemic recovery. However, most of those solutions focused on supporting businesses, although 39% of articles included at least a passing reference to housing, and 29% of articles discussed education (most often about K-12 schools reopening around the state). News articles rarely mentioned issues like food security (10% of articles), public safety and policing (14%), or public health. Indeed, though 17% of articles made some reference to public health (most characterizing the pandemic as a public health crisis or mentioning public health orders), few articles substantively discussed the role of public health infrastructure or its role in pandemic recovery.

Most articles named solutions that would enable communities to “return to normal”: Many stories, for example, discussed how budgets would be allocated or federal funds disbursed to replenish or restore existing city, county, and state systems at pre-pandemic levels of funding. Very few articles mentioned innovative or novel strategies for supporting communities in creating a better future rather than returning to the status quo. A rare example highlighted community voices in San Luis Obispo and their call to divest from police funding and reallocate resources to “address the mental health and homeless crises” in the city, concluding with a values-forward statement that “the people of San Luis Obispo deserve better.”

Why it matters: Because public health brings together so many issues and sectors (from housing to food to transportation to public safety), investing in public health infrastructure can unify stakeholders from different sectors to shift the narrative locally, regionally, and state-wide; to call for solutions at each level; and to make the case for going beyond the pre-pandemic status quo and building toward a just and equitable future for everyone.

What to do: Public health infrastructure is critical amid COVID and beyond, but many audiences will likely be unfamiliar with what “infrastructure” really means or will associate it strictly with vaccine clinics, testing sites, or mask mandates. Therefore, public health speakers must be prepared to make the case for investing in public health infrastructure using clear, precise language, definitions, and examples that illustrate what infrastructure solutions are needed that support racial and health equity locally, at the state level, and federally. This includes descriptions of how public health practices can support workers, families, and residents through universal basic incomes, eviction protections, food justice, or other interventions focused on the social determinants of health.

For example, a speaker could illustrate infrastructure and why it matters by pointing to the need for funding for trusted community groups that connect people to resources or help them participate in their local government, or measures to ensure that unhoused people can safely shelter in place.

Action #3: Frame for abundance, not scarcity

What we found: Discussions about budgets in news about the pandemic often evoked scarcity framing — the idea that there aren’t enough resources (funding, jobs, etc.) to go around, and that any resources allocated to public health or social determinants of health will be taken away from social supports. the cost of investing resources in one department or sector at the expense of another. One article from San Francisco, for example, described how “trimming the budgets of the city’s various departments to help contend with [steep] shortfalls could slow planned efforts … to reform behavioral health service.” Another article about Governor Newsom’s statewide recovery proposal included comments from an assemblymember critical of the governor’s plan to invest in electric cars, noting, “We have $1.5 billion in the budget for electric car infrastructure and incentives. We have $575 million going to small businesses. I wonder: Is that the right number?”

Why it matters: Scarcity or “zero sum” framing (which posits that if someone “wins,” someone else must “lose”), even when well-intentioned, supports an overarching narrative that ultimately undermines support for investing in communities and centering equity. A just recovery from COVID will entail investments in multiple sectors, from child care to housing to public transit. Scarcity frames make it harder to illustrate the interconnection among the social determinants of health and explain why we need to support equity approaches across sectors.

By contrast, framing for abundance can further community organizing and narrative-change goals , as doing so allows public health’s multiple partners to come together and advocate for one another. Messages that focus on reallocation of resources and resist “either/or” language can help counter scarcity framing and make the case for investing in an equitable recovery from COVID.

What to do: As part of developing their overall strategy, public health speakers must be prepared to describe solutions without reinforcing scarcity framing In other words, advocates and practitioners should challenge the frame that pandemic recovery is a competition between different sectors fighting for a “piece of the [resource] pie”; instead, frame pandemic recovery as a way to “expand the pie” for all health-promoting sectors by investing in the social and structural determinants of health.

For example, speakers can prepare for interviews with “pivot phrases” that will help them shift away from reporter’s questions that could reinforce scarcity framing, and refocus the discussion on the cross-sector benefits of investing in public health:

- “Let’s not talk about what we’re losing — let’s talk about what we’re gaining when we ….”

- “It’s important to remember that recovering from this pandemic will require a lot of different approaches — and will be most effective when all those approaches receive the support they need. That’s why ….”

Recommendation #3: Prepare public health and community messengers

Action: Develop and support a robust and diverse messenger mix.

What we found: Government representatives outside of public health departments spoke in 79% of articles about pandemic recovery. Public health department representatives were quoted in only 3% of articles. Academic speakers or researchers appeared in 20% of stories, and most of them represented think tanks like the Institute for Sustainable Development or the California Center for Jobs and the Economy.

Authentic voices — spokespeople who can provide a unique perspective on the problem (and the need for a solution) based on their lived experiences were quoted in 18% of articles. . Authentic voices often spoke about their experiences with local programs that were the subject of funding debates, as when a participant in a city-funded apprenticeship said, “[T]he program changed my life significantly in a positive way.”

Although community-based organizations have played an essential role in filling gaps in services and supporting communities, as well as building power for policy change, representatives of such organizations appeared in just 14% of articles. When they did appear, they were sometimes able to explicitly address inequities in city budgets. For example, a representative of Abolitionist Action Central Coast denounced the San Luis Obispo budget for “[failing to] reflect the needs of the most vulnerable constituents” of the city, and continued to note “we need to address the mental health and homeless crisis.”

Why it matters: The speakers quoted in news stories affect how stories are framed: The selection of speakers can elevate and give legitimacy to certain perspectives while obscuring others. Government and academic speakers can be important champions, but they may need support to talk about pandemic recovery in a way that centers equity, health, and justice.

Broadening the range of speakers beyond “expert” voices is also important because doing so expands audiences’ understanding of who the pandemic affects, why an equitable recovery is essential, and how community-based organizations often have in-depth knowledge of problems that help them generate the most effective solutions. A broad coalition that includes speakers of different ages, abilities, racial and ethnic backgrounds, immigration status, work background, etc., makes it easier to illustrate the breadth of communities impacted by the pandemic and to center equity-focused solutions, which often emerge from diverse communities.

What to do:

- Expand the range of expert speakers, including authentic voices, who can emphasize the importance of racial and health equity in our recovery from COVID.

Public health practitioners can invest in trusted, authentic messengers whose experience can lift up the importance of a just recovery. To be effective, messengers may need training in how to evoke values, name solutions, show how their lived experience relates to COVID recovery, and, if appropriate, share information about data and trends (a role that is typically limited to academics or industry representatives in the media but could easily be shared by people with lived experience). For example, a representative from a community health organization could describe how supplemental pandemic funding allowed them to build on already successful programs that reach communities facing the greatest barriers to health, share data on how COVID impacted the community, and name the need for a just recovery that includes building public health infrastructure through continued support of their organization and others like it.

- Uplift Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) as leaders and speakers.

BIPOC leadership (including youth leaders, people with disabilities, people who are unhoused, people who are immigrants, people who have been incarcerated) is crucial if our recovery from COVID is to center racial equity and ensure all Californians move forward. News coverage of COVID inequities often conveys how BIPOC communities have been harmed but less often describes the conditions and contexts that make health outcomes worse for BIPOC communities. Even rarer is coverage of the actions BIPOC communities are taking to proactively address COVID. Public health practitioners can use asset-based framing to show how BIPOC leaders and organizations are advocating for policies and approaches to COVID response and recovery that address inequities and can benefit their local community and the entire state. Advocates should prioritize expanding the range of BIPOC leaders

- Prepare all speakers to lead with equity.

Since government speakers are often quoted in news about recovery, public health practitioners and their partners must be prepared to work with government officials and their offices, as well as other speakers, to equip them to talk about solutions that put racial and health equity at the forefront and avoid harmful or problematic framing (for example, repeating opposition framing) in their public remarks.

Recommendation #4: Generate media attention for a just recovery

Action #1: Build relationships with local reporters, and provide resources to support the communication capacity of organizations in smaller media markets, where news outlets are often an untapped resource.

What we found: Almost half of articles were published in outlets from urban centers like Los Angeles (30%) and the Bay Area (17%).

Why it matters: Efforts to elevate a just recovery to decision-makers across the state will be more successful if messages are repeated in all news outlets, not just those in large media markets. Local, regional, and state policies will impact how California collectively moves forward from the pandemic, and news coverage across the state can build momentum for equity-focused policy change. It can be easier to pitch news stories and op-eds to smaller outlets as well, and these are more likely to reach local policymakers in those areas.

What to do: Public health practitioners can build relationships with their local news outlets, local organizations, and residents, who can be powerful sources for journalists. Organizations in areas outside of large media outlets may have limited resources for building their communication capacity; therefore, providing resources for organizations across the state to engage with their local media is an area where government and philanthropic support is needed.

Smaller media outlets are an untapped resource in conveying public health’s vision for a just recovery, reaching decision-makers across the state, and building statewide momentum for an equitable recovery. Public health practitioners, especially in rural areas that received less coverage about the COVID recovery, can expand the narrative by building relationships with reporters in their locales and pitching stories. Funders and state agencies could support building capacity for strategic communication in these sites. Public health practitioners in areas with higher levels of coverage on COVID recovery can track the news, including which reporters are covering the topic, and create goals for pitching op-eds and articles in these outlets that include equity-focused solutions that may be missing.

Regardless of news outlet, public health practitioners can “reuse the news,” by sharing coverage targeted toward decision-makers, funders, and other key stakeholders through email, one-on-one meetings, legislative packets, social media, etc.

Action #2: Plan for newsworthy moments.

What we found: More than half of articles (53%) were in the news because of a policy milestone, most often the announcement of a state, county, or city budget and the infusion of federal funds under the pandemic relief bill for cities. Those eager to influence the narrative on our recovery from COVID could take advantage of these opportunities for news coverage.

Why it matters: To quote legendary 60 Minutes producer Don Hewitt, “people are interested in stories, not issues.” When advocates pitch a general issue, like housing, rather than a story (e.g., a specific housing policy decision that impacts health, such as a vote on an eviction moratorium), it’s less likely that news outlets will cover the issue. Advocates can use the elements of newsworthiness (or “news hooks”) when they pitch op-eds or stories to appeal to reporters and opinion editors. Federal policy milestones often drive coverage but may not include local public health or community voices that can broaden the vision of what recovery looks like and offer local and state solutions that dovetail — or fix — federal policy.

What to do: Public health leaders should be prepared to work with their community partners to communicate with reporters as important policy milestones unfold at the local, state, and federal levels. Even federal policy milestones can serve as the “hook” for a local story by using local data, social math, or community speakers who can describe how federal budget decisions will affect the community’s or state’s ability to recover from COVID or how related local policy is also needed to ensure the resources are distributed equitably. Whatever the recovery-related issue, whether it’s public health infrastructure, child care subsidies, or supporting public transit, public health speakers can be ready to use one or more elements of newsworthiness for any pitch. For example, if journalists are covering federal policy related to housing decisions, a public health practitioner could pitch a local story about community-led efforts to strengthen local tenant protections for those impacted by COVID.

Action #3: Use opinion space.

What we found: The majority of articles about pandemic recovery (86%) were news stories; 14% of articles were opinion pieces like op-eds or letters to the editor.

Why it matters: Opinion pieces not only bring public health and social justice issues to the public’s attention but also are a way to reach policymakers, promote concrete policy solutions, and elevate the voices of public health professionals and community members. Opinion pieces are also a proactive media advocacy tool: Authors can control the framing, values, and solutions they want to elevate. Sometimes, opinion pieces can even spur news outlets to write follow-up articles that go deeper into the issues raised. Finally, opinion pieces are a space to practice and refine language about desired solutions because advocates must be concise and precise about the change they want to see, and they can reuse that language later as needed.

What to do: News outlets regularly print opinion pieces; public health practitioners and their partners should actively pitch op-eds, write letters, and talk with editorial boards. Public health practitioners and their partners can use opinion space to expand the frame or shift the narrative around our recovery from COVID and the importance of a robust public health infrastructure by submitting an op-ed, writing letters to the editor, or scheduling a meeting with a local editorial board to ask that they write an editorial.

First, if your organization has media guidelines for pitching op-eds and writing letters, familiarize yourself with them. Then, learn about the requirements from the outlet you want to reach. Work with partners who are able to pitch op-eds, or create a media strategy in which diverse authors from multiple organizations submit different op-eds to various outlets. Do not submit the same op-ed from the same authors to multiple outlets simultaneously — editors view op-eds as exclusive content. Only pitch to a second outlet if you have confirmed that the first will not be accepting your story.

Youth leaders show the way: Putting messaging recommendations into practice

This report reveals opportunities for advocates to shape the media narrative on our recovery from COVID, with recommendations to steer the conversation about recovery in ways that go beyond a “new normal” and center racial and health equity. Our findings show that advocates can use tactics like planning newsworthy moments to generate coverage, developing a diverse mix of spokespeople who can discuss pandemic recovery through the lens of personal experience, elevating root causes of inequities, showing how abstract policies and industry practices affect real people, and using asset-based framing that illustrates what we can do, instead of focusing on what we can’t.

But what does that look like in concrete terms? How can advocates move from theory to practice?

A recent article published in the Merced Sun-Star caught our attention because it offers creative examples of how to implement many of BMSG’s recommendations. To grab reporters’ attention, youth organizers began by identifying a news peg — a local city hall meeting — and planned a rally called “Fund Our Futures.” During the rally, they urged local leaders to dedicate $3 million in federal COVID-19 dollars toward underfunded priorities in south Merced that not only address COVID recovery, but also address long-standing inequities, including job creation and universal basic income for youth.

According to the article, the organizers from Power California, 99Rootz and We‘Ced Youth Media, focused heavily on solutions and painted a vivid picture of what recovery should look like. Instead of simply discussing an abstract concept like “infrastructure,” they made clear exactly how the relief dollars would be used. Besides job and income support, the funding would also go toward hazard pay for essential workers as well as affordable housing development, and the programs would be targeted at Merced residents with the lowest pay. When speaking to reporters they clearly identified their policy targets and used values like fairness.

The resulting coverage reflected their demands and included several quotes, not just from elected officials but from youth organizers whose efforts to develop strong messages — and prepare spokespeople to deliver them — paid off. The article also discussed underlying causes for local financial struggles, including the expiration of mandated COVID sick leave — context that makes it easier for readers to understand the organizers’ demands.

And, critically, organizers’ can-do spirit comes through in the article. While it’s not uncommon for coverage of serious topics like COVID and housing insecurity to create a sense of overwhelm or, worse, apathy among readers, Merced’s youth leaders championed their causes with optimism. They demonstrated that the people most affected by a problem are instrumental in addressing it and demonstrated a clear path forward, giving readers something to feel hopeful about — something to believe in.

Conclusion

We can go beyond bandaging the trauma of the past few years.

The field of public health is faced with an immense challenge — addressing the urgent needs related to COVID while looking ahead and envisioning a future where we have not only mitigated the health impacts of the pandemic but have also created a more equitable, just, and healthier California. Community groups and public health practitioners across the state and country have been developing solutions to address the root causes of racial and health inequities since long before the pandemic. The fact that these equity-focused solutions and public health voices are often missing from mainstream news about our recovery from COVID means that public health practitioners need to proactively support spokespeople, develop communication capacity, and shift the narrative toward a just recovery.

The overarching vision of a just recovery can include policy platforms, organizing strategies, coalition building, and narrative strategy that is implemented through targeted campaigns at the local, regional, and state levels that advance equity and health. While local priorities may vary, by building the capacity of California’s public health workforce to advance a vision for a just recovery, we can go beyond bandaging the trauma of the past few years. Instead, public health voices can lead efforts to envision and enact policies and practices for healing that center equity and create a more hopeful, just, and healthy future for every Californian.

References

i) Shenker-Osorio A. Don’t Buy It: The Trouble with Talking Nonsense about the Economy. Public Affairs; 2012.

ii) Nixon L, Mejia P, Cheyne A, Dorfman L. Big Soda’s long shadow: news coverage of local proposals to tax sugar-sweetened beverages in Richmond, El Monte and Telluride. Crit Public Health. 2015;25(3):333-347.