Soda tax debates in Berkeley and San Francisco: An analysis of social media, campaign materials and news coverage

Thursday, January 28, 2016In 2014, voters in the cities of Berkeley and San Francisco, California, were asked to decide whether to place an excise tax on sugary drinks sold within their borders. Berkeley made history when it passed the nation’s first tax on sugary drinks, despite an aggressive anti-tax campaign from the beverage industry. San Francisco’s measure was approved by the majority of voters but failed to reach the two-thirds majority it needed to pass.

Given the prominence of these two policy battles and the likelihood that more will follow, we wanted to evaluate social media, campaign materials and news coverage of the soda tax debates in Berkeley and San Francisco. What stories did tax advocates and opponents tell? How were the soda industry, its products and its spending characterized? Who was quoted in the news coverage, and what did they say? What lessons can the coverage offer advocates and other stakeholders seeking to improve health in their communities by regulating sugary drinks?

Why study media?

Much of what we know about the world around us comes to us through the filter of the media. Mainstream news coverage sets the agenda for public discussion and debate, shapes how we perceive and respond to social issues, and informs policymakers.1, 2 In recent years, social media has also become an important driver of news and political agendas: Social platforms like Twitter and Facebook are changing how people communicate and rally to influence election campaigns.3, 4 In addition, campaign mailers, television and radio ads have proven influential in political campaigns, affecting both voter attitudes and intent to vote.5-8

What we did

Each of the pro-tax campaigns, Berkeley vs. Big Soda and Choose Health SF, and anti-tax campaigns, No Berkeley Beverage Tax and No SF Beverage Tax (also known as the Coalition for an Affordable City) communicated their messages to potential supporters through various media channels, including social media, campaign materials such as mailers and advertisements, and the news media. To explore how campaigns communicated directly to voters, we collected and analyzed all campaign Facebook and Twitter posts, radio and television advertisements, and mass mailers. For more details about our methods, see Appendix 1.

To analyze how arguments for and against the taxes appeared in the news, we searched the Nexis news database for newspaper articles published online or in print that mentioned the Berkeley or San Francisco tax proposal. We supplemented this search with reviews of the online archives of local English- and Spanish-language newspapers not included in the Nexis database.

What we found: How soda tax proposals appeared in social media and campaign materials

What did the campaigns communicate to the public? Social media and campaign materials reveal the pro- and anti- campaigns’ key arguments in both San Francisco and Berkeley.

The pro-tax campaigns were more engaged on social media than the anti-tax campaigns.

We found 2,422 relevant tweets and 579 relevant Facebook posts published by the pro- and anti- soda tax campaigns in San Francisco and Berkeley between January 2014 and June 2015. Together, soda tax proponents in the two cities posted four times more frequently than did anti-tax representatives. In fact, pro-tax tweets and posts accounted for over 80% of the conversation on each channel (though in the month before the November election, the San Francisco anti-tax campaign did begin to overshadow the city’s pro-tax campaign). The two pro-tax campaigns used the grassroots and capacity-building nature of social media9 not only to make the case for soda taxes, but also to inform the public about events and canvassing opportunities, encourage voters to head to the polls, discuss other sugary drink policies, and in Berkeley, celebrate the victory.

A range of speakers used social media to call for soda taxes in Berkeley, while the anti-tax Twitter conversation was driven by official sources.

To learn more about the broader Twitter conversation beyond the campaigns’ posts, we also reviewed tweets containing three top Berkeley soda-tax-specific hashtags between May 2014 and April 2015: #YesonD, #BerkeleyvsBigSoda and #BerkSodaTax.

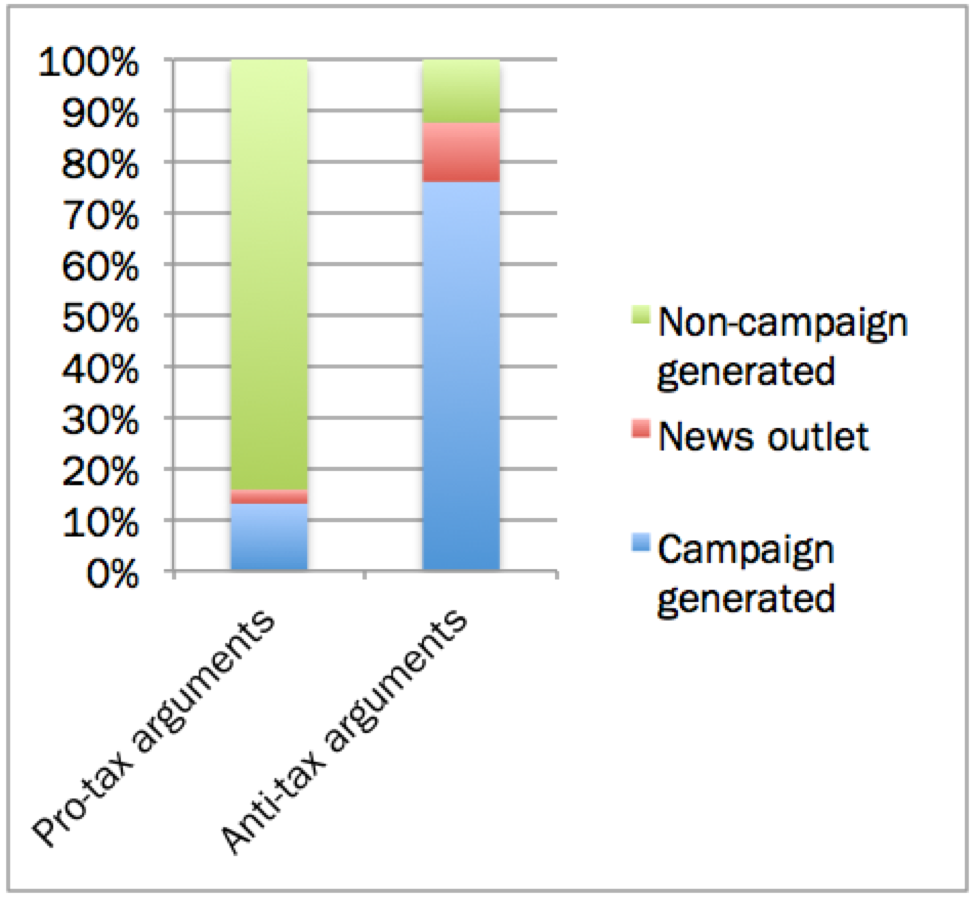

Figure 1: Generation of arguments used in Berkeley and San Francisco soda tax hashtags, 2014-2015 (n= 729)

We found that aside from the official anti-tax campaign, there were few Twitter users (15) who posted tweets arguing against the tax. Indeed, almost 80% of all anti-tax posts came from the anti-tax campaign’s @Berkeleybevtax account. Another 12% came from news outlets, as when local news site Berkeleyside live-tweeted an event and quoted representatives of the anti-tax campaign. On the other hand, there were 478 Twitter users who posted in favor of the tax, many of them Berkeley residents or members of the public health community. Interestingly, the anti-tax campaign often used the #YesonD and #BerkeleyvsBigSoda hashtags that were popularized by the pro-tax campaign.

Arguments from Twitter users in general were similar to the ones used by the tax campaigns themselves: Pro-tax tweets mostly focused on the bad behavior of the soda industry, while anti-tax tweets highlighted loopholes and exemptions.

Pro-soda tax campaigns in both cities highlighted the soda industry’s bad behavior.

Sugary drink tax proponents used social media and campaign materials to decry the soda industry’s aggressive marketing tactics and its anti-tax actions during the election. Tweets and posts spotlighting the industry’s relentless anti-tax spending began to increase in August of 2014 as the American Beverage Association (ABA) spent exorbitantly to fight the tax. In a typical Facebook post, Berkeley vs. Big Soda used social math to highlight the ABA’s unprecedented campaign spending: “Big Soda has now funneled $1.4M into defeating Measure D in Berkeley — that’s $20 per voter, more money than has ever been spent in a Berkeley election.”10

Berkeley campaign materials used strong arguments to denounce the soda industry’s anti-tax activities (see Figure 2). One quote from the Berkeley NAACP that appeared in a mailer read, “The campaign against Measure D is reminiscent of the campaigns of Big Tobacco. The amount of money they are spending in Berkeley to defeat this important measure is shameful.”11 Another drew sharp comparisons between Big Soda’s tactics and their own grassroots efforts, noting, “Big Soda has hired out-of-town canvassers and telemarketers … There is strong and unified support for Measure D from respected local businesses and individuals across Berkeley.”12 Soda tax advocates used social media to raise awareness about the ABA’s practice of paying people to protest the soda tax (see Figure 3).

Figure 2: Berkeley pro-tax campaign mailer.

Figure 3: Facebook post: Pro-tax advocate counters Big Soda rally

It is perhaps not surprising that a campaign called Berkeley vs. Big Soda would focus on industry actions, but Choose Health SF relied on such arguments as well. In fact, tweets from Choose Health SF, such as, “The ABA Isn’t Going To Tell You How Much It’s Spending To Defeat the #SanFrancisco #SodaTax …”,13 referenced industry spending more frequently than those in Berkeley (55% of San Francisco tweets compared to 42% of Berkeley tweets).

Pro-tax campaigns in both cities used health-related arguments to make the case for soda taxes.

The arguments that the campaigns used to make the case for soda taxes varied somewhat by location. Berkeley vs. Big Soda tended to focus on the health harms caused by sugary drinks (22% of arguments on Twitter and Facebook). A typical tweet read, “Sugary drinks are the #1 source of added sugars in the American diet, not foods,”14 while a mailer quoted a Berkeley reverend who pointed to research showing that “the drinking of soda and other sugar laced beverages is a leading cause of diabetes among young people.”15

In San Francisco, by contrast, social media posts tended to focus on the positive impact that a soda tax could have on community health — specifically on the potential to raise money for health programs. This was likely because proceeds in San Francisco were earmarked for prevention programming, whereas revenue from the Berkeley tax was officially destined for the general fund. On Facebook, for example, the San Francisco campaign published posts like, “The #SanFrancisco #SodaTax would help reduce consumption by an estimated 31%, and raise $35-54 million per year for kids’ health and nutrition, public health programs, and our parks.”16

Berkeley tax opponents critiqued the proposal’s structure, while in San Francisco they evoked cost-of-living concerns.

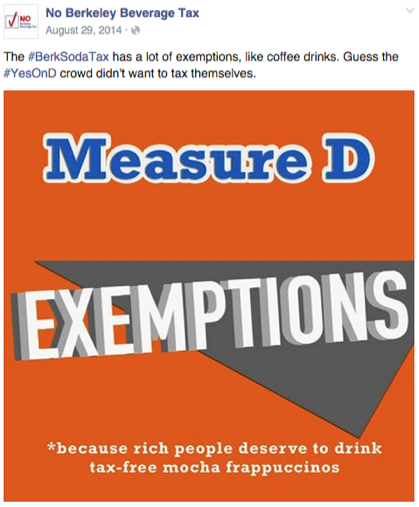

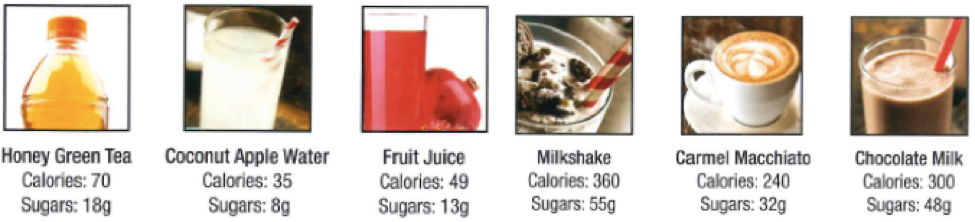

As in previous campaigns,17 anti-soda tax campaigns tailored their arguments based on the concerns of each community. In Berkeley, representatives of the anti-tax campaign characterized the soda tax ballot measure as a poorly conceived, badly-written proposal riddled with exemptions and loopholes that would tax healthy drinks and exempt unhealthy ones (as shown in Figure 4). This argument appeared in 64% campaign materials and 54% of arguments on social media. On social media, the No Berkeley Beverage Tax campaign frequently posted comments such as, “If 39 grams of sugar in a can of soda should be taxed, why not 40 grams of sugar in a blended coffee drink?”18 Campaign materials, meanwhile, frequently used the tagline “Measure D is not what it seems”19 to drive the loophole message home.

Figure 4: Berkeley anti-tax Facebook post

Berkeley’s anti-tax campaign materials also warned that because tax revenue in that city would go to the general fund, the dollars raised from the tax might not go to prevention efforts, as promised by proponents and city officials (18% of campaign materials). Anti-tax commercials in Berkeley reinforced concerns about the potential for mismanagement of funds with TV spots that featured Berkeley residents musing, “I don’t like that Measure D has the tax go into the general fund because then there’s no oversight as to where that money will be going.”20

In San Francisco, a city plagued by cost-of-living concerns and battling a housing crisis, the anti-tax campaign overwhelmingly emphasized that the tax would be an economic burden for consumers. Indeed, the local anti-tax group created by the America Beverage Association went by the name of the “Coalition for an Affordable City,” evoking local concerns about the cost of housing. The campaign highlighted this argument with tweets like “The affordability gap keeps growing. What are you going to do about it? Vote #NoOnE”21 (62% of social media arguments).

The anti-tax campaign’s physical materials echoed arguments about affordability (31% of campaign material arguments). One anti-tax mailer featured a local business owner who observed, “Right now people have a cost of living that’s going through the roof, and food is a category that should be off the table.”22 This misleading framing conflates soda with food, suggesting that the tax would increase the prices of necessities. Other campaign materials went one step further and warned that the tax would be especially financially ruinous for low-income communities or communities of color (26% of campaign materials). For example, television and radio ads targeting Spanish and Cantonese-speaking populations pointed out that residents who earn less than $20,000 per year would pay $7 million of the $37 million that was expected to be raised by the tax.22

After the tax passed, Berkeley’s pro-tax campaign highlighted how the victory could set a precedent for other communities.

Berkeley soda tax supporters used social media to celebrate their city’s pioneering victory with tweets and Facebook posts predicting that the tax would set a precedent for other cities (53% of that month’s Berkeley vs. Big Soda tweets and 50% of the campaign’s Facebook posts). In one typical Facebook post, for example, Berkeley vs. Big Soda linked to a Huffington Post article and described the city as a “trendsetter” that would inspire advocates across the nation to take action against soda in their communities.23

Pro-tax campaign materials featured a range of supporters, while anti-tax materials relied on official language.

Berkeley’s pro-tax campaign materials prominently featured a range of community representatives, including speakers from community-based organizations (18%), city officials (12%), public health advocates (9%), and other local stakeholders, including religious leaders, medical practitioners and researchers. Similarly, the materials frequently included endorsements from a range of groups representing local interests, such as Latinos Unidos de Berkeley, and the local League of Women Voters chapter. The mailers also listed endorsements from local businesses (including restaurants and grocery stores) and from groups associated with education (such as the American Federation of Teachers or local Parent Teacher Associations), and with health and health care (like the American Heart Association or the Berkeley Dental Society).

By contrast, the Berkeley anti-tax campaign materials contained few statements from speakers outside the campaign and no endorsements. Sixteen percent of arguments in the materials came from speakers identified as city residents, but there were no businesspeople, city officials, or other speakers quoted.

San Francisco’s anti-tax materials featured a slightly broader range of speakers, mostly local business owners, who accounted for about a quarter of the arguments featured (24%). Other statements came from city officials (21%, mostly comments made by supervisors during debates about the proposal) and city residents (8%).

Children and people of color were prominently depicted in pro-tax, and some anti-tax, campaign materials.

The Berkeley pro-tax campaign commonly used images of youth and communities of color. The Berkeley campaign’s logo itself featured silhouettes of children, and children were also prominently featured in TV advertisements, which highlighted how children are affected by the health harms of soda consumption (Figure 5). Adults or children of color were depicted in about half of the Berkeley pro-tax campaigns’ materials.

Figure 5 (below, left): Berkeley pro-tax TV ad highlights the effect of soda on children’s health. Figure 6 (below, right): Some anti-tax materials used images of people of color

On the other hand, none of the campaign materials from the Berkeley anti-tax campaign included images of children or youth. People of color appeared more often in San Francisco’s anti-tax materials (50% of materials) than in Berkeley’s (20%) (Figure 6).

In Berkeley, tax opponents painted a picture of loopholes and confusion.

To underscore arguments that framed the tax as poorly written and confusing, Berkeley tax opponents relied on images of “healthy” beverages that would be taxed, placed in contrast with higher-calorie, more sugary beverages that would not be taxed (Figure 7). The opposition campaign also evoked confusion with images of perplexed, frustrated men (Figures 8, 9). One image was then repurposed by the pro-tax campaign, which pictured the same man in a different colored shirt in materials used to counter the anti-tax arguments and clarify details of the tax (Figure 10).

Figure 7: Tax opponents highlighted exceptions through graphics

Figures 8 and 9: The anti-tax campaign used images of “confusion” to highlight the bill’s inconsistencies. Figure 10 (below, right): The pro-tax campaign reappropriated these images to demonstrate that there was no reason to be confused.

How soda tax proposals were portrayed in news coverage

With an understanding of how campaigns framed their messages, we turned to the news to see how arguments disseminated by the campaigns and others appeared in the larger public conversation and whether or not other arguments emerged. We found 918 newspaper articles published about the tax campaigns between October 2013 and June 2015. From those articles, we selected a representative sample of 279 newspaper articles that meaningfully covered soda tax proposals in either city.

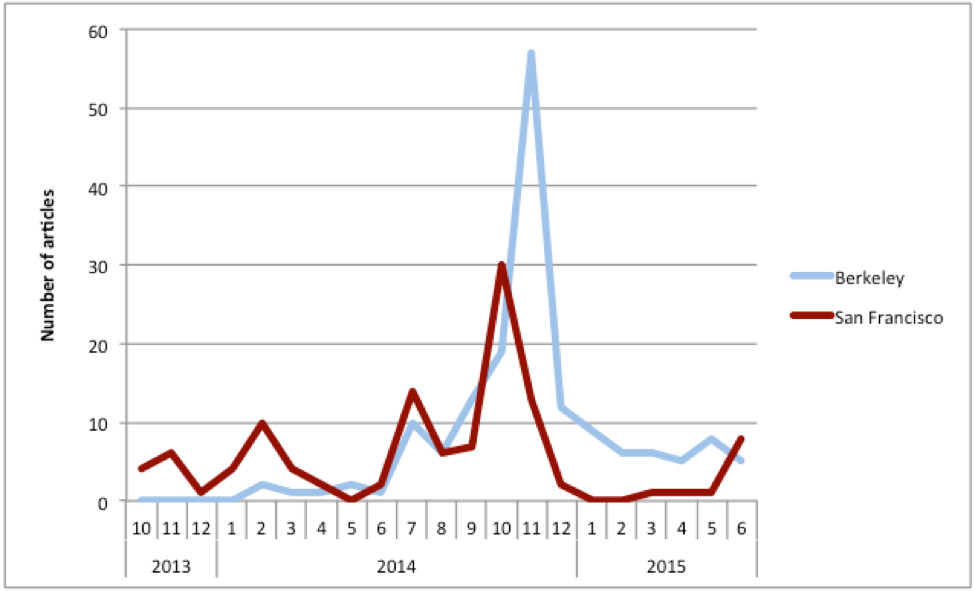

Prior to the election, the measure in San Francisco received more news coverage than did Berkeley (62% vs 38%). In both cities, coverage spiked around election time, particularly in Berkeley; the number of articles about the Berkeley tax doubled during November. In San Francisco, on the other hand, where the tax did not pass, coverage spiked in October, the month before the election. After November, news coverage overwhelmingly focused on Berkeley’s historic victory — post-election, 83% of articles focused on Berkeley (see Figure 11).

Opinion pieces comprised half of the articles from both cities, and roughly half of those opinion pieces, including unsigned editorials, were in favor of the tax. This is in stark contrast to the earlier California soda tax campaigns in Richmond and El Monte, where there were no editorials from local newspapers supporting the tax.24

Figure 11: News coverage of soda tax debates in Berkeley and San Francisco,

October 2013 – June 2015 (n=279)

Pro- and anti-tax speakers in the news differed markedly by city.

When pro-tax arguments appeared in news about the Berkeley proposal, they were usually voiced by members of the Berkeley vs. Big Soda campaign, including retired Berkeley Public Health Officer Vicki Alexander, school board member Josh Daniels, and others (44% of speakers). Other speakers who were regularly quoted included public health advocates, city officials, clinicians and community residents. San Francisco pro-tax arguments in the news were spoken most often by city officials, mostly the San Francisco supervisors who proposed the tax (18% of arguments), followed by public health advocates and community residents.

Berkeley anti-tax arguments were usually voiced by campaign spokespeople and representatives of the beverage industry, (e.g. the American Beverage Association), which accounted for almost three-quarters of the speakers. In San Francisco, campaign representatives also frequently appeared in the news voicing anti-tax sentiments (40% of arguments), but there was also representation from the business community (20%), as well as city officials (18%) and residents (7%). The business community’s engagement in San Francisco stands in sharp contrast to Berkeley, where business representatives hardly contributed to the debate (7% of anti-tax arguments).

Big Soda backing was not explicit in Spanish-language news.

In both cities, the majority of anti-tax arguments in the news were from representatives of the beverage industry. In San Francisco, the American Beverage Association funded the “Coalition for an Affordable City,” a prominent voice in opposition to the tax. Reporters in English-language publications typically made the link between the soda industry and the Coalition explicit. However, in Spanish-language news, this was not the case. In the handful of local Spanish-language news articles about the issue, journalists never reported the connection between these two organizations and quoted the Coalition at face value. For example, El Mensajero, a San Francisco based Spanish-language newspaper, quoted Roger Salazar as the “spokesperson for the No on E campaign,” (“vocero de la ‘Campaa No a la E”)25 without making any mention of the soda industry’s backing.

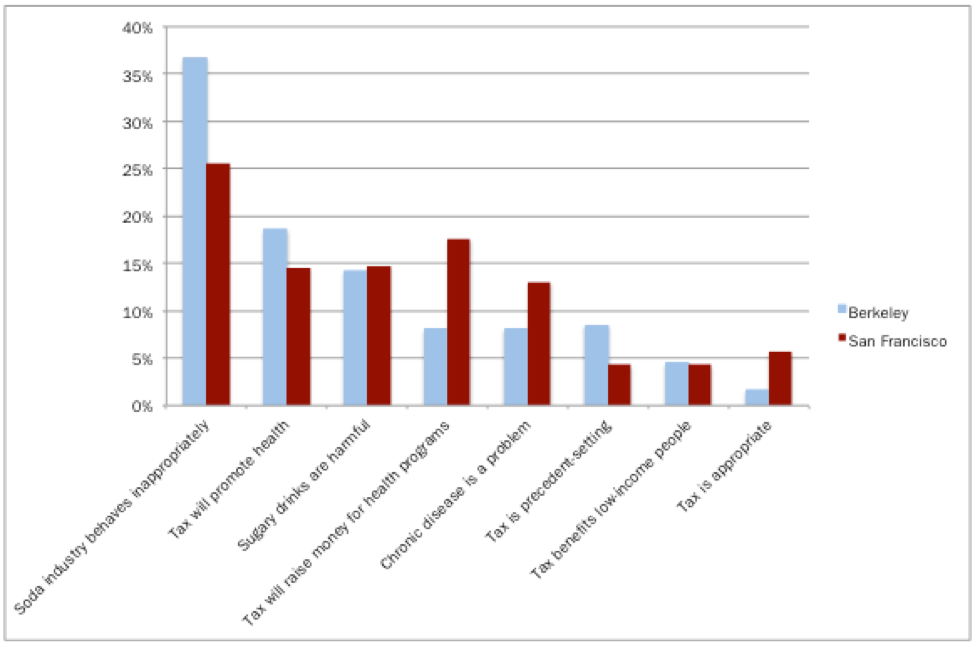

Prior to the election, pro-tax arguments in news about both cities denounced industry tactics and predicted the taxes would benefit community health.

Before the election, 61% of news arguments were supportive of soda taxes. In both cities, articles frequently emphasized the negative actions of soda companies and industry spending on the anti-tax campaign (37% in Berkeley, 26% in San Francisco). This argument became particularly prominent in September (a month after it appeared in social media), as soda companies increased their spending to counter the tax. For example, Scott Wiener of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors expressed his dismay at the soda industry’s history of “waltzing into any community that tries to address the health problems caused by soda with millions and millions of dollars and big-footing these communities.”26

Speakers quoted in the news also regularly used health arguments to make the case for the soda tax, pointing out that it would raise money for health programs, as when Dana Woldow of the San Francisco news site Beyond Chron praised the tax for helping to “raise money to help communities all across the City combat the deleterious effects of sugary drinks.”27 Similar to the pattern in social media, statements about the potential for the tax to raise money for health programs appeared more frequently in San Francisco coverage (18%) than in Berkeley coverage (8%), likely reflecting the fact that unlike in Berkeley, the revenue from San Francisco’s tax was earmarked for specific health programs. In Berkeley, tax advocates more often spoke in general terms about the tax’s potential to improve health, or to reduce consumption, as when Berkeley’s Ecology Center declared, “We are part of a wide grassroots effort, fighting for the health of the next generation.”28

Proponents of the tax also emphasized that sugary drinks were harmful to health (14% Berkeley, 15% San Francisco), and described the burden of chronic disease (8% Berkeley, 13% San Francisco) When articles mentioned the harmful effects of sugary drink consumption, diabetes (34% of articles) and obesity (38%) dominated the coverage. Heart disease was mentioned in only 7% of articles while oral health was mentioned even more rarely (2% of articles).

Other less commonly used pro-tax arguments were that the tax was an appropriate government intervention (2% Berkeley, 6% San Francisco) and that the tax would not hurt the economy (0% Berkeley, 1% San Francisco).

Figure 12: Pro-tax frames in news coverage in Berkeley and San Francisco, as a percentage of total pro-tax arguments (n=248, Berkeley; n=352, SF)

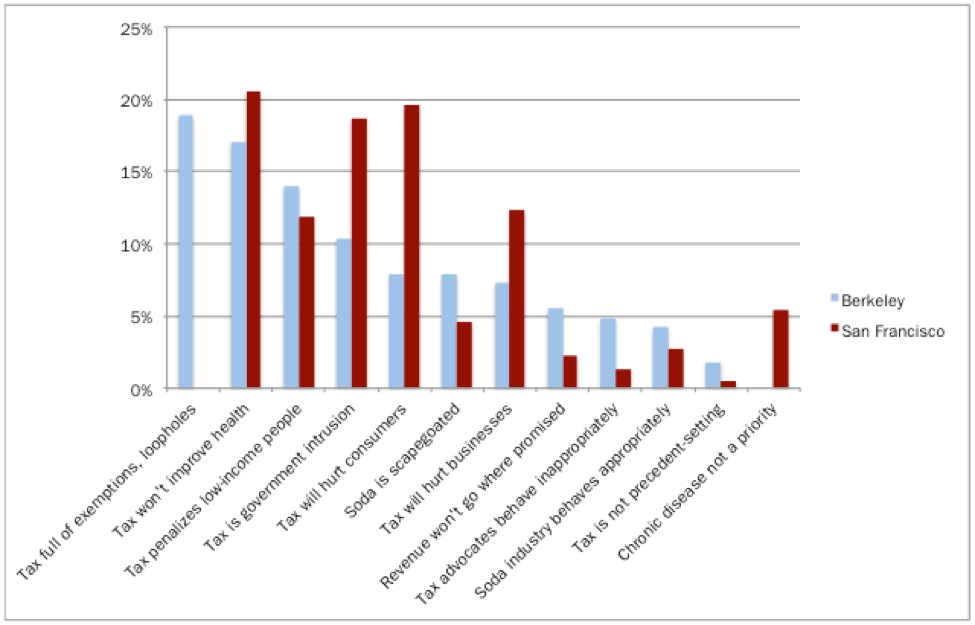

Prior to the election, anti-tax arguments in news about San Francisco emphasized affordability, while news about Berkeley focused on “loopholes.”

News coverage reflected the anti-tax campaign’s differing arguments based on location. Capitalizing on concerns about the remarkably high cost of living in San Francisco, almost 20% of the arguments against the San Francisco initiative claimed that the tax would hurt consumers. For example, the soda-industry’s Coalition for an Affordable City argued that the tax would “further [increase] the cost of living — for soda drinkers and non-soda drinkers alike — at a time when affordability is the issue of main concern in San Francisco.”29 Anti-tax advocates also harped on the possible implications for businesses, which they argued would endure a financial blow from the tax. For example, anti-tax advocate Baylen Linnekin asserted that “the small-business entrepreneurs, the taco trucks,”30 would be the hardest hit by the measure.

Articles about the San Francisco initiative were also more likely to frame the tax as government intrusion, as when an opinion author declared, “Most of us believe that it is up to the individual, rather than government, to make decisions about food choices.”31 Other anti-tax speakers argued that the proposal would not make people healthy. The industry-funded Coalition for an Affordable City was one of the most vociferous critics, claiming “a new tax that raises grocery and restaurant prices is exactly the wrong policy approach.32

Anti-tax arguments in news about the Berkeley proposal focused on “loopholes”: namely, the idea that healthy products would be taxed while unhealthy ones would not. For example, opinion writer Kathryn Stepanski called the tax a “war on random beverages with sugar in them.”26 This argument never appeared in news about the San Francisco soda tax.

Less commonly used arguments against the soda tax were that the soda industry was behaving appropriately in the campaign (4% Berkeley, 3% San Francisco) and that soda was unfairly scapegoated as a cause of health problems (8% Berkeley, 5% San Francisco). Other arguments that were occasionally utilized were that tax advocates behaved inappropriately (5% Berkeley, 1% San Francisco), and that the revenue from the taxes would not go where they claimed it would (5% Berkeley, 2% San Francisco). A small percentage of anti-tax representatives went as far as to assert that chronic disease was not a priority (0% Berkeley, 5% San Francisco).

Figure 13: Pre-election anti-tax frames as a percentage of total anti-tax arguments (n=164, Berkeley; n=219, SF)

Speakers on both sides debated the racial and socioeconomic implications of the soda tax.

Mentions of race and socioeconomic status appeared in 19% of the articles. Arguments highlighting the impact of sugary drink consumption on communities of color accounted for just 4% of pro-tax arguments in each city, but they were often powerfully framed: Supervisor Malia Cohen, for example, was frequently quoted as saying, “Bullets are not the only thing killing African American males. We also have sugary beverages that are killing people.”33

Tax opponents in both cities also evoked concerns about race and class, usually to claim that the tax proposals were regressive and would most harshly affect communities of color and low-income individuals (13% of total anti-tax arguments). For example, according to Roger Salazar of the ABA-funded Coalition for an Affordable City, “[The tax would disproportionately] impact … lower-income communities, punishing the very communities they purport to try to help.”34

After the election, speakers in the news debated whether the victory in Berkeley would set a precedent.

The Berkeley soda tax passed on Nov. 4, 2014, after which the news often included arguments from speakers who argued that Berkeley’s successful tax would set a precedent, inspiring other cities to follow suit with policies of their own (26% of pro-tax arguments after election). In a story published in Beverage World, public health advocate Jim Krieger called the victory “a breakthrough moment,”35 while Peter Foster, editor of The Telegraph, framed the victory as the start of a national movement: “Berkeley has an uncanny track record of predicting the future when it comes to social trends.”36

Opponents of the tax were quick to counter this argument, however. In a typical statement, Christopher Gindlesperger, spokesperson of the American Beverage Association, claimed, “By no means does this vote portend a trend. Activists picked the lowest-hanging piece of fruit on their quest for discriminatory taxes.”37

Conclusions

Examining social media, campaign materials and news coverage of Berkeley and San Francisco’s soda tax debates offers opportunities to understand how pro- and anti-tax campaigns framed their arguments and how this translated into the public dialogue. Together, we found:

Tax proponents called out the soda industry’s inappropriate behavior.

In the pro-tax campaigns’ direct communications as well as in the news, the soda industry’s actions were a main point of focus, mirroring the shift seen in tobacco control beginning in the early 1990s, as public health advocates increasingly focused on “denormalizing” the tobacco industry and it’s harmful products.38, 39 Previous research suggests that these arguments were particularly effective — in our case study of Berkeley vs. Big Soda’s social media efforts, we found that users on Facebook and Twitter were far more likely to like, share, favorite, retweet, and/or comment on posts that discussed the soda industry’s problematic behavior.40 Prevalence of this argument gained momentum in August 2014 on social media, followed by the news in September, suggesting the potential of social media to influence news agendas.

Anti-tax campaigns adapted arguments based on local contexts, and this was reflected in the news.

In San Francisco, the soda industry exploited the city’s existing concerns about affordability and even called its local anti-tax front group the Coalition for an Affordable City. In Berkeley, a city known for its support of progressive initiatives, the soda industry’s campaign focused on exemptions and loopholes, essentially arguing that the tax didn’t go far enough to improve health.

Adapting arguments to local contexts and unique community concerns is a common soda industry tactic: In Telluride, Colorado’s 2013 soda tax campaign, industry-funded speakers evoked the town’s spirit of individualism and argued that soda-related health consequences like obesity were not a local problem.17 In 2012, the industry framed a proposed tax as paternalistic and discriminatory toward low-income residents of color in Richmond, California, a town with a history of racial divides. In El Monte, California, a city on the brink of bankruptcy, the local American Beverage Association front group highlighted the government’s financial mismanagement and framed its proposed tax as a money grab.24

Advocates should expect anti-tax proponents to craft arguments specific to their local community. As we have seen, the soda industry is quick to adapt to local contexts and harness residents’ unique concerns to fight tax proposals. Advocates must be ready to respond to these tax-opposing arguments to shape the debate.

Pro-tax arguments included a greater variety of voices than tax-opposing arguments.

Analyzing speakers through Twitter hashtags, endorsers in campaign materials and voices in the news, we found tax supporters were able to include a more diverse set of speakers in the debate than opponents — likely a reflection of extensive grassroots organizing efforts in both cities. Stakeholders speaking for the tax included public health advocates, city officials and a variety of community organizations, medical professionals and residents. This was in contrast to previous tax campaigns, particularly those in Richmond and El Monte in 2012, where there were few voices supporting the tax aside from city officials.17

Across media, tax proponents highlighted the “astro-turf” nature of the anti-tax campaigns.

Choose Health SF used social media to expose how No SF Beverage Tax was pretending to have grassroots support. In English-language news, reporters frequently mentioned that the anti-tax campaigns were funded by the soda industry. However, when Spanish-language news reporters quoted the anti-tax campaigns, they never mentioned their ties to the soda industry.

In a marked departure from prior local soda tax efforts, there was a dramatic increase in the number of editorials in support of the tax.

Half of the unsigned editorials supported the tax in the Berkeley and San Francisco campaigns. In contrast, during the Richmond and El Monte campaigns that happened two years prior, not a single newspaper editorial was in favor.24 The increase in support for the Berkeley and San Francisco campaigns suggests a shift in the media landscape around sugary drink regulation.

Berkeley directly responded to the anti-tax campaign’s criticism of the tax’s exemptions.

Berkeley vs. Big Soda was quick to counter the opposition strategy used in that city of harping on supposed loopholes. When the anti-tax campaign used images of a confused man to suggest that there were “peculiar exemptions” in the tax, the pro-tax campaign mimicked that image in campaign mailers and countered the argument by quoting the League of Women Voters, The Berkeley NAACP, and the Berkeley Federation of Teachers, all saying that they supported the proposed tax.

Oral health was not emphasized as an argument for sugary drink taxes in Berkeley or San Francisco.

Tax proponents were more likely to focus on diabetes and obesity as health consequences of sugary drink consumption; we found little mention of tooth decay and oral health impacts. Advocates could expand their focus on the health benefits of the tax by discussing the multitude of health concerns associated with sugary drink consumption, including oral health.

Berkeley’s tax setting a precedent for other cities was a key point of debate after the election.

With Berkeley being the first city in the U.S. to pass a sugary drink tax aimed at addressing obesity, advocates and tax proponents were quick to shift post-election conversations on social media and in the news toward the fact that Berkeley’s tax is the vanguard for a larger movement in support of sugary drink policies. We also witnessed industry responses to this argument as they began to call Berkeley an anomaly and outlier in an aim to rebut its import as a trendsetter.

Final thoughts

Ten years ago, passing a measure like Berkeley’s Measure D seemed inconceivable. However, as Berkeley and San Francisco have demonstrated, public opinion can be swayed, and media advocacy can play a key role in shifting the debate about soda taxes. Berkeley set a powerful precedent that can be replicated nationwide, and San Francisco found majority support even though its tax did not pass. We expect to see a flurry of local soda tax victories as campaigns build off of these and the next wins.

Appendix on Methods

Social media: For our social media analysis, we used Twitonomy and Facebook analytics to examine tweets and Facebook posts from the Berkeley and San Francisco pro- and anti-tax campaigns’ user accounts between January 2014 (when the campaigns first began posting) and June 2015. We also used Crimson Hexagon to download tweets and selected three popular hashtags specific to the Berkeley soda tax: #YesonD, #BerkeleyvsBigSoda and #BerkSodaTax, and analyzed tweets by all users including these hashtags between May 2014 and May 2015.

Campaign materials: We acquired mass mailers from the campaigns that were on file with the City of Berkeley and the City of San Francisco, and downloaded the TV and radio ads for each campaign, which were posted online on the campaigns’ websites and on YouTube.20, 41 We examined a total of 39 campaign pieces in English, Spanish and Cantonese, including 19 physical mailers, 15 videos/television ads and five radio ads for Berkeley’s pro- and anti-tax campaigns and San Francisco’s anti-tax campaign. San Francisco’s tax proponents did not use mass mailers or ads due to limited funds.

News coverage: To obtain news coverage, we searched the Nexis news database for newspaper articles published online or in print between October 2014 and June 2015 in all U.S. news sources archived in Nexis that mentioned San Francisco or Berkeley, as well as the words “tax,” “Measure E” or “Measure D” within 75 words of “soda,” “soft drink,” “fizzy drink,” “sugary drink,” “sugary beverage,” “sugar-sweetened drink” or “sugar-sweetened beverage.” We supplemented this search with reviews of the online archives of local English- and Spanish-language newspapers not included in the Nexis database. We then sampled a third of English articles to analyze. Since we identified only a small number (n=7) of Spanish-language news pieces, we included all of these in our analysis.

Coding news, social media and campaign materials: To determine how the news articles, social media posts and campaign materials were framed, we first read a small number of stories and developed a preliminary coding instrument based on our previous news analyses of soda tax proposals in Richmond and El Monte, California, and Telluride, Colorado.17, 24 The final instrument captured pro- and anti-tax arguments and the speakers who appeared in news coverage. Before coding the full sample, we used an iterative process8 and statistical test (Krippendorf’s alpha9, ≥ .8 for all measures) to ensure that coders’ agreement was not occurring by chance.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded in part by the Global Obesity Prevention Center at Johns Hopkins University, the Voices for Healthy Kids program, a joint initiative of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the American Heart Association, and the UC Berkeley Food Institute. Thanks to Aron Egelko for research assistance and Heather Gehlert for copyediting.

Authors: Alisha Somji, MPH(c); Laura Nixon, MPH; Pamela Mejia, MS, MPH; Alysha Aziz, BA, RN; Leeza Arbatman, BA; Lori Dorfman, DrPH

© 2016 Berkeley Media Studies Group, a project of the Public Health Institute

References

- McCombs M. & Reynolds A. (2009). How the news shapes our civic agenda. In: Bryant J., Oliver M.B., (Eds). Media effects: Advances in theory and research. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis. p. 1-17.

- Scheufele D. & Tewksbury D. (2007). Framing, agenda setting, and priming: The evolution of three media effects models. Journal of Communication; 57(1): 9-20.

- Gil de Ziga H., Jung N., & Valenzuela S. (2012). Social media use for news and individuals’ social capital, civic engagement and political participation. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication; 17(3): 319-336.

- Yesayan T. (2014). Social networking: A guide to strengthening civil society through social media. Arlington, VA. US Agency for International Development. Available at: https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1866/SMGuide4CSO.pdf. Last accessed October 6, 2015.

- Doherty D. & Adler E.S. (2014). The Persuasive Effects of Partisan Campaign Mailers. Political Research Quarterly; 67(3): 562 – 573.

- Doherty D. & Adler E.S. (2014). Campaign mailers can affect voter attitudes, but the effects are strongest early in the campaign and fade rapidly. LSE US Centre. Available at: http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/usappblog/2014/09/10/campaign-mailers-can-affect-voter-attitudes-but-the-effects-are-strongest-early-in-the-campaign-and-fade-rapidly/. Last accessed December 21, 2015.

- Kurtzleben D. (2015). 2016 Campaigns Will Spend $4.4 Billion On TV Ads, But Why? NPR. Available at: http://www.npr.org/sections/itsallpolitics/2015/08/19/432759311/2016-campaign-tv-ad-spending. Last accessed October 20, 2015.

- Dingfelder S. (April 2012). The science of political advertising. Monitor on Psychology. Available at: http://www.apa.org/monitor/2012/04/advertising.aspx. Last accessed October 20, 2015.

- Parker A., Kantroo V., Lee H.R., Osornio M., Sharma M., & Grinter R. (2012). Health promotion as activism: building community capacity to effect social change. In: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM; 2012. p. 99-108.

- Berkeley vs. Big Soda. Available at: http://www.berkeleyvsbigsoda.com/. Last accessed October 20, 2015.

- Berkeley vs. Big Soda. (2014). Confused about Measure D? Don’t be. Campaign mailer. Berkeley: Berkeley vs. Big Soda.

- Berkeley vs. Big Soda. (2014). The Secret Playbook of Big Soda. Campaign mailer. Berkeley: Berkeley vs. Big Soda.

- Choose Health SF. (2014, March 19). ChooseHealthSF. [Tweet]. Available at: https://twitter.com/ChooseHealthSF/status/446442118769176576. Last accessed December 21, 2015.

- Berkeley vs. Big Soda. (2014, July 28). BerkvsBigSoda. [Tweet]. Available at: https://twitter.com/BerkvsBigSoda/status/493888650896490496. Last accessed December 22, 2015.

- Berkeley vs. Big Soda. (2014). 1 in 3 kids will get diabetes in their lifetimes unless we do something about it. Campaign mailer. Berkeley: Berkeley vs. Big Soda.

- Choose Health SF. (2014, July 22). [Facebook status update]. Available at: https://www.facebook.com/ChooseHealthSF/posts/274420936086418. Last accessed December 22, 2015.

- Nixon L., Mejia P., Cheyne A., & Dorfman L. (2015). Big Soda’s long shadow: news coverage of local proposals to tax sugar-sweetened beverages in Richmond, El Monte and Telluride. Critical Public Health; 25(3): 333-347.

- No Berkeley Beverage Tax. (2014, August 30). [Facebook post]. Available at: https://www.facebook.com/NoBerkeleyBeverageTax/photos/a.619135404868499.1073741829.603111666470873/620187211429985/?type=3. Last accessed December 22, 2015.

- No on D. Measure D is not what it seems. (2014). Campaign mailer. Berkeley: No on D.

- No Berkeley Beverage Tax. Available at: http://noberkeleybeveragetax.com/. Last accessed October 20, 2015.

- No SF Beverage Taxes. (2014, September 16). NoSFBevTax. [Tweet]. Available at: https://twitter.com/NoSFBevTax/status/511964096087228416. Last accessed December 22, 2015.

- No on E: Stop unfair beverage taxes. Available at: http://www.affordablesf.com/media/. Last accessed October 30.

- Berkeley vs. Big Soda. (2014, November 19). [Facebook status update]. Available at: https://www.facebook.com/berkeleyvsbigsoda/?fref=nf. Last accessed December 22, 2015.

- Mejia P., Nixon L., Cheyne A., Dorfman L., & Quintero F. (2014). Issue 21: Two communities, two debates: News coverage of soda tax proposals in Richmond and El Monte. Berkeley, CA. Berkeley Media Studies Group. Available at: https://www.bmsg.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/bmsg_issue21_sodataxnews1.pdf. Last accessed August 28, 2014.

- Torres F.A. (2014). La agridulce batalla de la Proposicin E. El Mensajero.

- Stepanski K. (2014). Remove your soda tax goggles: Berkeley is not Mike Bloomberg’s sugar baby. The Berkeley Daily Planet. Available at: http://berkeleydailyplanet.com/issue/2014-10-31/article/42642. Last accessed October 13.

- Woldow D. (2014, February 18). Truth an Early Casualty in SF’s Soda Tax Fight. Beyond Chron.

- The Ecology Center. (2014). Walk and talk for Measure D, Berkeley soda tax. Available at: http://ecologycenter.org/blog/walk-and-talk-for-measure-d-berkeleys-soda-tax/. Last accessed December 21, 2015.

- Colliver V. (2014, February 2). 2 plans to tax sodas, other sweet drinks merge for vote. The San Francisco Chronicle.

- Saunders D. (2013). Slim down the obesity problem. The Lawton Constitution.

- Associated Press. (2014, November 29). Soda tax loses its fizz. Providence Journal.

- Colliver V. (2014, February 2). United front in S.F.’s war on sodas, other sweet drinks. SFGate.

- Associated Press. (2014, July 23). San Francisco to vote on tax in November. USA Today. Available at: http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation-now/2014/07/23/san-francisco-soda-tax/13032045/. Last accessed October 9, 2015.

- States News Service. (2014). San Francisco, Berkeley voters to decide on soda tax. States News Service.

- Kaplan A. (2014). Don’t tread on me: The Berkeley soda tax may not be the turning point some industry opponents are making it out to be. Beverage World. Available at: http://www.beverageworld.com/blog/entry/25535/dont-tread-on-me. Last accessed October 9, 2015.

- Foster P. (2014). American Way: It is time to curb the great American sugar rush. The Sunday Telegraph. Available at: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/northamerica/usa/11233057/American-Way-It-is-time-to-curb-the-great-American-sugar-rush.html. Last ccessed October 9, 2015.

- Associated Press. (2014). California city becomes first to vote for tax on sugar-sweetened beverages. Progressive Media – Company News.

- Tugend A. (2002). Cigarette Makers Take Anti-Smoking Ads Personally. The New York Times.

- Dorfman L. & Wallack L. (1993). Advertising health: the case for counter-ads. Public Health Reports; 6(108): 716 – 726.

- Somji A., Bateman C., Nixon L., Arbatman L., Aziz A., & Dorfman L. (2016). Soda tax debates: A case study of Berkeley vs. Big Soda’s social media campaign. Berkeley, CA. Berkeley Media Studies Group. Available at: /publications/soda-tax-debates-a-case-study-of-berkeley-vs-big-sodas-social-media-campaign/. Last accessed January 28, 2015.

- Coalition for an Affordable City. Available at: http://www.affordablesf.com/. Last accessed October 20, 2015.