Housing, equity, and health in U.S. news, 2020-2021: Findings and recommendations

Wednesday, July 06, 2022Introduction

The evidence is clear: Health depends on access to safe, stable housing.1–5 Unfortunately, a legacy of inequitable and unjust housing policies limit access to housing for many people, based on factors like race, immigration status, disability status, income-level, gender, and sexuality. These systemic barriers to having a quality, affordable home are key drivers of health inequities in the United States. As such, helping the public and policymakers understand the connection between housing and health is a key step toward not only advancing housing policy and improving community health but also toward strengthening the movement for racial and health equity.

Is the impact of housing on health clear to the public and lawmakers? We can look to the media to find out. News coverage provides insight into the public discourse about housing, as well as into opportunities for and potential barriers to shifting that discussion. All forms of media — print, broadcast, and social — significantly influence the public’s and policymakers’ knowledge of many issues, including housing.6–8 Journalists and editors often set the agenda for the public debate about a topic by deciding which details they report (or don’t report) and how they frame their stories. News coverage, then, offers a window into understanding whether and how people think about housing. Is it on their radars? If so, what do they know about the problem? What they think should be done?

Framing refers to how an issue is portrayed and understood. Frames shape the parameters of public debates by promoting particular definitions of a problem, its causes, its moral aspects, and its possible solutions.9–11 Many factors influence what frames get evoked in news stories: the language that’s used, what types of information are highlighted, the potential solutions that are discussed, and whose perspectives are included or left out. Frames that are repeated often and deeply ingrained become the housing narratives that either confine our policy choices or make a vision of housing justice possible.

Understanding how journalists currently frame housing, and how those choices shape long-term narratives, can help housing and health advocates be strategic about their communication strategies. For example, a framing analysis of the news can inform advocates as they decide what messages to use to win immediate policy goals, while also shaping local and national narratives to portray housing as a social good that supports individual and community health.

To understand the specific nuances of how news coverage frames the complex intersections of housing and health equity, Berkeley Media Studies Group (BMSG) conducted an ethnographic content analysis12 of news about housing and health equity from media markets across the country, informed by feedback from grantees funded by the Kresge Foundation’s Advancing Health Equity Through Housing Initiative working in those communities. Here, we present a summary of findings, as well as recommendations that we hope will help grantees and other advocates working to emphasize the nuanced connections between housing and health and elevate just and equitable approaches to ensure stable housing and good health for everyone.

What we did

To build on quantitative news analyses BMSG conducted in 2021, we analyzed the content of print news stories about housing and health from across the country. To identify which stories to analyze, BMSG researchers first developed a search string (targeted words used to pull articles from large databases) to collect news about a range of housing issues. The search string was informed by responses to a questionnaire that was sent to Health Equity and Housing (HEH) grantees working in 22 different locations around the country. To capture news about housing, the final search string included terms related to grantees’ diverse focus areas and policy strategies that center racial and health equity, including affordable housing, tenant protections, homelessness, and community land trusts, as well as equity and health-related terms, such as “low-income,” “disparities,” “equity,” and others.

Using LexisNexis and ProQuest, BMSG identified and collected print and online news articles published between June 1, 2020 and May 31, 2021 in 22 outlets that represented grantee media markets (see Appendix A for a full list of outlets and media markets sampled). For each of the four outlets in the sample that included both national or regional and local coverage (such as The New York Times or the Los Angeles Times), we added location terms like “New York City” or “Los Angeles” to narrow the search to local news.

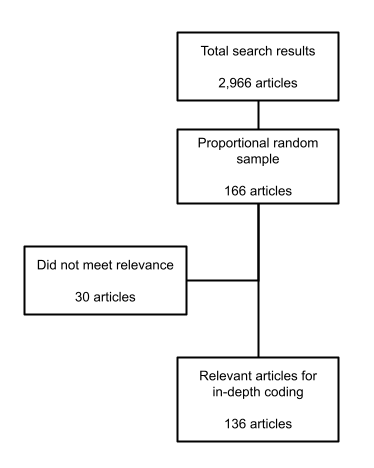

We found 4,349 articles published between June 1, 2020 and May 31, 2021 that met our search criteria. We used proportional random sampling to build a representative sample of 166 articles. We then removed 30 articles that did not substantively discuss housing issues in the United States (see Figure 1): For example, we excluded a story about a crime that happened to involve a recently evicted tenant13 and articles about housing issues outside of the United States. Our final generalizable sample included 136 relevant articles from around the country.

To code relevant articles, we drew on our synthesis of communication research about housing, as well as our own previous studies of housing in the news,14,15 feedback from Kresge’s housing and health team, and insights from HEH grantees. We developed a robust guide to help coders identify and capture persistent themes in the coverage.

The final codebook addressed questions like:

- What kinds of topics related to housing appear in news coverage?

- Do articles about housing and health equity discuss root causes of housing instability, insecurity, inequity, or homelessness, and the consequences for individuals, families, and communities?

- Who speaks in the news about housing and health equity? Whose voices are missing?

- Who is called upon to take action to address housing issues, or is portrayed as being responsible for the cause of housing issues and the solutions?

- Do solutions to housing instability or homelessness appear? If so, which ones are named?

- How is the COVID-19 pandemic framed in news about housing and health equity?

- Do articles about housing and health equity explicitly address racial equity? If so, how?

Before coding the full sample, we used an iterative process to refine the codebook guide. We then conducted multiple rounds of intercoder reliability testing and a statistical test to achieve consensus among coders to ensure that coder agreement did not occur by chance; we achieved satisfactory reliability measures for each coding variable (Krippendorff’s alpha >.816).

What we found

We first present overall findings about article types and topics, followed by a summary of how equity and health were framed in the stories. Finally, we describe the key “characters” who appeared in many stories about housing, equity, and health, and other features of the coverage relevant for housing advocates.

What’s the story about housing? Overall findings

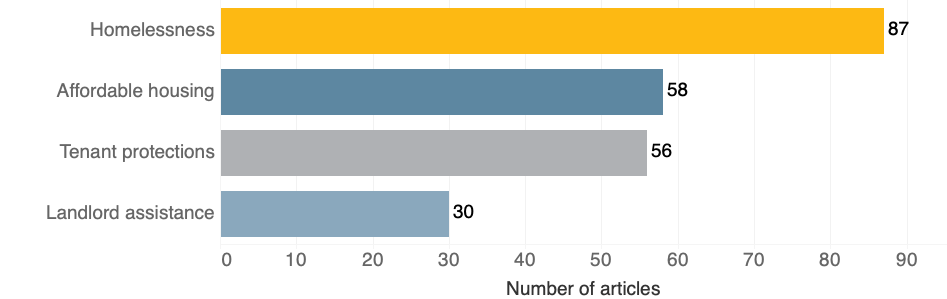

Across the nation, the majority of articles about housing, equity, and health focused on homelessness (see Figure 2), though affordable housing and tenant protections also generated coverage and, in some media markets, generated more news than homelessness (see the quantitative news analysis for highlights from each of the 22 jurisdictions). While our search string did not explicitly include terms related to assistance for landlords, over one-fifth of articles (22%) mentioned protections for landlords, including mortgage support and conflict mediation programs with tenants, which an article from The Philadelphia Inquirer described as ”a program that would benefit landlords by providing access to resources.”17

Figure 2: Housing issues in news coverage.

News peaked in December 2020 with stories about the expiration (and subsequent extension) of eviction moratoriums related to COVID-19. Coverage spiked again in April 2021, when President Biden announced the American Rescue Plan, which included grants for addressing homelessness and financial assistance for tenants and renters to compensate their landlords. We wanted to know: When housing and health appeared together in the news, why? Why that story, and why that day? Reporters commonly refer to the catalyst for a story as a “news hook,” and many factors can influence why reporters and editors select some stories and not others.

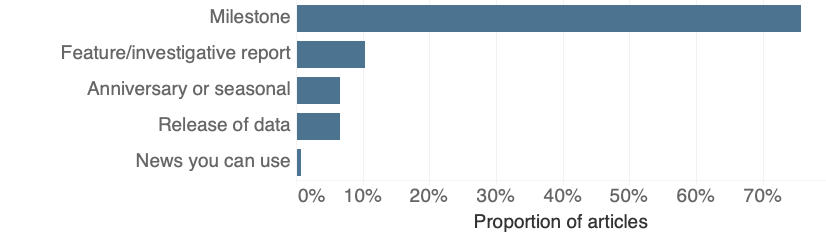

For each article we answered the question, “Why was this story published today?” We found that over half were in the news because of a milestone or breakthrough achieved in a policy, initiative, or program (see Figure 3): A typical article from The New Orleans Advocate, for example, hinged on the announcement of federal grants to support subsidized housing in the city.18 At times, the milestones that drove coverage were controversies that generated fierce debate, like the unveiling of an affordable housing plan that triggered a battle between affluent and working class neighbors in Dallas19; the release of a statement warning about the possibility of an eviction crisis in Annapolis20; or a review of a debate over closing shelters for people experiencing homelessness during the pandemic in Philadelphia.21

Figure 3: News hooks in final sample (n = 136 articles)

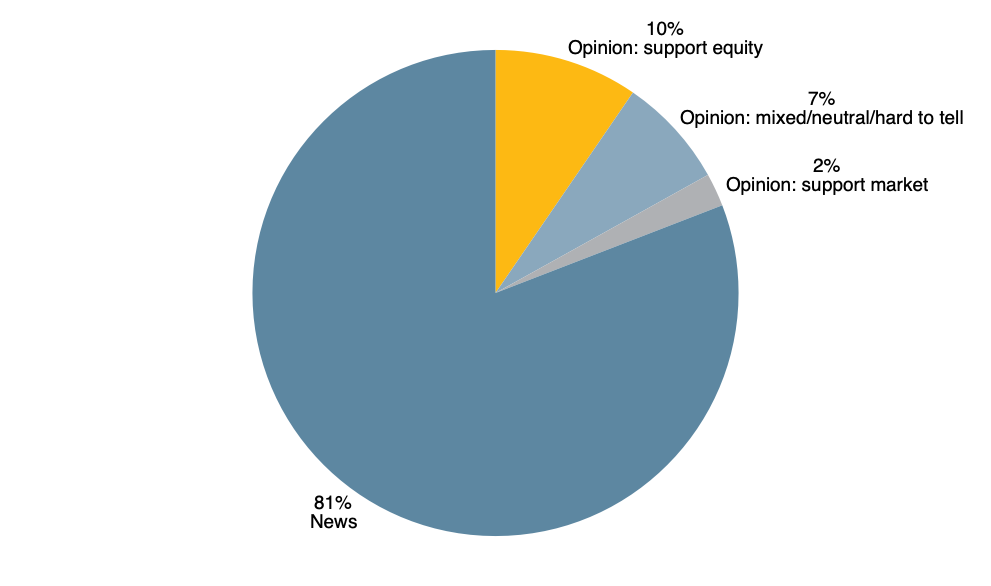

Although most articles were news articles (see Figure 4), almost one-fifth of stories (19%) about housing and health equity were opinion pieces, like editorials, op-eds, or letters to the editor. Half of all opinion pieces contained language or framing that in some way named equity issues (13 articles, or 10% of the full sample), as when, for example, opinion authors in The Washington Post called for “additional attention to addressing the root causes of eviction” and named the need for “strengthening emergency rental assistance programs and housing subsidies for eligible families [to] bring attention to the systematic problems of housing affordability.”22 By contrast, other opinion pieces (7% of the sample) focused instead on financial impacts on developers, as when one resident in a letter to the editor stated, “The overwhelming obstacle blocking the path to more affordable housing construction in Los Angeles is that the numbers just don’t work. … Private developers cannot make a profit on low-income housing.”23

Figure 4: Coverage type of articles in final sample (n=136 articles)

What’s in the frame? Health, equity, and COVID in housing news

Our search string was designed to capture housing articles that referenced health, equity, or equity and health together. Since our analysis encompasses news published during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is not surprising that most articles about housing (71% of all articles) focused on the global health crisis. One article quoted the governor of Virginia, who lauded a decision to suspend evictions for nonpayment of rent because “we are still battling this public health crisis and need all Virginians to maintain safe, stable housing.”24

Many articles that mentioned the pandemic described the connections between housing and stopping the spread of the virus, though some went beyond virus containment to address other health consequences associated with housing instability. In an interview with the Orange County Register, for example, a housing researcher described the impact of pandemic-related evictions on children’s health, saying, “Housing stability is critical for kids’ well-being, everything from educational outcomes to health outcomes.”25

Most articles about COVID (82%) included language that framed the pandemic as exacerbating existing housing issues. One Trenton-based housing advocate, for example, observed that many of his clients “were struggling even before COVID to make the [rent] payment.”26 A feature in The New York Times, meanwhile, included remarks from an academic who observed, ”What these two crises have laid bare is that this extraordinarily wealthy city … was completely failing other segments of the population,” and then wondered, ”How can we use this pause to think about the city that should be — a more equitable city?”27

Nearly two-thirds of stories that mentioned equity, and specifically racial equity, were problem-focused — that is, they named racial disparities, including the disproportionate impacts of housing insecurity and homelessness, especially among Black, Indigenous, people of color, immigrants, and low-income communities. Several articles described the root causes of inequities: One op-ed by a Long Beach City Council member, for example, pointed out that “many of our communities were designed at a time when federal and state policy explicitly called for the separation of people by race” and concluded, “The average cost of owning a home in predominately white neighborhoods is nearly two times more than non-white communities.”28

Similarly, a story about a report on environmental contamination named environmental racism and noted that “laws and policies have put Black and Brown communities in direct proximity to environmental toxins.”29 Only one-fifth of articles that mentioned equity focused on solutions: A rare article from the Detroit Free Press sought to expand readers’ understanding of the Fair Housing Act of 1968 and its goals of “stopping discrimination in housing … [and promoting] a diverse society, in this instance, a racially diverse community.”30

Occasionally, the news elevated the connections between housing, equity, and health. Most stories that connected the three issues were opinion pieces that focused on evidence of inequity and disparities in housing and health: For example, an op-ed by two Boston physicians warned that “homelessness and housing instability not only fuel the high rates of COVID-19 infections, especially in Black, Latinx, and immigrant communities, but also accelerate chronic illnesses and lead to higher rates of all causes of mortality.” The article concluded that, “successful models of stable, affordable housing save lives and ultimately drive down overall medical costs.”31

In Philadelphia, two faith leaders penned an op-ed arguing for renter protections, noting that “a wave of homelessness will undoubtedly incite a second spike of COVID-19 cases, overtaking our poorest, most vulnerable neighborhoods, and compounding the racial disparities that have become increasingly glaring.”32

Who’s in the frame? “Characters” in the news about housing, equity, and health

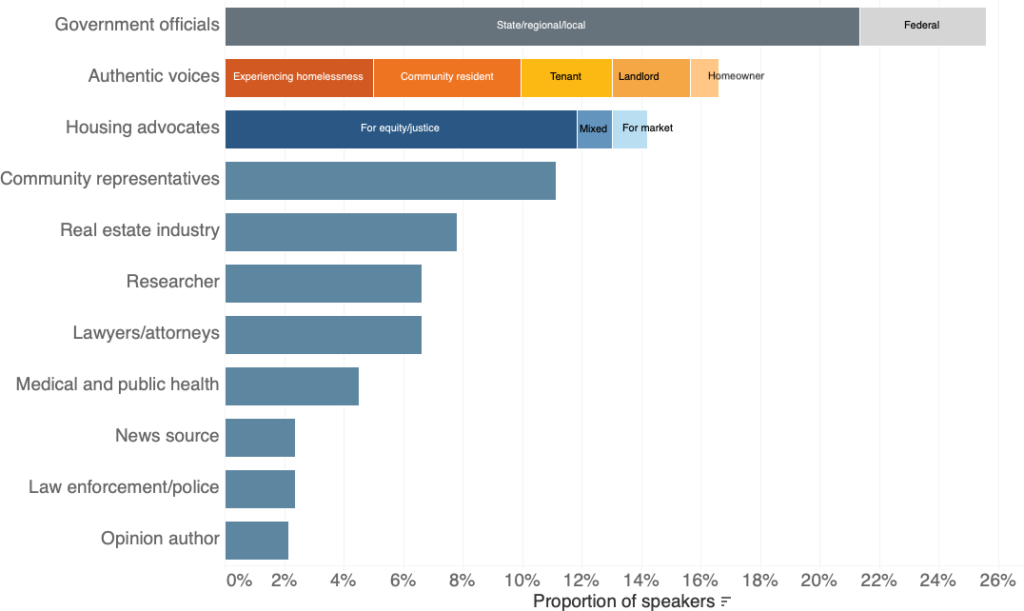

To understand whose perspectives and stances are elevated in the news and whose are obscured, we determined which speakers were quoted or discussed in the news about housing, equity, and health, as well what they said (or what was said about them). Overall, we found that government officials, most representing city or state government, were most frequently quoted, and accounted for 25% of speakers in the news (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Speakers quoted in articles about housing, equity, and health (n=136)

Authentic voices — people who can speak about an issue from the unique vantage point of their own lived experience — accounted for almost one fifth of news speakers (17%). These sources, such as people experiencing homelessness, tenants, and landlords, included both those who support and those who oppose housing policies that promote equity and justice. Representatives of community organizations (like churches and schools) made up 11% of speakers, while just 5% of speakers were medical or public health professionals, like a Los Angeles doctor who discussed her experience providing “street medicine” to unhoused people.33

People who identified as housing advocates made up 14% of speakers. Housing is a complicated and multifaceted issue, and housing advocates are not a homogenous group, so it’s not surprising that an equity focus is not always central to housing advocacy work. Specific players may at times be aligned and at times in opposition. For example, coalition members who work together to advance affordable housing projects may not align when it comes to tenant justice work that centers racial equity. To help make sense of the diversity of perspectives around housing, Figure 6 represents a simplified assessment of the perspectives of three groups involved in shaping housing policy and news coverage of these policies. This chart is based on BMSG’s work with housing and health justice advocates from around the country.

Figure 6: A range of perspectives on housing activism and advocacy

| NIMBY (“Not In My Backyard”) | YIMBY (“Yes In My Backyard”) | Housing Justice |

| Housing as a commodity | Housing as a commodity | Housing as a social good |

| Support limiting supply/development of new housing in certain areas | Support development of new housing | Support equitable access to affordable housing |

| Protect value of property and personal wealth | Protect corporate interests and profits | Protect human rights |

| Individual responsibility and solutions (bootstrapping) | Market responsibility and solutions (supply and demand) | State responsibility and solutions (safety net) |

| Exclusion | Limited inclusion | Inclusion |

Of the various types of speakers, many of the housing advocates who appeared in news coverage explicitly spoke about housing justice and racial equity. One Boston-area advocate pointed out that a coming eviction crisis would “disproportionately impact communities of color,”34 while a representative from the Los Angeles-based Enterprise Community Partners, concluded that “low-income neighborhoods of color will need a lot more aid to prevent further gentrification and economic devastation.”35 Across the board, speakers were quoted using technical terms or jargon like “linkage restrictions,”36 or “safe sleep zones,”37 or contained poorly defined terms or ambiguous phrases like “affordable housing” or “housing provider” (16% of articles).

Journalists may not use these terms, but the themes we see in our news analysis often parallel the narrative techniques that are deeply ingrained in fiction writing, with conflict, setting, characters, point of view, and other common story elements. Below we explore how several key “characters” appeared in the coverage:

Government actors are called upon to address housing problems.

We know from decades of media research that news about many issues commonly focuses on problems, rather than on solutions.38 The news about housing, equity, and health is unique in that many stories (96%) named a specific solution to at least one housing issue like homelessness or lack of affordable housing. Many solutions centered on government action like increases in funding (39% of all references to solutions) or changes to state, local, or federal housing policy (34% of references to solutions). An op-ed from The Boston Globe, for example, called for “$30 billion for national housing rent and mortgage assistance,”31 and an article from the Los Angeles Times addressed the debate over a series of state-level policies designed to protect renters as part of a “sweeping economic recovery effort” in California.39

We also documented all explicit calls to act on housing issues and found that responsibility was regularly laid at the feet of local, state, or federal government entities (80% of all assertions of responsibility). A typical article from The Arizona Republic called on “state lawmakers [to] take action to restore the state investment to the housing trust fund and enact new tools like a state affordable housing tax.”40 Similarly, an op-ed from The Philadelphia Inquirer urged “the members of City Council to rally behind [legislation to protect renters] as a first step in rebuilding the fabric of our beautiful city.”32

When government entities failed to act on housing, they were sometimes swiftly taken to task, as when a YIMBY housing advocate (see Figure 6) sternly rebuked the California Legislature for “its refusal to pass a housing production package that addresses the depths of the housing shortage,” saying that it “failed the people of California.”39 A Minneapolis resident, meanwhile, denounced city and state government as being “either indifferent or incapable of finding a long-term solution,” and concluded “a turn to the private sector is necessary.”41

Landlords and tenants are portrayed at odds.

The news regularly framed tenants and landlords as being against one another and boiled the complexities of housing policy down to a “he said-she-said” format. Reporters often portrayed landlords as struggling due to unreasonable or untrustworthy tenants: For example, the head of an organization representing California landlords argued that pandemic protections should be subject to means-testing because of his organization’s assertion that “there are some [tenants] who have taken advantage”42 of the laws. Similarly, an article from Atlanta highlighted the remarks of a judge who warned tenants that COVID-related financial hardship, while a “legitimate reason for not paying rent,” is “no fault of the landlord,”43 even as rent relief legislation went to landlords and helped them as well.

Other articles framed landlords as reasonable and fair actors fighting unreasonable policies that prioritize tenants. One Los Angeles Times article quoted the head of the California Rental Housing Association, who acknowledged that “renters that have been adversely affected by COVID-19” but concluded that policies extending eviction moratoriums would “lead to more harm throughout the rental housing industry and California’s economy.”44 Such “scarcity framing,” which reinforces the idea that when one group benefits another must lose,45 was common in articles that pitted landlords against tenants. By contrast, we seldom saw stories that framed policies to expand housing resources as a win for all. A rare example came from an article in which a representative speaking for Washington state landlords described legislation to provide legal counsel for tenants as “[providing] value to tenants and to landlords because it helps to resolve cases more quickly.”46

A number of articles framed landlords as unscrupulous and harmful to tenants as when one renter observed, “My landlord knows that the rental market is in his favor; he can behave in an egregious manner without serious repercussions.”47 An editorial from The Philadelphia Inquirer denounced landlords for “[filing] 20,000 evictions a year … despite the devastatingly long list of harms associated with eviction,”17 and a community advocate in Orange County worried that landlords would exploit rent relief laws to “pick and choose the fate of [a tenant’s] life and whether or not they’re going to be saddled with thousands of dollars of debt.”35

Unhoused people share personal stories that evoke pity and fear.

Though unhoused people accounted for 15% of speakers in the news (and were most often quoted in articles from The Seattle Times and The Philadelphia Inquirer), the news did not quote unhoused people speaking as experts on the issues facing their communities or tying their experiences to needed solutions. Instead, most unhoused people in the news told vivid personal stories about their own struggles. A typical story profiled an unhoused Oakland man who described “sleeping here and there, worried about catching coronavirus,”48 while an unhoused person in Los Angeles described struggles with addiction, saying, “It always felt to me like I’d fallen off a fire escape, and once you get on the ground, the ladder is 12 feet up in the air … I always thought, ‘If I could just get to that first step.’ But the first step is so far away.”33

When they were spoken about, unhoused people were sometimes described using language that evoked fear, distrust, and kept the frame squarely focused on deficits and problems. One LA resident who lived across from a shelter complained that she “can’t take her mother for a walk and sleeps with a baseball bat,” and concluded, “I’m scared.”49 Other stories about unhoused people evoked pity or helplessness: One adult unhoused Oakland resident, for example, was called “a sweet child” and a “victim of circumstance”48 by housing center staff, while Los Angeles Times columnist Steve Lopez described an unhoused woman as “barefoot, caked in dirt, may be pregnant and is often naked …” before declaring, “she is deteriorating before [neighbors’] eyes.50 Other depictions of unhoused people focused on their resilience, as in an article from Philadelphia that described an unhoused man as “stoic” in the face of an uncertain future.51

Housing justice advocates and community leaders pull back the lens on inequities and local needs.

Housing justice advocates and community leaders often appeared in the news to provide important context in stories about housing, equity, and health. Many of the most overt statements about structural and systemic inequities came from housing advocates. In Seattle, for example, leaders from community group Equity Now denounced city leadership, arguing, “In a society that does not allow for upward social or economic mobility, our city refuses to provide the services and/or resources necessary for … clean, safe and stable housing, adequate food and sustenance, and security for all of its residents.”52 In St. Paul, Minnesota, meanwhile, a representative of the Rondo Community Land Trust pointed out that “the [housing] market continues to go up and incomes have not kept up for the families that we serve.”53

Community leaders representing many different local organizations (including churches, neighborhood coalitions, and community centers) provided details and reactions that help illustrate the nuances and limitations of solutions to housing problems. For example, John Maceri, executive director of a nonprofit social service agency, expressed doubts about an initiative to rent hotel and motel rooms for temporary shelter, observing, “I don’t think it’s going to be anywhere near what’s going to be needed to fill in the gap.”54 Similarly, the director of a neighborhood center in Miami described the logistical challenges facing residents seeking public housing support, expressing concern that “people who most need Section 8 won’t get help navigating the application process — or will get left behind because they don’t have internet access.”55

Bringing it all together

Our analysis of news about housing, equity, and health revealed that during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, coverage explicitly connected housing to COVID-19. Most articles discussed the impact of the pandemic on existing disparities or called for changes to address housing instability as a way of preventing the spread of the virus and supporting vulnerable communities in their efforts to recover from the pandemic. Few stories connected housing to any other health outcome besides COVID.

Various characters, or sources, appeared in housing news against the backdrop of the pandemic, including landlords, tenants, unhoused people, and housing advocates. Many of these figures were framed in conflict with one another. The deepest divisions appeared between landlords and tenants, with both sides periodically accusing the other of duplicitous or unscrupulous behavior. This “he said-she said” format often flattens complex policy issues, their histories, and future impacts without the context that would help the public understand the need for equity-focused solutions and would hold policymakers accountable for enacting them.

Unhoused people were regularly quoted in the coverage, but most often only to share graphic details of their lived experience on the streets; rarely were they called upon to share their expertise about the housing crisis, or to advocate for solutions. Beyond engendering pity or fear, such narrow, individually focused stories potentially obscure the broader policy or historical landscape that could help readers understand why so many people are unhoused or set the stage for reporting on equity-focused solutions.

Government officials were also prominent figures in the coverage and were often called upon to address housing issues and rectify inequities: Indeed, most stories were in the news because of a milestone or breakthrough achieved in a policy, initiative, or program. News about housing is unusual in this respect because previous analyses of news about a number of issues have documented that coverage seldom evokes the role of government in solving problems. This pattern in coverage likely stems from the well-documented tension in the United States between the notion that health and well-being are shaped purely by personal choices and the belief that institutions, including government entities, also must act to protect the public’s health.38,56

When racial justice and the relationship to housing and health equity were covered, reporters focused on disparate impacts or troubling data points, rather than describing solutions or quoting sources who could describe their vision for what housing and health could look like in their communities. Black, Indigenous, and other people of color were most often mentioned in statistics documenting inequities.

Recommendations for those working toward health equity and housing justice

Our analysis of the news, an important part of our public discourse, reveals several ways advocates and practitioners working around the country could elevate the connections between housing, equity, and health in their public statements. With an eye toward filling those gaps, we present recommendations to aid advocates in improving news coverage on housing and building a new narrative that shines a light on the deep connections between housing, equity, and health to support policies that can ensure stable housing and good health for everyone.

Bring racial equity into the frame.

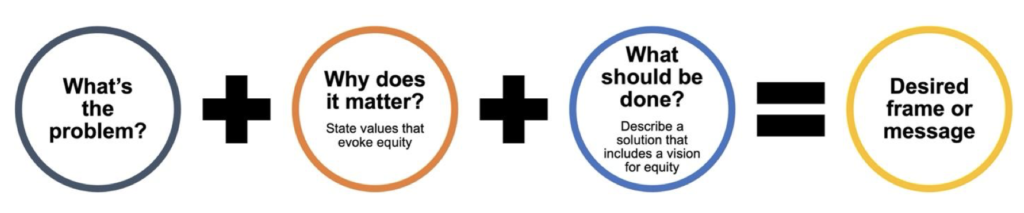

Every message is an opportunity to bring racial equity into the story. From social media to speaking to a reporter, a simple, tested message strategy is to include compelling values, a clear solution, and a very brief description of the problem (since news coverage often focuses more on the problem).

Action 1: Frame racial equity as part of the solution, not just the problem.

Reporters most often bring racial inequities into their stories when they describe housing problems using data, statistics, or stories of individuals who are suffering. Racial equity as a guiding vision for how housing policies can transform our communities appears less often; especially missing are descriptions of how innovative solutions that center communities of color also will benefit broader communities, cities, counties, and states. This means advocates need to explain not just what led to this dire situation, but also the outcomes they expect to see when equity-focused policies are adopted and enforced.

Action 2: Uplift Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) as leaders and experts.

News coverage of housing inequities often conveys how BIPOC communities have been harmed but less often describes the actions BIPOC communities are taking to proactively address housing issues. One way advocates can be sure racial equity is depicted as part of our vision for the future is by elevating BIPOC leadership (including youth leaders, people with disabilities, people who are unhoused, people who are immigrants, people who have been incarcerated, and more) as experts in news coverage of housing issues. There is ample opportunity for BIPOC leaders to be portrayed as policy experts, data and trend experts, or as advocates who are creating solutions that will reduce inequities and benefit the health of the city, county, region, or state. Showing how BIPOC leaders and organizations are successfully advocating for equity-focused housing solutions will demonstrate the range of assets these leaders bring that can benefit their community and beyond.57

Related resources

In addition to bringing racial equity into the solution, advocates can tie racial equity to values in messages. Many recent housing narrative resources that incorporate racial equity are designed to help advocates be explicit about racial equity, build long-term narratives around it, and win:

- In the book The Sum of Us: What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together, Heather McGhee draws on the value of interconnectedness and provides numerous examples of how addressing structural racism can improve prosperity for all.

- The Race-Class Narrative Project provides research and examples that illustrate how the value of unity has been powerful in many different contexts and across various issues, including housing.

- Community Change, Race Forward, and PolicyLink also provide materials that center racial equity in housing narratives.

- BMSG has several resources that can help advocates connect narratives on racial equity to concrete action steps.

Connect housing to health in the context of COVID — and beyond.

We found that many reporters did explain that COVID exacerbated racial and health inequities, but as COVID coverage wanes, it is likely that reporters will go back to more siloed reporting that isolates housing in one beat and health in another. As advocates develop media and messaging strategies, they should ask themselves: How are we setting ourselves up to communicate about housing and health post-COVID?

Action 1: Illustrate that long before COVID, decades of problematic housing policies exacerbated health disparities.

When advocates are intentional about connecting health and housing, and bring in a racial equity lens, they can shape news coverage so decision-makers understand why equity-focused solutions are needed, as well as the rationale and values motivating advocates’ solutions. Advocates should have ready examples of how unstable housing can harm health, how health improves when housing is stable, and how those benefits accrue to the broader community when all residents have a safe and secure place to call home.

Action 2: Demonstrate the connections among equity, housing, and health.

If advocates build coalitions to organize and connect equity, health, and housing, it will be easier to connect the dots for journalists when delivering messages.

For example, if journalists are covering federal policy related to housing decisions, a public health practitioner could pitch a local story about community-led efforts to strengthen local tenant protections for those impacted by COVID —a story that will be much easier to pitch if health practitioners and housing advocates are already working together in coalition.

Position the story “characters” to broaden the frame about housing.

Op-eds and other opinion pieces are one place where language about equity, including racial equity, and health appeared in the news. Of course, a single news article or op-ed will not create massive shifts in how we view housing in our society. However, when characters, or sources, who represent and speak to equity-focused values and solutions appear across multiple news stories, their portrayals combine to help build a new, longer-term housing narrative that also advances shorter-term campaigns or policy actions.

Action 1: Cultivate messengers across diverse sectors.

When public health messengers are missing from the news, it is harder to frame housing as a health issue — a promising narrative for generating policy support.58 Enlisting people from public health and other non-housing sectors to speak with reporters can make the connections between issues tangible, and show how working across sectors can attract a bigger base of supporters.

For example, if journalists are covering federal policy related to housing decisions, a public health practitioner could pitch a local story about community-led efforts to strengthen local tenant protections for those impacted by COVID.

Action 2: Cultivate messengers across diverse communities.

Diverse messengers can shift the narrative about power: When those who have been most harmed by historical and current housing policies are quoted in news stories, they can demonstrate that they have agency and can lead us to a better future. In addition, when people facing housing instability share their own stories in ways that connect to solutions, data, trends, and policy, their news “character” expands beyond “victim”: They become people with agency and power. Advocates should prioritize expanding the range of BIPOC leaders who are at the forefront of imagining and working toward a vision for housing justice so reporters will have an abundance of sources who can expand the frame in their stories.

Action 3: Prepare messengers to be clear and effective in high-stakes situations with reporters.

Speakers need support. That means providing them with the training and resources they need to be confident and comfortable when speaking with journalists. Organizations can work with all their messengers to provide training and coaching so they are prepared to answer hard questions with the courage of their conviction.

Possible training topics for messengers could include media advocacy training on how to tie strategy to communication; help with using precise language and avoiding jargon so anyone reading or viewing the news is able to understand their words; creating news that highlights community action and expertise; and writing and pitching op-eds.

Expand the frame around the role of government.

The news about housing is unique in that government actors regularly appear and are called upon to act in stories about housing, equity, and health — far more so than in news about other issues we have studied. That’s not surprising, since many of the solutions housing and health justice advocates seek are related to government action.

Often, government actors are evoked in the news in the context of valid critiques of how they or the agencies they represent are falling short. This presents a communication challenge, however, because the agencies and entities being critiqued are often necessary parts of addressing inequities and ensuring safe, stable housing for everyone. If the narrative about housing frames government only as inept, bumbling bureaucracy, it may be harder for audiences to see and believe that government must also be part of the solution.

If advocates are proposing any role for government actors or agencies in their solutions, then they need to convey that the agency can get the job done. That doesn’t mean avoiding criticism; instead, advocates should connect their critiques to actions the government must take, use critiques as a space to hold government actors and agencies accountable for racial equity, and insist on proper government action in the long-term.

Action 1: Be specific about which government actors and agencies must act — and what they should do.

One way advocates can both critique government and still include it as part of the solution is to name the specific government actors engaged in housing policy they are working to change. This might include people from local, state, and federal government; elected officials; administrative agencies; public health departments; housing agencies; and those administering government grants that reach community-based organizations. It is not necessary to describe every nuance of the housing landscape and its players in every conversation with reporters. Instead, advocates can be concise and specific about what they want a particular government actor or agency to do in this instance.

Action 2: Hold government accountable for racial equity in housing solutions, even when it’s difficult.

Polling shows that people are increasingly aware there is a housing crisis and are more open to government being part of the solution.58 In other words, now is a good moment to use the news media to remind leaders that the solutions they propose must support everyone in our communities, and that the public wants them to act.

Action 3: Tie housing solutions to your long-term vision for change.

Housing policy is extremely complicated, with multiple layers and solutions. As a result, housing inequities and the ongoing housing crises can appear hopeless, and it’s hard to build public support for changing issues that seem intractable and overwhelming. Advocates must show examples of success and explicitly make the connection between immediate policies and campaigns and a long-term vision of an inclusive housing landscape that provides homes for all.

Before an advocate speaks to a reporter, they should ask themselves questions like: How can I show that my solution is the right one? Am I talking about my policy goal in a way that is just about getting the next policy passed? Or am I talking about it in a way that helps us rethink housing, homes, and health?

Recommendations for journalists

The news analysis revealed reporting gaps that, if addressed, could provide a fuller picture of housing and its relationship to equity and health. The following recommendations for reporters are designed to expand and deepen news coverage so that the public and policymakers will have a more complete picture of what could be done to bring a close to our nation’s housing crisis.

- Avoid using language that personifies the housing market. Doing so obscures the role of decision-makers, making it harder to hold them accountable and narrowing the range of possible solutions. Instead of describing the market as a natural force acting of its own volition (for example, by saying, “the housing market did …”), reporters can explain how policy decisions shape the market; they can name where the action originated by saying what elected officials, landlord or developer lobbies, advocates, or others decided to do.

- Expand who is considered an expert source. In many news articles, when reporters refer to trends or data to diagnose current problems or predict the future, they turn to the real estate lobby, think tanks, and other “experts” who provide specific indicators based on their own interests. Reporters could ask those most impacted by the housing crisis about their diagnosis of the problem and the solutions they favor. This fresh approach can also help journalists move away from “he said-she said” storytelling that focuses on interpersonal conflict between, for example, landlords and tenants.

- Address the long-term impact of immediate policy actions. Most stories about housing and health were in the news because of an action in the policy process. Consequently, despite their length and complexity, many articles about housing focused only on the policy details of short-term, transactional solutions disconnected from the long-term impact of those solutions. Reporters can ask their sources questions about the long-term vision of their work that will help them, even briefly, connect the larger, housing-related issues — those concerning health, equity, and community well-being —with the policy moment or action currently in the spotlight.

Closing thoughts

Recent polling shows that more people are acknowledging that we must collectively address the national housing crisis, even if they are uncertain of solutions.58 Against that backdrop, this snapshot into national news about housing and health during COVID illustrates that there are promising areas of movement toward the goals of housing justice and racial and health equity in the U.S. For example, when they appear in the news, advocates can infuse stories with language about equity, government actors and actions are named, and articles about COVID make the link between housing and health visible, at least in terms of COVID outcomes.

The analysis also reveals opportunities to improve coverage and win concrete changes to improve people’s lives in terms of housing and health. Fortunately, we are in a moment when we know more about housing narratives than ever before. We can draw on both that research and real-world examples of advocates who are centering racial equity and winning. We can also look for guidance from leaders who are working to build movements and narratives across issues so that work on housing also uplifts efforts in many other sectors that are necessary to achieve true racial and health equity.58-64

Social change, especially amid a global pandemic, can be hard to see and even harder to measure. But housing and health advocates are raising their voices, getting their issues in the news, shifting conversations, and ultimately changing the housing conditions that can either support health or be a barrier to thriving communities. With continued investment and support to implement the narrative-change recommendations outlined here, as well as others from recent housing narrative research, advocates will be well poised to continue to build momentum and effect concrete change toward the goal of making homes and health a reality for all.

Acknowledgments

This report was written by Pamela Mejia, MS, MPH; Kim Garcia, MPH; Sarah Perez-Sanz, MPH; Katherine Schaff, DrPH; and Lori Dorfman, DrPH. Special thanks to Kim Garcia and Sarah Perez-Sanz for lending their data analysis expertise to this project. Additional thanks to Heather Gehlert for copy editing.

Many thanks to The Kresge Foundation for funding this project.

Appendix

| Kresge partner region | Outlet |

| Atlanta | Atlanta Journal Constitution |

| Baltimore | Baltimore Sun |

| Boston | Boston Globe |

| Buffalo | Buffalo News |

| Charlottesville | Staunton Daily News Leader (Note: No Charlottesville newspaper on Nexis) |

| Dallas | Dallas Morning News |

| Detroit | Detroit Free Press |

| Hartford | Hartford Courant |

| Honolulu | Honolulu Star Advertiser |

| Los Angeles | Los Angeles Times* |

| Miami | Miami Herald |

| Minneapolis | Star Tribune |

| New Orleans | Times Picayune/New Orleans Advocate |

| New York | New York Times* |

| Oakland | East Bay Times* |

| Philadelphia | Philadelphia Inquirer |

| Phoenix | The Arizona Republic |

| Santa Ana | Orange County Register |

| Seattle | Seattle Times |

| Trenton | The Times of Trenton |

| Washington, D.C. | The Washington Post* |

| Yakima | Tri-City Herald (Note: No results found for Yakima Herald) |

References

1. Downing H. The health effects of the foreclosure crisis and unaffordable housing: a systematic review and explanation of evidence. Soc Sci Med. 2016;162:88-96.

2. Cannuscio C, Alley D, Pagan J, et al. Housing strain, mortgage foreclosure, and health. Nurs Outlook. 2012;60(3):134-142.

3. Currie J, Tekin E. Is there a link between foreclosure and health? National Bureau of Economic Research. Published 2013. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.nber.org/papers/w17310

4. Phillips D, Clark R, Lee T, Desautels A. Rebuilding Neighborhoods, Restoring Health: A Report on the Impact of Foreclosures on Public Health. Causa Justa and Alameda County Public Health Department Accessed May 12, 2022. https://acphd-web-media.s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/media/data-reports/social-health-equity/docs/foreclose2.pdf

5. Braverman P, Dekker M, Egerter S, Sadegh-Nobari T, Pollack C. How Does Housing Affect Health? Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2011. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2011/05/housing-and-health.html

6. Gamson W. Talking Politics. Cambridge University Press; 1992.

7. Dearing JW, Rogers EM. Agenda-Setting. Sage; 1996.

8. McCombs M, Reynolds A. How the news shapes our civic agenda. In: Bryant J, Oliver MB, eds. Media Effects: Advances in Theory and Research. Taylor & Francis; 2009:1-17.

9. Scheufele D, Tewksbury D. Framing, agenda setting, and priming: The evolution of three media effects models. J Commun. 2007;57(1):9-20.

10. Entman RM. Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm. J Commun. 1993;43(4):51-58. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

11. Iyengar S. Is Anyone Responsible?: How Television Frames Political Issues. University of Chicago Press; 1994.

12. Altheide DL. Reflections: Ethnographic content analysis. Qual Sociol. 1987;10(1):65-77. doi:10.1007/bf00988269

13. Green SJ. Seattle police: Maintenance worker at a Belltown apartment building was fatally stabbed by evicted tenant. The Seattle Times. Published September 24, 2020. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/law-justice/seattle-police-maintenance-worker-at-a-belltown-apartment-building-was-fatally-stabbed-by-evicted-tenant/

14. Schaff K, Dorfman L. Local Health Departments Addressing the Social Determinants of Health: A National Survey on the Foreclosure Crisis. Health Equity. 2019;3(1). doi:10.1089/heq.2018.0066

15. Nixon L, Schaff K, Mejia P, Marvel D, Dorfman L. Equity and Health in Housing Coverage: A Preliminary News Analysis from Northern California. Berkeley Media Studies Group; 2019. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.bmsg.org/resources/publications/equity-and-health-in-housing-coverage-a-preliminary-news-analysis-from-northern-california/

16. Krippendorff K. The Content Analysis Reader. SAGE Publications, Inc; 2009.

17. No reason to go back; Following a court order, Phila. may have just revolutionized evictions. The Philadelphia Inquirer. Published April 6, 2021. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.inquirer.com/opinion/editorials/eviction-moratorium-philadelphia-diversion-renters-rights-20210604.html

18. Williams J. HANO wins $5.7 million grants to offer more vouchers, hire more staff. The Times-Picayune/The New Orleans Advocate Online. Published May 24, 2021. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.nola.com/news/article_22b9df7a-bca7-11eb-8f37-53834a1abeee.html

19. Grigsby S. West Oak Cliff divided over plan to protect it. The Dallas Morning News. Published May 23, 2021. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.dallasnews.com/news/commentary/2021/05/21/fear-mistrust-and-an-election-hangover-threaten-west-oak-cliff-master-plan-can-it-survive/

20. DuBose B. HACA sounds the alarms over eviction risk More than 40% of residents face threat in 2021. The Baltimore Sun. December 13, 2020:1.

21. Fitzgerald T, Whelan A. Closing Kensington shelter of last resort; Many see El station’s closure as a link in the city’s long chain of failures in a neighborhood overwhelmed by heroin and homelessness. The Philadelphia Inquirer. Published March 28, 2021. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.inquirer.com/transportation/el-train-somerset-stop-septa-kensington-heroin-20210328.html

22. Rosen E, McCabe B. D.C. makes eviction filings too easy. The Washington Post. Published November 6, 2020. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/local-opinions/dc-makes-eviction-filings-too-easy/2020/11/05/ec441a88-1304-11eb-ad6f-36c93e6e94fb_story.html

23. Freedman J. Letters to the Editor: The problem with building “affordable” housing in affluent neighborhoods. Los Angeles Times. Published March 2, 2021. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://sports.yahoo.com/letters-editor-problem-building-affordable-110044982.html

24. Lazarus J. Virginia Supreme Court halts most evictions through Sept. 7. Richmond Free Press. Published August 13, 2020. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://richmondfreepress.com/news/2020/aug/13/virginia-supreme-court-halts-most-evictions-throug/

25. Collins J. Indicators & Insights; Eviction clouds gather. Orange County Register. October 25, 2020:1.

26. Kudisch B. Mercer County renters struggling to make payments amid coronavirus pandemic. NJ.com. Published August 29, 2020. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.nj.com/mercer/2020/08/mercer-county-renters-struggling-to-make-payments-amid-coronavirus-pandemic.html

27. Chen D, Chen S. What Will New York Real Estate Look Like Next Year? The New York Times. Published October 23, 2020. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/23/realestate/nyc-housing-future.html

28. Richardson R. Planning a more equitable SoCal. Press-Telegram. Published July 6, 2020. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.presstelegram.com/2020/07/06/planning-a-more-equitable-socal-rex-richardson/

29. Bond M. 70% of most polluted plots are within a mile of low-income communities of color, new report says. The Philadelphia Inquirer. Published July 15, 2020. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.inquirer.com/news/environmental-justice-superfund-nj-shriver-center-20200714.html

30. Rahman N. Lack of Black neighbors in Detroit’s Islandview rentals leads to Fair Housing Act lawsuit. Detroit Free Press. Published February 11, 2021. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.freep.com/story/news/local/michigan/detroit/2021/02/11/fair-housing-act-lawsuit-lack-of-black-neighbors/4259105001/

31. Gergen Barnett K, Sandel M. For good health outcomes, we need good housing incomes. The Boston Globe. Published January 23, 2021. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.bostonglobe.com/2021/01/23/opinion/good-health-outcomes-we-need-good-housing-incomes/

32. Holston G, Collier R. Rent protections key to equality in Philadelphia. The Philadelphia Inquirer. Published June 4, 2020. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.inquirer.com/opinion/commentary/philadelphia-housing-rental-protection-helen-gym-jamie-gauthier-kendra-brooks-20200603.html

33. Lopez S. Column: He went from Yale to Wall Street to homelessness. Now he’s rising back up. Los Angeles Times. Published April 17, 2021. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2021-04-17/column-from-high-school-brain-to-yale-to-wall-street-to-homelessness-and-now-rising-back-up

34. Logan T. New efforts to block evictions; Bills in progress on state, national level. The Boston Globe. June 30, 2020:1.

35. Tobias M. “Through the Cracks”: California’s landmark rent relief program may leave scores of tenants, landlords behind. North Coast Journal. Published May 16, 2021. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.northcoastjournal.com/humboldt/through-the-cracks/Content?oid=20344615

36. Chesto J. Boston gets flexibility on affordable housing link. The Boston Globe. January 14, 2021:1.

37. Oreskes B. Biden’s plans may offer hope to L.A.’s homeless population — if Congress goes along. Los Angeles Times. Published January 22, 2021. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.latimes.com/homeless-housing/story/2021-01-22/bidens-plans-may-offer-hope-to-l-a-s-homeless-if-congress-goes-along

38. Dorfman L, Wallack L, Woodruff K. More than a message: Framing public health advocacy to change corporate practices. Health Educ Behav. 2005;32(4):320-336.

39. McGreevy P. No deal yet in Sacramento to help struggling California renters. Los Angeles Times. Published August 20, 2020. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2020-08-20/no-deal-yet-on-help-california-renters-evictions-housing

40. Reagor C. Rising prices, shortage of affordable homes deepen housing squeeze; Demand in the Phoenix area has stayed strong despite the pandemic. The Arizona Republic. Published April 4, 2021. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.azcentral.com/story/money/real-estate/catherine-reagor/2021/04/04/phoenix-housing-market-record-home-prices/4827175001/

41. Larson S. READERS WRITE Protect and serve whom? Star Tribune. June 24, 2020:8.

42. Khouri A. Eviction bans put landlords in a bind; Small owners are draining savings, delaying repairs as pandemic rules shield nonpaying tenants. KTLA75. Published April 5, 2021. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://ktla.com/news/local-news/landlords-say-rules-letting-pandemic-affected-tenants-keep-housing-if-they-dont-pay-rent-are-heaping-an-increasingly-unfair-burden-on-them/

43. Capelouto J. Eviction hearings quietly resuming across metro Atlanta. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Published August 6, 2020. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.ajc.com/news/atlanta-news/eviction-hearings-quietly-resuming-across-metro-atlanta/MXKISPC4FRDYRNTBHCXRUGTZYM/

44. McGreevy P. Lawmakers nearing vote on evictions; Compromise between landlord and renter demands faces a high hurdle in Legislature. Los Angeles Times. August 29, 2020:B.

45. Cooper A, Shenker-Osorio A. Messaging for More: The False Story of Scarcity. Lightbox Collaborative. Accessed April 19, 2022. https://www.lightboxcollaborative.com/2017/07/28/messaging-more-false-story-scarcity/

46. Brownstone S. Washington may soon be first state to guarantee lawyers for low-income tenants facing eviction. The Seattle Times. Published April 10, 2021. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/homeless/washington-could-become-first-state-to-guarantee-lawyers-for-low-income-tenants-facing-eviction/

47. Reyes E. Proposed L.A. law banning landlords from harassing renters clears a key hurdle. Los Angeles Times. Published April 14, 2021. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2021-04-14/la-tenant-harassment-ordinance-city-council

48. Barney C. Share the Spirit: Rainbow Center works to support LGBTQI+ community. The Mercury News. Published December 29, 2020. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.mercurynews.com/2020/12/29/share-the-spirit-rainbow-center-works-to-support-lgbtqi-youth/

49. Oreskes B. Garcetti’s signature homeless program shelters thousands, but most return to the streets. Los Angeles Times. Published November 20, 2020. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.latimes.com/homeless-housing/story/2020-11-20/garcetti-a-bridge-home-homeless-program-offers-mixed-results

50. Lopez S. Column: She is naked, sick, dirty, crawling across Sunset Boulevard — how can this happen in L.A.? Los Angeles Times. Published October 10, 2020. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2020-10-10/homeless-woman-silver-lake-mental-illness

51. Gordon M, Noonan K. Housing helped many homeless people survive coronavirus. Now what? The Philadelphia Inquirer. Published June 11, 2020. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.inquirer.com/opinion/commentary/coronavirus-covid-homeless-housing-first-20200610.html

52. Greenstone S. At Denny Park, Seattle quietly tries to remove homeless encampment. The Seattle Times. Published March 3, 2021. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/homeless/at-denny-park-city-is-quietly-trying-to-sweep-homeless-campers-without-police/

53. Buchta J. In effort to preserve affordable houses, Edina program takes aim at teardowns. Star Tribune. Published April 17, 2021. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.startribune.com/in-effort-to-preserve-affordable-houses-edina-program-takes-aim-at-teardowns/600047273/

54. Smith D, Oreskes B, Holland G. L.A. falls far short of COVID-19 promise to house 15,000 homeless people in hotels. Los Angeles Times. Published June 22, 2020. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.latimes.com/homeless-housing/story/2020-06-22/homeless-people-motels-hotels-los-angeles-county

55. Hanks D. In a day, more than 35,000 people sign up for Miami-Dade’s new Section 8 waiting list. The Miami Herald. Published May 13, 2021. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://account.miamiherald.com/paywall/subscriber-only?resume=251391883&intcid=ab_archive

56. Nixon L, Mejia P, Cheyne A, Wilking C, Dorfman L, Daynard R. “We’re Part of the Solution”: Evolution of the Food and Beverage Industry’s Framing of Obesity Concerns Between 2000 and 2012. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(11):2228-2236.

57. Tippett K. Trabian Shorters: A Cognitive Skill to Magnify Humanity. Accessed April 19, 2022. https://onbeing.org/programs/trabian-shorters-a-cognitive-skill-to-magnify-humanity/

58. Community Change, PolicyLink, Race Forward. Housing Justice Narrative. Published 2022. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://housingnarrative.org/

59. Gehlert H. Alameda County Department of Public Health GRAND PRIZE WINNER Arnold X. Perkins Award For Outstanding Health Equity Practice. Berkeley Media Studies Group; 2015. Accessed June 13, 2022. https://www.bmsg.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/bmsg_tce_alameda_health_equity_case_study.pdf

60. Gehlert H, Schaff K. Six media advocacy lessons from a campaign for housing justice and health equity. Berkeley Media Studies Group. Published December 8, 2021. Accessed April 19, 2022. https://www.bmsg.org/blog/six-media-advocacy-lessons-from-a-campaign-for-housing-justice-and-health-equity/

61. The Praxis Project. Fair Game: A Strategy Guide for Racial Justice Communication in the Obama Era. The Praxis Project; 2011.

62. Axel-Lute M. How Do We Change the Narrative Around Housing? Shelterforce. Published July 27, 2020. Accessed June 13, 2022. https://shelterforce.org/2020/07/27/how-do-we-change-the-narrative-around-housing/

63. Race-Class: Our Progressive Narrative. Demos; 2018. Accessed September 10, 2021. https://www.demos.org/sites/default/files/publications/Race_Class_Narrative_Handout_C3_June%206.pdf

64. We Make the Future Action. Published 2022. Accessed June 13, 2022. https://www.wemakethefutureaction.us/.