Elevating Latino experiences and voices in news about racial equity: Findings and recommendations for more complete coverage

Wednesday, March 15, 2023Introduction

Every day, Latinos in the United States encounter — and work to dismantle — many forms of inequality. Latinos are disproportionately killed by police,1 face unaffordable rent and high risks of homelessness,2 and are more likely than non-Latino groups to experience hunger and material hardship,3 like difficulty paying bills. These are all racial injustices, rooted in fundamentally unequal systems and structures, but do we recognize them as such? And are connections between racial injustices and Latinos, the country’s largest ethnic minority, clear?

Studying whether — and how — these issues appear in the news can give us answers. That’s because news institutions play a powerful role in shaping public conversations. Journalists provide both policymakers and the public with information on events, trends, social injustices, and other developments in our communities, the nation, and beyond. Knowing how issues are discussed in the media, then, gives us a baseline for understanding how people are — or aren’t — thinking about our world’s challenges, who is affected by them, and what solutions seem possible.4, 5, 6

Beyond telling stories, the news can be a powerful vehicle for positive social change. Carefully crafted news can uplift dignified and humanizing stories that reflect the power of communities whose perspectives have been excluded from history books. Too often, however, news coverage preserves, upholds, and weaponizes harmful, discriminatory, and racist narratives about people of color and marginalized communities.7

Without visibility, even the basic facts about how a societal issue affects Latinos may be lost. Furthermore, in the absence of inclusive news coverage, the contributions, challenges, and needs of Latino communities may be overlooked, or poorly understood, by policymakers, their allies in the fight for racial equity, and the public in general.

For journalists to avoid causing — and compounding — harm, they must tell fair, accurate, and complete stories that feature a range of perspectives, including those of Latinos, across all reporting beats. Doing so is a critical step toward building and maintaining an inclusive, just, and transformative narrative about racial equity in the U.S.

Fortunately, in recent years we’ve seen more awareness of and discussion about whether the people who tell our stories and catalog our history reflect the communities they represent. Yet, a large gap between discussion and positive action remains. Surveys from Pew Research Center have found that journalists rate the news industry poorly when it comes to diversity, especially for racial and ethnic groups.8 Indeed, according to a study by the U.S. Government Accountability Office, only 11% of news analysts, reporters, and journalists are Latino.9 This lack of newsroom diversity harms news quality and employee morale, and research has shown that diverse newsrooms are more profitable10 — an important consideration amid continued budget cuts and industry layoffs.

Journalists and reporters of color have long protested11 against the predominantly white and male lens of news coverage, and the culture of newsrooms themselves,12 by establishing advocacy groups, including the National Association of Hispanic Journalists. Similarly, Latino+ communities and leaders have been at the forefront of organizing around racial equity for decades, but there is concern that their perspectives and voices are underrepresented in the surging public discourse around racial equity and systemic racism.13

To gain a window into the current state of public discourse surrounding racial equity and to identify opportunities for improvement, BMSG researchers, in consultation with UnidosUS, explored how Latino communities have been represented in national news about both racism and racial equity (including news about issues like inequities in wealth, housing, and health). We reviewed news published in both print and online national outlets. We studied the content, tone, and perspectives included in or excluded from news coverage and used our findings to make recommendations for journalists, advocates, and philanthropists to expand and deepen their understanding of racial equity and to improve news coverage of Latinos.

Who we are

Berkeley Media Studies Group (BMSG), a program of the Public Health Institute, was founded in 1993 and is dedicated to expanding the ability of public health professionals, journalists, and community groups to improve the systems and structures that determine health and safety. . We do this by helping people use the power of the media to make their voices heard and increase their participation in the democratic process. Our approach is grounded in three decades of examining — and working to shift — narratives around public health and social justice issues to achieve racial and health equity.

UnidosUS is a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization that serves as the nation’s largest Hispanic civil rights and advocacy organization. Since 1968, we have challenged the social, economic, and political barriers that affect Latinos through our unique combination of expert research, advocacy, programs, and an Affiliate Network of nearly 300 community-based organizations across the United States and Puerto Rico. We believe in an America where economic, political, and social progress is a reality for all Latinos, and we collaborate across communities to achieve it. For more information on UnidosUS, visit unidosus.org or follow us on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.

What we did

BMSG used LexisNexis and ProQuest, databases of print and online news publications, to search for articles about racism and racial equity from around the United States published between May 1 and September 30 in 2020, 2021, and 2022; we selected these time periods because they coincided with the height of news about racism and racial equity, with the onset of protests in response to racist killings by police in the U.S. in 2020, as well as the anniversaries of those protests.

We collected the metadata of articles to compare two sets of stories:

- News about racial equity: We identified news about racism and racial equity issues by searching for articles that used terms like “inequity,” “police violence,” “wealth gap,” and “housing gap.”

- News about racial equity and Latinos: We identified news about racism and racial equity that also included at least one variation of a term like “Hispanic,” “Latino/a/x/e,” or country-specific terms accounting for all Latin-American countries (such as “Mexican” or “Brazilian”).

To learn more about who was quoted in the second set of articles, and what they said, we then conducted an ethnographic content analysis using a sample of articles published during the 2022 sample period. We used qualitative analysis software to code and analyze our final sample of 62 relevant articles (scientifically selected to ensure the results are generalizable).

For a complete overview of our methods, please see Appendix A.

Why it matters

This study is unique in that we explored news coverage of the various ways systemic racism shapes the social conditions of Latino communities — in terms of, for example, inequities in health care, wealth, and education. Previous research on the representation of Latino communities in the media has examined specific issues and narratives, with many studies focused on the portrayal of immigrants.14, 15, 16 This study also breaks new ground in that we assess, to the best of our ability (see Appendix A), the visibility of Latinos as sources in stories and as news creators.

Although we focus this study on the presence and absence of Latinos in news coverage, the findings offer a window into a broader conversation about the need for newsrooms staffed by reporters and editors who represent every community. More diverse newsrooms, in turn, can help tell a more transformative and inclusive narrative about our country and the challenges — and opportunities — we face.

What we found: What the numbers tell us

Finding: Racism and racial equity were major news topics in 2020, though coverage fell dramatically in 2021 and 2022. Across years, only 5.6% of articles referenced Latinos.

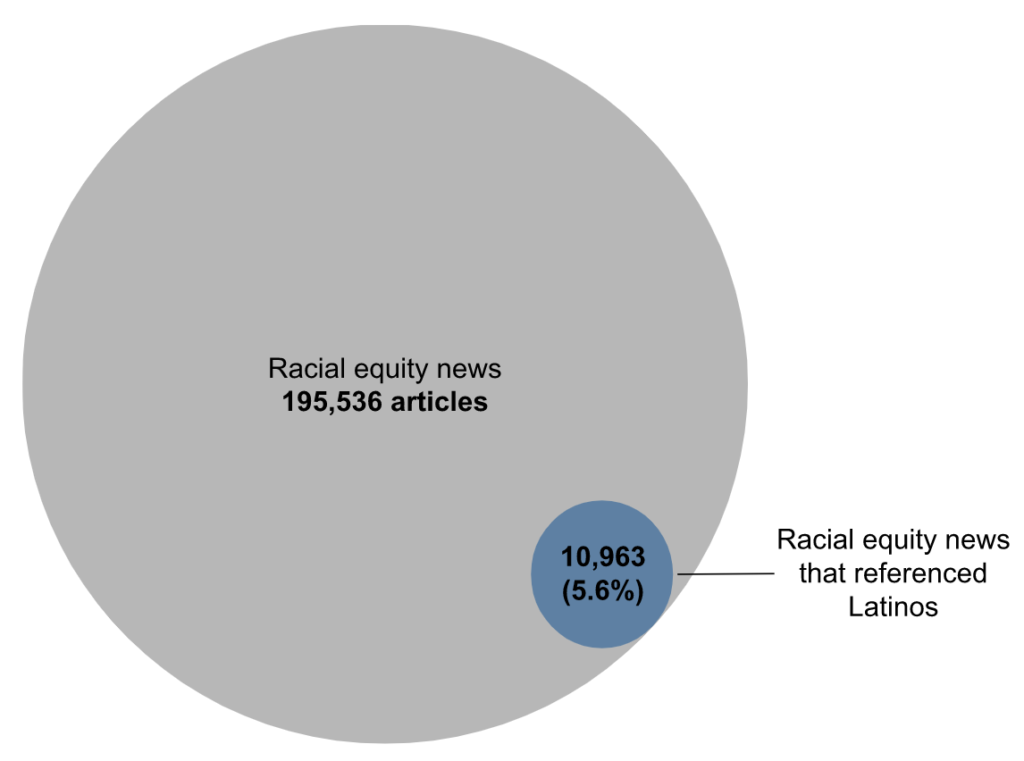

We found a total of 195,536 articles that covered racial equity and related issues published between May 1 and September 30 in 2020, 2021, and 2022 (see Appendix A for methods). Of those, 10,963 articles referenced Latinos — only 5.6% of all racial equity news (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Total volume of news about racial equity and of news about racial equity and Latinos, published in U.S. news outlets (May 1st – September 30, in 2020, 2021, and 2022).

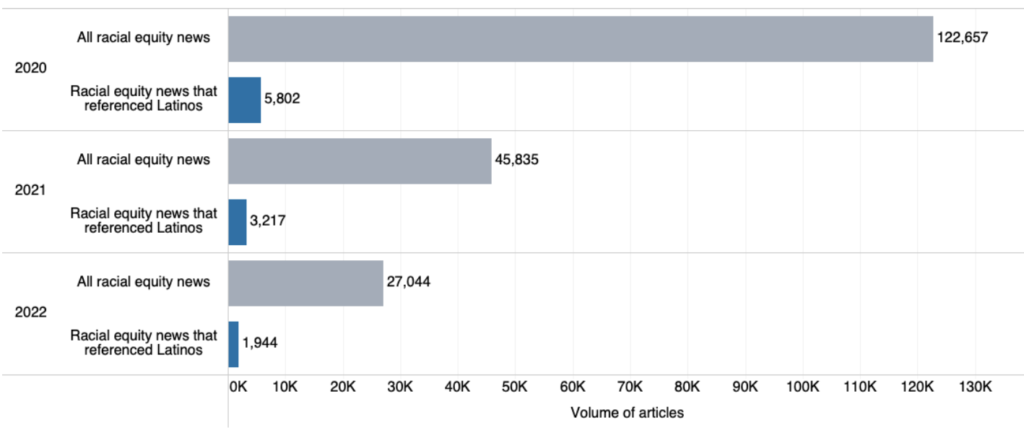

Overall, the volume of coverage in 2020 was three to four times higher than in 2021 and 2022 (see Figure 2). Latinos were referenced in 5% of news coverage in 2020, compared to 7% of coverage in 2021 and 2022.

Figure 2. Volume of all news about racial equity and of news about racial equity and Latinos, published in U.S. news outlets (May 1 – September 30, in 2020, 2021, and 2022).

Finding: California newspapers published the most news about racial equity and Latinos, but Latinos were still underrepresented, given the state’s high Latino population.

Several high-circulation national outlets such as The New York Times and USA TODAY published large volumes of news about racism and racial equity (see Figure 3). However, less than 10% of the news about racial equity published in each of these outlets referenced Latinos. By contrast, The Washington Post was the outlet that published the highest proportion of racial equity news that referenced Latinos (17.8% of their coverage); however, this difference may be in part attributable to the different methodology used to retrieve stories from this outlet (see Appendix A for more information).

Figure 3. Outlets that published the highest proportion of news about racial equity and Latinos (May 1 – September 30, in 2020, 2021, and 2022).

| Publication | Racial equity news | Racial equity news that referenced Latinos | Proportion of racial equity news that referenced Latinos |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Washington Post* | 3,048 | 542 | 17.8% |

| Los Angeles Times | 1,714 | 172 | 10.0% |

| The Philadelphia Tribune | 2,314 | 225 | 9.7% |

| USA TODAY | 1,896 | 173 | 9.1% |

| San Francisco Chronicle | 2,870 | 243 | 8.5% |

| The New York Times | 7,124 | 508 | 7.1% |

| The Mercury News | 1,598 | 94 | 5.9% |

| The East Bay Times | 1,604 | 87 | 5.4% |

| The Examiner (Washington, D.C.) | 2,069 | 68 | 3.3% |

| The Seattle Times | 1,580 | 51 | 3.2% |

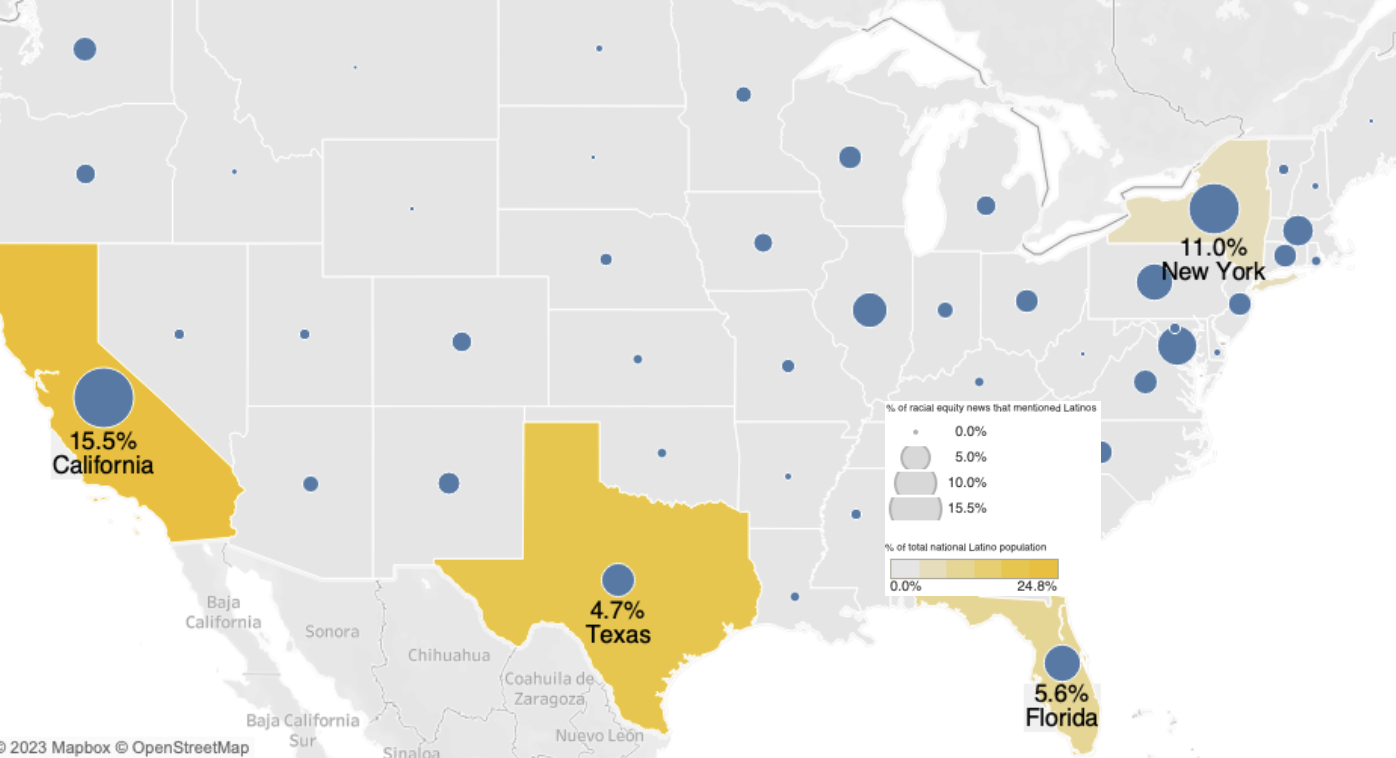

Of all news articles about racial equity published in the U.S., California newspapers published the most coverage that referenced Latinos (15.5% of all articles about racial equity and Latinos in the U.S., see Figure 4). However, that coverage still fell far short of representing the state’s demographics: According to the American Community Survey 2021, a quarter of all Latinos in the U.S. live in California.17 We found an even steeper disparity in news out of Texas: Just 4.7% of all racial equity news that referenced Latinos was published in Texas, where about 19% of the nation’s Latinos live.17 Additionally, a small number of journalists wrote the bulk of the articles that referenced Latinos, giving audiences an even more limited perspective on issues facing the country’s largest ethnic minority.

Figure 4. Geographic distribution of racial equity news that referenced Latinos published in U.S. outlets, compared to proportion of national Latino population by state (May 1 – September 30, in 2020, 2021, and 2022).

What we found: What stories about racial equity and Latinos tell us

Finding: News articles most often used terms like Hispanic, Latino, or Latina.

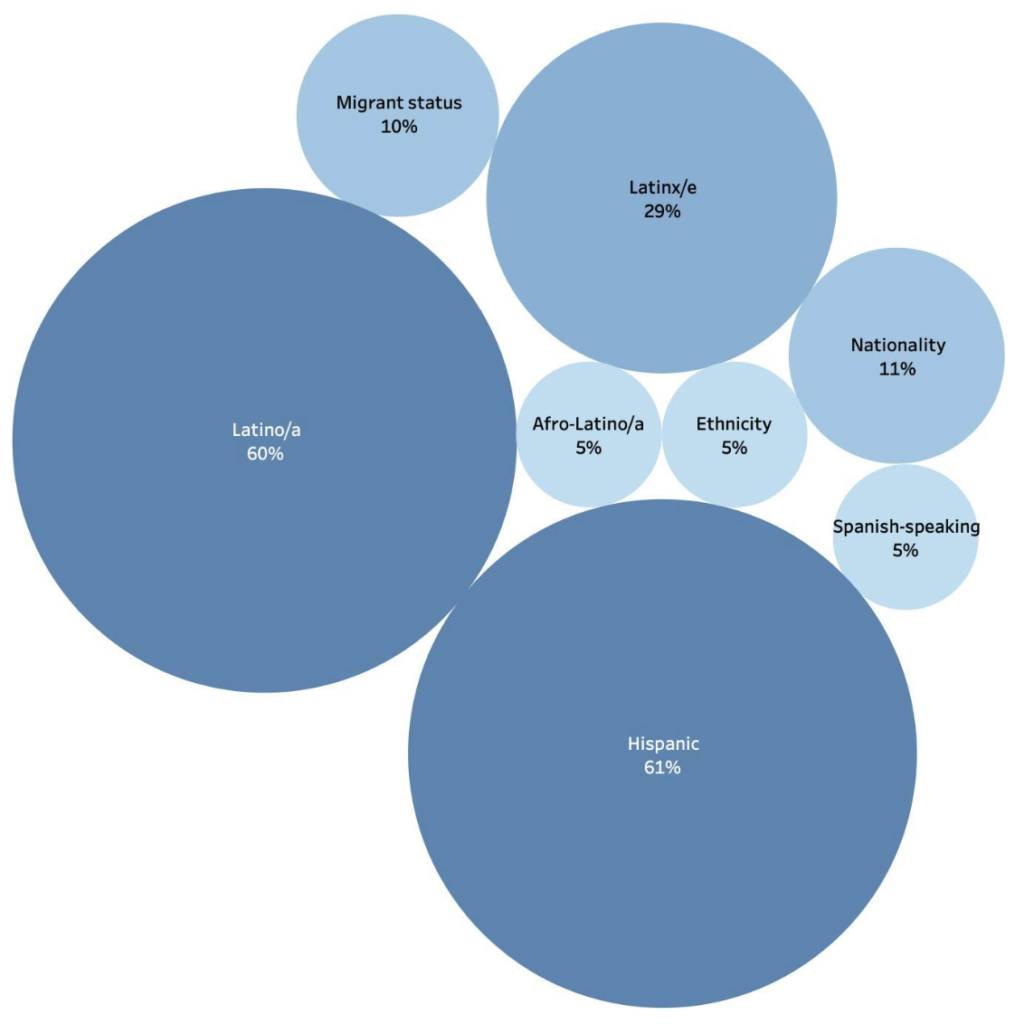

Latino communities were described in multiple ways in news articles, and some articles used more than one descriptor (see Figure 5). The most frequently used terms were Hispanic and Latino or Latina, which appeared in 61% and 60% of articles, respectively. Latinx or Latine appeared in 29% of articles. Descriptions based on nationality (i.e., birthplace) were used in 11% of articles, and a few articles described Latino communities as Spanish-speaking or Afro-Latino/a.

Figure 5. Demographic descriptions in news about racial equity and Latinos, published in U.S. news outlets (May 1 – September 30, in 2020, 2021, and 2022). (n = 62 relevant articles)

Finding: Few authors could be identified as Latino.

In our qualitative analysis, we found no authors of news articles who could be explicitly identified as Latino (see Appendix A). Using contextual clues like names, we were able to identify just 15% of authors as Latino (see Appendix B). For more information about journalists who frequently wrote about Latinos, see Appendix C.

Defining Latino identity is complex and depends on a range of factors — only some of which may be apparent in print news coverage. To accommodate that complexity to the best of our ability, we differentiated between identifications of Latinos: explicit identification based on descriptions in the article or self-identification by speakers themselves, and implicit identification using contextual clues like surnames. We erred on the side of conservative coding; however, we recognize that our findings may underreport the prevalence of Latino speakers and authors. To learn more about how we identified authors and speakers as Latino, please see Appendix A.

Finding: News coverage described problems facing Latinos, but named solutions less often.

A typical question we ask when we analyze news about any subject is: How are problems and solutions characterized? From decades of research, we know that media narratives tend to focus on problems, rather than solutions.18 When the news fails to illustrate a way forward, it can be difficult for readers to see the possibility and promise of solutions, making the problems seem all the more intractable.

Since we evaluated stories about Latinos and racial equity issues like wealth and housing gaps, it is perhaps unsurprising that 81% of articles described at least one problem affecting Latinos. The problems that journalists identified as affecting Latinos spanned a wide range of issues: Among the most commonly named were racism, as well as problems rooted in racial inequity, such as a widening wealth gap, health disparities, and inadequate health insurance coverage.

By contrast, solutions to address problems affecting Latinos were named in fewer than 40% of articles. Most of the solutions named related to closing the wealth gap,19 improving housing and homeownership rates,20 and advancing educational attainment.21

Finding: Authentic voices appeared in only one-third of articles about racial equity and Latinos.

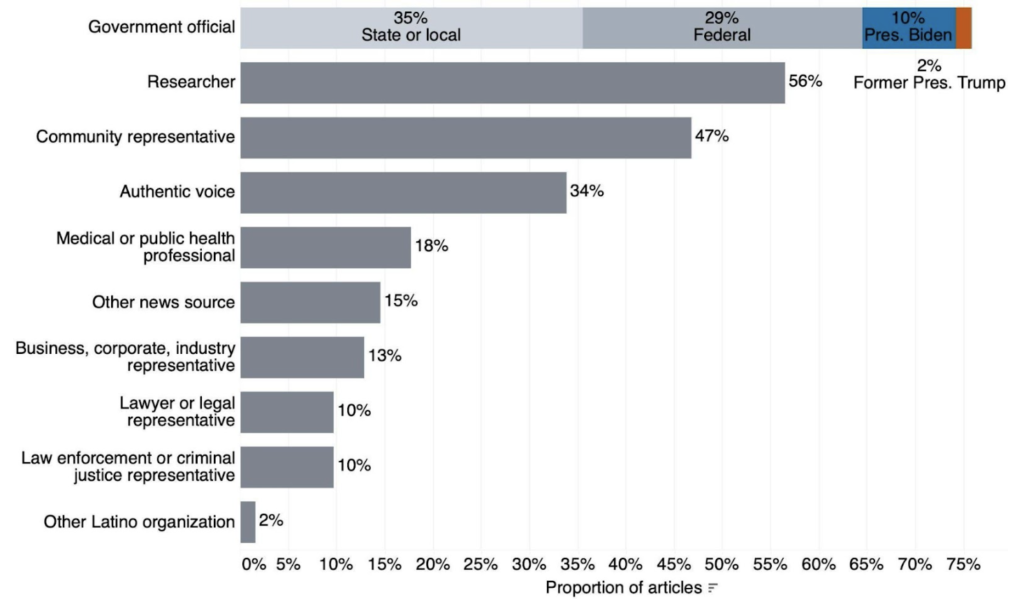

It’s important to understand who speaks in the news because the messenger is just as important as the message: Sources quoted in news articles can provide credibility and unique perspectives on problems and solutions.22 Given the diversity of issues in our sample, we documented a broad range of speakers in the news, regardless of whether they were quoted talking about Latinos (see Figure 6).

Authentic voices — that is, people speaking from lived experience of an issue who were not otherwise affiliated with an organization or profession — were quoted in 34% of articles. Examples included a Salvadoran mom struggling to find formula for her baby23 and a congregant from a majority-Latino immigrant church embroiled in scandal.24

Overall, the most frequently quoted speakers were government officials or government agency representatives (76% of articles); researchers from academia, think tanks, or public oversight groups (56%); and community representatives affiliated with social justice organizations, schools, and religious institutions (47%).

Figure 6. Speakers in news about racial equity and Latinos, published in U.S. news outlets (May 1 – September 30, in 2020, 2021, and 2022). (n = 62 relevant articles)

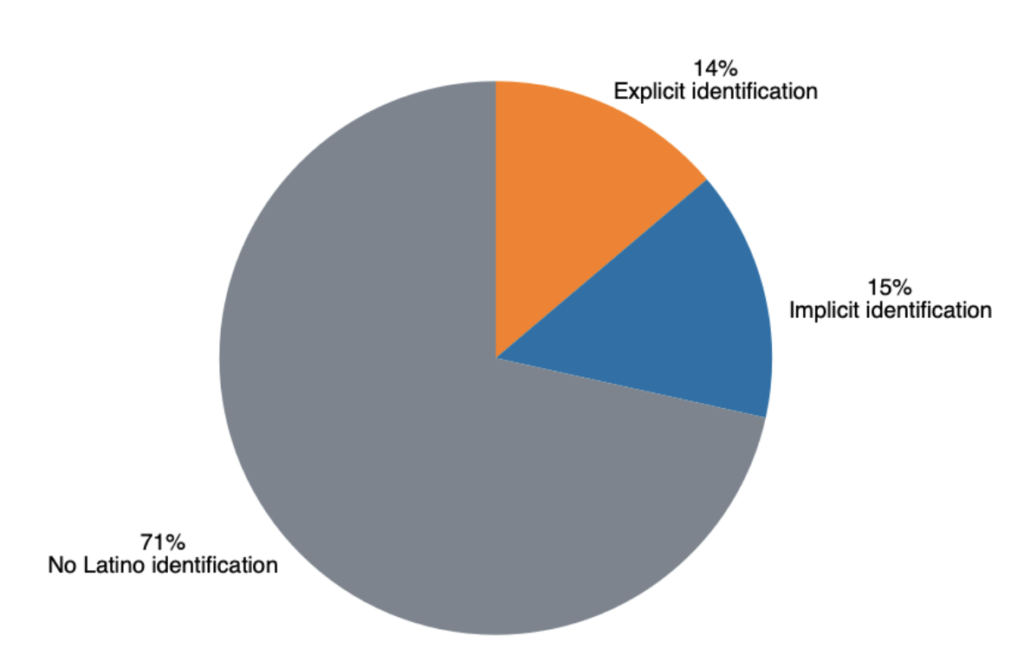

Finding: Few speakers/sources could be identified as Latino.

Based on our criteria (see Appendix A), only 14% of articles explicitly identified speakers as Latino (see Figure 7). Some articles provided descriptive details about the speaker’s ethnicity, as when a journalist described a college student as Mexican American.25 Occasionally, speakers describing their lived experiences (as parents, congregants, writers, or representatives of community organizations) self-identified as Latino, as when a representative from a women’s advocacy organization described herself as “a Latina and a mother.”26

We were also interested in understanding how, if at all, Latino speakers were depicted as agents of or advocates for change. Often, speakers quoted in news stories are called upon to provide personal details about their experiences but not to connect these details to calls for solutions. Latinos were rarely characterized as agents of change at the helm of solutions. A rare example focused on a local health department’s efforts to involve Latino communities in planning, with a coordinator noting, “the Latinx community needed to be heard … [so] the Department of Health and Human Services can create changes in policies, initiatives, programs and events that would benefit the Latinx community.”27 Only two articles included a call to action with solutions supporting Latino communities. However, these calls to action were not voiced by speakers who were readily identifiable as Latinos.

Figure 7. Articles with Latino-identified speakers in news about racial equity and Latinos, published in U.S. news outlets (May 1 – September 30, in 2020, 2021, and 2022). (n = 62 relevant articles)

Finding: Latino organizations rarely appeared in the news.

Only one representative from a Latino advocacy organization, Chicanos por la Causa, an UnidosUS affiliate, was quoted in our sample. Overall, we found that Latino organizations rarely appeared in racial equity news. Since Latino advocacy organizations might be expected to have informed perspectives on the scope of certain problems and/or solutions, the scarcity of their appearances in the news could deny readers access to important information.

Summary

Our analysis of national news from three time periods suggests that:

- Racism and racial equity were major news topics in 2020 (though coverage fell dramatically in 2021 and 2022), and across the board, news rarely referenced Latinos.

- California newspapers published the most stories about racial equity that also mentioned Latinos; however, Latinos were still underrepresented in news coverage in that state.

- News coverage tended to focus on problems facing Latino communities, with only 40% of articles mentioning solutions. When solutions did appear, they were related to closing the wealth gap, improving housing and homeownership, and advancing educational attainment.

- Few authors or speakers could be identified as Latino, and organizations representing Latinos rarely appeared in the news.

Recommendations

In 2019, the documentary “This Changes Everything” revealed a stunning lack of gender parity at every level in Hollywood. Produced by Geena Davis, who founded her own media institute in 2004 to fill a critical gap in research, the film exposed discrimination across all categories and ratings of movies and television and found that the ratio of male to female characters was the worst in kids’ programming.28 Thanks in large part to the institute’s research and efforts to improve gender parity, children’s television shows are now far more inclusive,29 with nearly equal representation of prominent male and female characters; however, gender diversity in kid-focused films still lags,30 with male leads remaining twice as common as female leads.

Such challenges are not unique to gender — or to Hollywood — and the research shared in the film expanded the opening that advocates and media professionals have for discussing diversity in all its forms. Our researchers took many of the same questions Davis asked about gender in movies — Who is or isn’t being represented? What are the implications for viewers? How can we address this bias? — and applied them to racial equity in the news. While our findings about Latino underrepresentation in news about racial equity may seem discouraging, like Davis, we know that the only way we can solve problems is to first identify them, name them, and make others aware that they exist.

Change is happening as newsrooms become more diverse and put their own coverage under the microscope, but progress is slow31 and little attention has been given specifically to Latino representation. Our findings create an opportunity for journalists and publishers to expand and deepen their understanding of racial equity and how Latinos are affected. Philanthropists and advocates can be partners, helping to ensure that journalists always have access to diverse sources and perspectives at the ready. Here are a few suggestions to help elevate Latinos within news about racial inequities, starting with considerations for how to frame this topic.

Create messages that explicitly frame inequities facing Latinos as racial equity issues.

This is something that everyone can do, whether they are approaching the issue as a journalist, philanthropist, organizer, or simply as a concerned resident. A common question we get at BMSG when our research exposes an omission in the news is: How can we increase coverage of one important issue or group without decreasing it of another?

We believe it is possible to elevate underrepresented voices without pitting one community against another, which risks race becoming a wedge that stokes further division.32 To avoid this trap, think of equity not as a pie to be “portioned out,” but as a tide that lifts all boats. Inclusive coverage does not necessarily mean that the overall volume of coverage must change. Rather, its framing does. You can start by brainstorming the following:

- Whenever there is a story about [fill in the blank] aspect of racial equity, it must include Latinos.

- Whenever there is a story about Latinos, it must include [fill in the blank] aspect of racial equity.

Doing so can help demonstrate how policies affect Latinos across all issues. A racial equity angle can be applied to health, housing, education, and more. For example, Latinos may be represented in policy decisions, but the public may not know it. Make those kinds of links explicit, and connect dots for the reader in your messages, stories, and other public-facing materials.

Recommendations for reporters

Broaden your sources.

One of the fastest ways to ensure more representative coverage is to ensure that your sources come from diverse backgrounds and include Latinos. But the effort doesn’t stop there. It’s common for reporters to reach out to individual residents to put a human face to a common struggle in an effort to help readers better empathize. Try extending that same thinking to reporting on data and solutions. Who do you consider an “expert” source? Is it someone with a professional affiliation? A particular degree? If so, it may be helpful to rethink what constitutes expertise and how lived experience is a form of expertise: A lay person may still have a deep well of knowledge and understanding to draw from. Similarly, researchers and other more traditionally recognized experts may have personal backgrounds that have shaped their approach to interpreting data. For additional guidance on incorporating the experiences of marginalized communities, see the Solidarity Journalism Initiative from the Center for Media Engagement at the University of Texas at Austin.

Ask more — and more nuanced — questions.

Time is a luxury that journalists rarely have. Rather than trying to take on extra stories amid an already demanding schedule, some shifts to how you approach storytelling can help make your stories more thorough and inclusive. This involves looking at old questions in new ways and using an equity mindset to inform the questions you ask. In practice, that might look like this:

| In addition to: | Ask: |

|---|---|

| What is the problem? | What can we do about it? What’s already being done? Who is having success? |

| How are communities of color affected? | How is this issue experienced differently across various communities? Where are the commonalities? |

| Who has conducted research on this? | Has a person or group from the affected community conducted research on this? |

What is the solution? | How have communities been involved in developing solutions? Who benefits from the solution? |

Rethink common language choices.

Language matters, and journalists often update industry guidance on what words and phrases to use or avoid. But nuance matters, too. Although Latinos often share a common heritage and many agree on major policy positions,33 they are not a monolith: Latinos comprise many different cultures and nationalities. When interviewing sources, take those caveats into account. In addition to considering broader cultural and policy contexts, ask your sources how they want to be identified, e.g., Latino/a? Latinx? Latine? Hispanic? Those conversations can inform not only your own articles but also your newsroom’s editorial guidelines.

Recommendations for publishers & newsroom leaders

The above recommendations for journalists are necessary but not enough on their own to create more equitable, inclusive coverage. It is critical for industry leaders to continue assessing and refining newsroom hiring and recruiting practices to help close the byline gap and create diverse teams that reflect the communities they cover. This requires looking not only at overall numbers within your masthead but at diversity within leadership positions. Who is reporting the stories? Editing them? Planning the editorial calendar? Making decisions when there are disagreements?

One strategy to consider is collaborating with other newsrooms. Many outlets are already doing this with topic-specific coverage like climate change (see the Local Media Association’s Covering Climate Collaborative) and helping to amplify the work of smaller outlets; a similar approach could be applied to reporting on racial equity. Cross collaboration would ensure that a wider range of perspectives make it into your coverage and onto the screens of your readers and viewers.

Recommendations for philanthropists

Invest in providing media relations and strategic communication training for Latino researchers and community groups.

Providing opportunities for grantees to receive media training can yield big dividends. Researchers can learn how to better translate findings into lay terms that appeal to broader audiences outside of medical journals; community groups can put strategic communication skills to use in writing opinion pieces and letters to the editor and/or serving as interview sources for reporters. Participants can walk away from trainings with new story ideas, talking points, contacts, and more. Many of the same skills used for traditional press outreach can also be used for “owned media” like podcasts and self-published blogs.

Create and share press lists with grantees.

When advocates are busy, it’s not uncommon for basic logistical tasks to get relegated to the back burner of their always-maxed-out stovetop. Compiling media outreach lists can help jumpstart their efforts to build relationships with journalists. If you are able to, make connections by doing email introductions. Networking takes time, and although sharing contacts is not a substitute for one-on-one conversations between journalists and potential sources, it can speed up the process of building rapport.

Recommendations for advocates

Build relationships with the media, especially regional and smaller outlets with high populations of Latinos.

Latinos were underrepresented in news coverage of racial equity across all locations. To correct this imbalance, advocates must connect with reporters before there is a report to release or a story to pitch. Cold calls are rarely as effective as pitches sent to people who know and trust you. These relationships take time to cultivate, but you can begin by mapping the media environment where you live. Follow coverage closely and see who is already reporting on racial equity issues. Who is discussing affordable housing but not making the link to Latinos? Who is discussing Latino culture and traditions in human interest stories but not connecting the dots back to policy? Are there smaller, regional outlets in areas with large Latino populations that might be interested in this intersection? You can think of this as a listening dashboard and a starting point for future shifts in coverage.

Train Latino spokespeople.

It is important for the communities most affected by an issue to be the ones to tell their own stories — to see their voices reflected back to them in the news. Yet only 14% of articles explicitly identified speakers as Latino. Media training can help people with lived experience be powerful “authentic voices” who can talk both about their own stories as well as what should be done to ensure that no one else has to suffer. By putting authentic voices forward for media opportunities, advocates are helping to keep storytelling power within the community. This approach also helps to move coverage away from reductive stereotypes toward more accurate, nuanced portrayals. With proper training, effective spokespeople can:

- Tell stories that combine data with lived experience. Statistics alone are not enough to change hearts and minds; they must be rooted in real-world examples.

- Highlight community strengths, not just weaknesses. Although we have to know a problem exists to address it, trained spokespeople can help ensure that their communities are not portrayed exclusively as victims but also as agents of change. This opens audiences to understanding — and embracing as possible — various solutions.

It is important, however, to avoid approaching potential spokespeople with an extractive or transactional lens. While sharing deeply personal stories can be empowering and cathartic for some people, it can feel triggering or retraumatizing for others. The Center for Journalism Ethics has guidance for connecting with sources in less transactional ways; these can be helpful for advocates and journalists alike.

Conclusion

Our findings highlight deficits in the public discourse about Latinos — deficits that are problematic because they may limit how Latinos and their contributions are understood not only by newspaper readers, but also by policymakers, business leaders, and others whose choices may affect the course of our nation. It is simply not possible to fully understand the issues facing our country if the experiences and perspectives of our second largest ethnic group are excluded from the news. Our findings highlight the need for and promise of more diverse and inclusive newsrooms that elevate the voices of the communities they serve — and, in turn, help paint a clearer, more complete picture of the United States.

Acknowledgments

This report was authored by media researchers Kim Garcia, MPH, and Sarah Perez-Sanz, MPH; Head of Research, Pamela Mejia, MPH, MS; and Senior Manager of Communication and Digital Strategy, Heather Gehlert, MJ.

Many thanks to UnidosUS staff Charles Kamasaki, senior cabinet advisor; Viviana López Green, Esq., senior director, Racial Equity Initiative; and Clarissa Martinez de Castro, vice president of the Latino Vote Initiative, for their valuable assistance during the analysis phase of the study and substantive feedback to the report.

Thanks also to David Castro, deputy vice president of communications and marketing at UnidosUS; Kristina Villavicencio, marketing and events specialist at UnidosUS; Elsa Rainey, director of public affairs and communications at GPS IMPACT; and Brandie Campbell, press and outreach specialist at Public Health Institute, for their support with strategic communications and dissemination.

This research report was made possible through the support of the UnidosUS Racial Equity Initiative (REI) funders. UnidosUS’s REI aims to reposition the Latino community’s contributions to and presence in the public discourse as an essential element of a strategy to advance Latino equity in our multiracial society. The views and conclusions expressed here are those of BMSG and UnidosUS alone and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of UnidosUS’s funders.

Endnote

Click the above heading "endnote" to return to its corresponding location within the report text.

The term “Latino” is used interchangeably with “Hispanic” by the U.S. Census Bureau. We use the term “Latino” in this document to refer to persons of Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, Central and South American, Dominican, Spanish, and other Hispanic descent. According to the technical definitions used by the Census, Latinos may be of any race. This document uses the sociological construct of “race,” whereby, at least historically, most Latinos were treated as a distinct racial group, regardless of ethnicity. UnidosUS also occasionally refers to this population as “Latinx” to represent the diversity of gender identities and expressions that are present in the community.

References

Click the number to the left of each reference to be taken back to its corresponding location within the report text.

1. Foster-Frau S. Latinos are disproportionately killed by police but often left out of the debate about brutality, some advocates say. The Washington Post. Published June 2, 2021 at https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/police-killings-latinos/2021/05/31/657bb7be-b4d4-11eb-a980-a60af976ed44_story.html. Accessed March 14, 2023.

2. Mejia B, Vives R. More L.A. Latinos falling into homelessness, shaking communities in “a moment of crisis.” Los Angeles Times. Published October 28, 2022 at https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2022-10-28/rising-homelessness-in-the-latino-community. Accessed March 14, 2023.

3. Scherer Z, Yerís Mayol-García. Half of people of Dominican and Salvadoran origin experienced material hardship in 2020. Census.gov. Published September 28, 2022 at https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2022/09/hardships-wealth-disparities-across-hispanic-groups.html. Accessed March 14, 2023.

4. McCombs M, Shaw D. The agenda-setting function of mass media. Public Opinion Quarterly. 1972;36:176-187. doi:10.1086/267990

5. Dearing JW, Rogers EM. Agenda-Setting. Sage; 1996.

6. Scheufele D, Tewksbury D. Framing, agenda setting, and priming: The evolution of three media effects models. Journal of Communication. 2007;57(1):9-20.

7. Torres J, Bell A, Watson C, Chappell T, Hardiman D, & Pierce C. Media 2070: An invitation to dream up media reparations. Published online 2020 at https://mediareparations.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/media-2070.pdf. Accessed March 14, 2023.

8. Gottfried J, Mitchell A, Jurkowitz M, Liedke M. Journalists give industry mixed reviews on newsroom diversity, lowest marks in racial and ethnic diversity. Pew Research Center. Published June 14, 2022 at https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/2022/06/14/journalists-give-industry-mixed-reviews-on-newsroom-diversity-lowest-marks-in-racial-and-ethnic-diversity/. Accessed March 14, 2023.

9. U. S. Government Accountability Office. Hispanic underrepresentation in the media. WatchBlog. Published September 23, 2021 at https://www.gao.gov/blog/hispanic-underrepresentation-media. Accessed March 14, 2023.

10. Bourgault J. Diversity in the newsroom can build better media. Here’s why. World Economic Forum. Published December 1, 2021 at https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/12/diversity-in-news-media/. Accessed March 14, 2023.

11. Tameez H. The Philadelphia Inquirer’s journalists of color are taking a “sick and tired day” after “Buildings Matter, Too” headline. Nieman Lab. Published June 4, 2020 at https://www.niemanlab.org/2020/06/the-philadelphia-inquirers-journalists-of-color-are-taking-a-sick-and-tired-day-after-buildings-matter-too-headline/. Accessed March 14, 2023.

12. Flynn K. Journalists of color are fed up and speaking out. CNN. Published June 5, 2020 at https://www.cnn.com/2020/06/05/media/journalists-diversity/index.html. Accessed March 14, 2023.

13. Green VL, Poppe SV. Toward a more perfect union: Understanding systemic racism and resulting inequity in Latino communities. UnidosUS; 2021:40. https://unidosus.org/publications/2128-toward-a-more-perfect-union-understanding-systemic-racism-and-resulting-inequity-in-latino-communities/. Accessed March 14, 2023.

14. Delia Deckard N, Browne I, Rodriguez C, Martinez-Cola M, Gonzalez Leal S. Controlling images of immigrants in the mainstream and Black press: The discursive power of the “illegal Latino.” Lat Stud. 2020;18(4):581-602. doi:10.1057/s41276-020-00274-4

15. Wei K, Booth J, Fusco R. Cognitive and Emotional Outcomes of Latino Threat Narratives in News Media: An Exploratory Study. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research. 2019;10(2):213-236. doi:10.1086/703265

16. Silber Mohamed H, Farris EM. ‘Bad hombres’? An examination of identities in U.S. media coverage of immigration. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. 2020;46(1):158-176. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2019.1574221

17. United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey Data: 2021 1-Year Estimates Data Profiles. ACS Demographic and Housing Estimates. Published 2021. https://data.census.gov/table?q=DP05. Accessed March 14, 2023.

18. McManus J, Dorfman L. Issue 9: Youth and Violence in California Newspapers. Berkeley Media Studies Group; 2000:16. http://www.bmsg.org/resources/publications/issue-9-youth-and-violence-in-california-newspapers. Accessed March 14, 2023.

19. Genn A. Journey for equity. Long Island Business News. Published August 5, 2022 at https://libn.com/2022/08/05/journey-for-equity/. Accessed March 14, 2023.

20. Shelbourne T. Despite $37M spent on homeownership programs, Black and Hispanic homeowner rates remain low, report says. Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Published July 26, 2022 at https://www.jsonline.com/story/news/local/milwaukee/2022/07/26/despite-37-m-homeowner-programs-low-black-hispanic-rates-persist/10115660002/. Accessed March 14, 2023.

21. Sippio-Smith TA. 4 ways Tom Wolf can improve racial equity in Pa. schools | Opinion. The Philadelphia Inquirer. Published May 17, 2022. https://www.inquirer.com/opinion/brown-v-board-of-education-pennsylvania-schools-equity-20220517.html. Accessed March 14, 2023.

22. Dorfman L, Herbert S. Engaging reporters to advance health policy. The California Endowment; 2007:56. https://www.bmsg.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/tce-bmsg-c4c-mod5-engaging-reporters.pdf. Accessed March 14, 2023.

23. Martin J, Gomez Licon A, Tang T. Baby formula shortage highlights racial disparities. The Associated Press. Published May 27, 2022 at https://apnews.com/article/covid-health-united-states-bdc079e51ae6241dce2f78533a055b3a. Accessed March 14, 2023.

24. Flores J. S.F. transgender Lutheran bishop resigns amid controversy over removal of pastor. San Francisco Chronicle. Published June 6, 2022 at https://www.sfchronicle.com/sf/article/S-F-transgender-Lutheran-bishop-resigns-amid-17223465.php. Accessed March 14, 2023.

25. Hilton A, DuClos D. Our classrooms are increasingly diverse, yet 9 of 10 teachers are white. Why that’s a problem and what can be done about it. Post Crescent. Published September 12, 2022 at https://www.postcrescent.com/story/news/education/2022/09/12/wisconsin-student-diversity-grows-schools-face-few-teachers-color/10309228002/. Accessed March 14, 2023.

26. Cohen H, Ocner M. Bans Off Our Bodies rally draws thousands, including candidates, to Miami-Dade park. The Miami Herald. Published May 14, 2022 at https://www.miamiherald.com/news/politics-government/state-politics/article261430382.html. Accessed March 14, 2023.

27. Guerrero B. Health council to aid Hispanic community. Gaston Gazette. Published June 4, 2022 at https://www.gastongazette.com/story/news/2022/05/24/gaston-county-council-provides-health-hispanic-community/7355521001/. Accessed March 14, 2023.

28. “This Changes Everything”: Geena Davis on empowering women in Hollywood. Fresh Air. Published online August 7, 2019. https://www.npr.org/2019/08/07/749067994/this-changes-everything-geena-davis-on-empowering-women-in-hollywood. Accessed March 14, 2023.

29. Meyer M, Conroy M. #SeeItBeIt: What children are seeing on TV. The Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media; 2022:54. https://seejane.org/wp-content/uploads/GDI-See-It-Be-It-TV-2022-Report-v2.pdf. Accessed March 14, 2023.

30. Rothman M. Study reports children’s television reaches gender equality; other media still has work to do. Good Morning America. Published September 25, 2019 at https://www.goodmorningamerica.com/culture/story/study-reports-childrens-television-reaches-gender-equality-media-65817980. Accessed March 14, 2023.

31. Bauder D. Efforts to track diversity in journalism are lagging. The Associated Press. Published October 14, 2021 at https://apnews.com/article/business-race-and-ethnicity-journalism-arts-and-entertainment-885ce3486382d7c3080519c50407aa18. Accessed March 14, 2023.

32. Race-class: Our progressive narrative. Dēmos; 2018. https://www.demos.org/research/race-class-our-progressive-narrative. Accessed March 14, 2023.

33. The American Election Eve Poll. Latino voters in the 2020 election: National survey results. Presented November 5, 2020. https://unidosus.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/unidosus_latinodecisions_latinovotersinthe2020election.pdf. Accessed March 14, 2023.

Appendix A: Methods

BMSG collected articles published between May 1 and September 30 in 2020, 2021, and 2022.

We used LexisNexis, a database of print and online news publications, to search for articles from around the United States. With input from UnidosUS, BMSG developed search terms to cast a wide net for articles related to racism and racial equity (including, for example, “inequity,” “police violence,” “wealth gap,” “housing gap,” etc.). We then identified two pools of articles:

- News about racial equity: We identified news about racial justice, racism, and equity issues by searching for articles that used terms like “inequity,” “police violence,” “wealth gap,” and “housing gap.”

- News about racial equity and Latinos: We identified news about racial equity that also included at least one variation of a term like “Hispanic,” “Latino/a/x/e,” or country-specific terms accounting for all countries in Central and South America (such as “Mexican,” or “Brazilian”).

For stories from Category 2, we refined our search terms to ensure that references to Latinos appeared within the same paragraph as terms related to racism and racial equity.

We also used ProQuest, a database of research and news publications, to collect articles in categories 1 and 2 from The Washington Post, an outlet that is not available on LexisNexis. Due to ProQuest’s limited search operators, we were unable to replicate the exact same search parameters; specifically, we were unable to ensure that, for stories in Category 2, Latino terms appeared near racism and racial equity terms in the text. Consequently, the volume of racial equity news and proportion of news that referenced Latinos from The Washington Post may be inflated.

Quantitative analysis

BMSG collected the metadata of all articles published in 2020, 2021, and 2022 to compare news about racial equity (Category 1) to news about racial equity and Latinos (Category 2). We used descriptive analysis to assess variables like:

- the volume of coverage by year,

- the outlets in which articles were published,

- the geographic distribution of stories.

Qualitative analysis

To evaluate how Latinos were portrayed in news about racism and racial equity, we conducted an ethnographic content analysis of a generalizable sample of 4% of articles from Category 2. To ensure that our analysis centered on the most current stories, we limited our sample to articles published during the 2022 sample period (n=69 articles).

We developed and tested coding variables and discussed any disagreements to establish consensus between coders and to refine the coding instrument. We excluded stories that did not discuss racism or racial equity or made only very brief, passing mentions of Latino communities; we also excluded international news. Our final sample included 62 relevant articles.

We used qualitative analysis software ATLAS.ti to code and analyze our data. Specifically, we:

- Evaluated each news article to assess what the stories were about (drawing on UnidosUS’ work on systemic racism), and how they characterized problems facing — and solutions supporting — Latino communities.

- Documented the presence and portrayal of Latino individuals, communities, and organizations by searching the text of each story to capture the different descriptions of Latinos in articles — whether authors used terms such as “Hispanic,” “Latino/a,” “Latinx/e,” “Afro-Latino/a,” or “Spanish-speaking.” We coded more specific descriptions by ethnicity, nationality (i.e. place of birth), or migrant status.

- Assessed who spoke in the news and evaluated whether those speakers could be identified as Latino using the following criteria:

- explicit identification based on descriptions in the article or self-identification by speakers themselves (e.g. “She says she identifies as Afro-Latina,” “ a Salvadoran immigrant”);

- implicit identification using a list of common Hispanic names for reference. We recognize this is an imperfect indicator of whether or not a person is Latino.

There may be speakers who identify as Latino who were not explicitly identified as such in the article, or were not presumed to be Latino by our coders. Additionally, individuals could adopt a name commonly understood to be Latino (e.g., through marriage).

Appendix B: Presumably Latino authors of news articles about racial equity that referenced Latinos

From our qualitative analysis, we did not find any authors or bylines who were explicitly identified or described as Latino (see Appendix A). We categorized the following authors as implicitly identified, or “apparently Latino,” based on their names:

- Daniel Gonzalez: “Afro-Latinos often face the question, 'What are you?’: Why these Arizonans are embracing their blackness,” The Arizona Republic

- Matias Ocner: “Bans Off Our Bodies rally draws thousands, including candidates, to Miami-Dade park,” The Miami Herald

- Lori Rozsa: “DeSantis flexes his influence with 'anti-woke' school board victories,” The Washington Post

- Adriana Gomez Licon: “Formula shortage shows disparities Black, Hispanic women facing a variety of hurdles,” The Baltimore Sun

- Ricardo Cano: “New data shows shift at Lowell High School: More students given failing grades after admissions change,” San Francisco Chronicle

- Jessica Flores: “S.F. transgender Lutheran bishop resigns amid controversy over removal of pastor,” San Francisco Chronicle

- Albert Serna: “'An excuse to racially profile': How Florida trains police on bias,” Tampa Bay Times

- Cara Murez: “Experiences of racism tied to worsening memory, thinking in older Black Americans,” The Breeze: James Madison University (Harrisonburg, Virginia)

- Beatriz Guerrero: “Health council to aid Hispanic community,” The Gaston Gazette (North Carolina)

Appendix C: Authors who most often wrote about Latinos in news about racial equity

The reporters who most often wrote stories that mentioned both Latinos and racial equity issues were:

- Aaron Morrison, Dayton Daily News, Winston-Salem Journal, and other outlets across the U.S. (71 articles)

- Aaron Eaton, The Philadelphia Tribune (52)

- Jerry Nowicki, Star-Courier, The Daily Leader, and other Illinois-based outlets (39)

- Carla K. Johnson, Post & Courier, The Houston Chronicle, and other outlets across the U.S. (38)

- Alex Putterman, The New Canaan Advertiser, The Hartford Courant, and other Connecticut-based outlets (25)

- Cameron Sheppard, Auburn Reporter, Federal Way Mirror, and other Washington-based outlets (24)

- Dan Walters, CALMatters, The Mercury News, and other California-based outlets (23)

- Elaine Gross, Baldwin Herald, Nassau Herald, and other New York-based outlets (21)

- Emma Simmons, CBS, NBC (21)

- Irv Randolph, The Philadelphia Tribune (21)