The new age of food marketing: How companies are targeting and luring our kids — and what advocates can do about it

Saturday, October 01, 2011Marketing has long been a feature of our daily landscape. But the explosion of digital culture in recent years has dramatically changed the playing field and the rules, especially for children and teenagers, and companies marketing fast food, snack food, and soft drinks are at the forefront of the game.

Young people's relationship with media is no longer limited to the passive, one-sided consumption of TV commercials, print ads, and the like. Now our kids are interacting with brands and products every day, often unwittingly inviting marketers to connect with them and their friends online. Marketers are carefully tracking teens online and by cell phone, mining conversations on Facebook and Twitter, collecting data to develop and record personalized behavioral profiles, and more.

The traditional marketing paradigm is spinning into an unprecedented new world, as fast food, snack, and beverage companies draw from an expanding toolbox of sophisticated online and social marketing techniques.1,2 Today, powerful and intense promotions are completely, seamlessly integrated into young people's social relationships and minute-by-minute interactions.

Why should health advocates be concerned about the new marketing paradigm? Because young people's choices about what to eat and when are largely shaped by food and beverage marketing — and these industries are now reaching our kids through a multitude of interactive devices and platforms, pushing products onto young consumers who lack the information and capacity to understand the consequences of an impulsive decision.3, 4

Food and beverage marketing to children in America represents a direct threat to the health prospects of the next generation.5 Now more than ever, children in the United States are growing up in environments saturated with marketing for fast food, snacks, and sugary beverages. Today, one in three teens is either overweight or obese, and overweight young people are likely to stay overweight throughout their lives, which puts them at higher risk for serious and even life-threatening health problems.

Teenagers are an obvious prime audience for digital marketing strategies, given their avid use of mobile phones, media players, blogs, online video channels, social networks such as Facebook and Twitter, and other digital media platforms and devices. And they're especially vulnerable to food and beverage marketers' tactics: The teen years are a critical developmental period when consumer and eating behaviors are established that may well last throughout an individual's lifetime.6, 7

What's more, growing research suggests that biological and psychosocial attributes of the adolescent experience may play an important role in making teens more vulnerable to marketing.8, 9 Research on brain development, for example, has found that the prefrontal cortex — which controls inhibition — may not fully mature until early adulthood.10, 11 ,12, 13 Meanwhile, children entering puberty experience hormonal changes that make them more receptive to environmental stimuli.

In other words, at the time in their lives when their biological urges are particularly intense, adolescents have not yet acquired the ability to control these urges. Researchers suggest that these innate factors are likely to make teens more susceptible to advertising, especially when they are distracted, exposed to high-level stimuli, or subjected to peer pressure — all hallmarks of digital marketing tactics.14

The impact of food marketing on ethnic minority youth is a particular concern. Obesity rates are significantly higher for African-American girls and Hispanic boys than for whites, and ethnic youth are targeted aggressively by the food, beverage, and fast food industries. Research shows that ethnic minority youth are more interested in, positive toward, and influenced by marketing than non-Hispanic whites.15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 A research group backed by McDonald's, Kraft, PepsiCo, Burger King, and others calls Hispanics "the most important U.S. demographic growth driver in the food, beverage, and restaurant sectors."21 And African-Americans and Hispanics are more likely than "general market" consumers to use social networking spaces to share opinions with friends about products, services, and brands, according to a column in Advertising Age.22 Driven by the growing number of ethnic youth, as well as by their heavy use of new media and cultural trendsetting, digital marketers have made understanding and connecting with ethnic youth a priority.

Of all the tactics fast food, snack food, and soft drink companies routinely use to target children and adolescents, many fall into five broad categories:

1 Creating immersive environments

2 Infiltrating social networks

3 Location-based and mobile marketing

4 Collecting personal data

5 Studying and triggering the subconscious

This report provides a brief snapshot of these five categories. You can also download additional details and visual examples of these tactics at http://case-studies.digitalads.org to explore them firsthand — from Mountain Dew's use of social networks as a low-cost way of developing and promoting new products to Doritos' elaborate campaign to revive a failing product. But these examples are only the beginning.

1. Creating immersive environments

State-of-the-art animation, high-definition video, and other multimedia applications are spawning a new generation of three-dimensional experiences. In these immersive virtual environments, through the use of avatars and other first-person simulations, teens are surrounded by powerful images and sounds, plunged into the center of the action.

Immersive marketing techniques routinely integrate advertising and other content in such a way as to make the two indistinguishable.23 In a virtual world, marketers can seamlessly incorporate their products, fostering an emotional relationship between the consumer and the brand. The immersive experience is designed to circumvent the user's conscious process of evaluating a product's attributes, eliciting an automatic response that makes the user more susceptible to promotions.

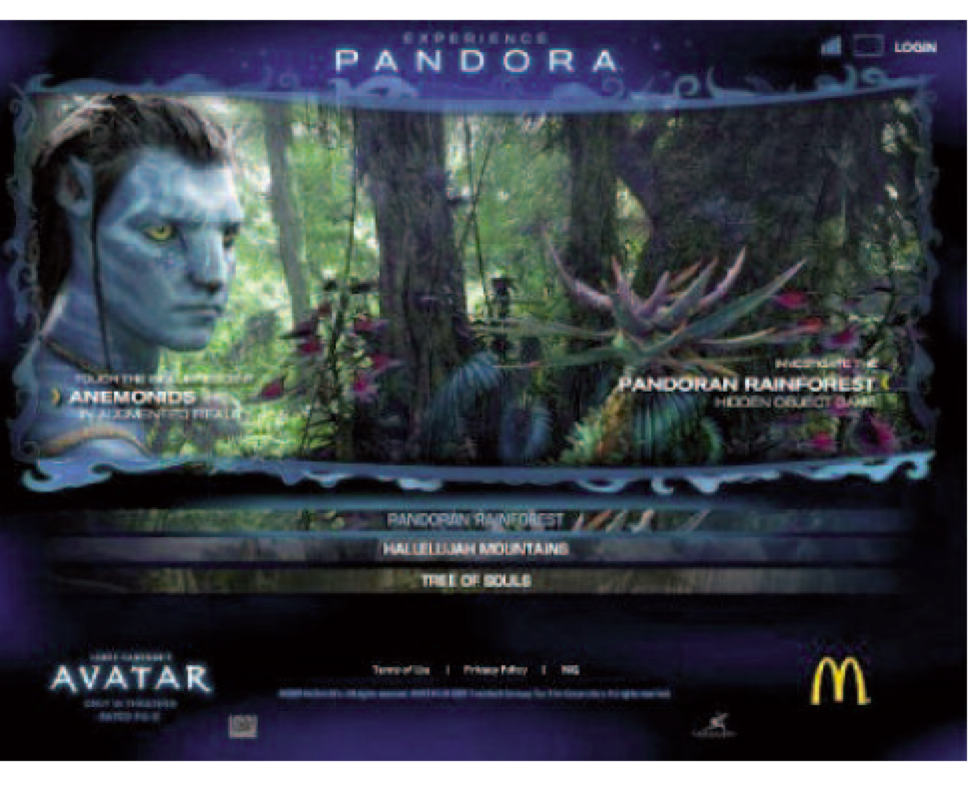

McDonald's, for example, used virtual reality technology to appeal to young consumers through its ambitious tie-in with the film Avatar: Young people could log on to the McDonald's Avatar site and use a webcam to interact with a variety of augmented reality games.24 The goal of the campaign, as reported in Variety magazine: to promote its Big Mac to young adults and to entice kids to request more Happy Meals.25 Buying Big Macs gave consumers a way to reach higher levels of game play, and codes placed inside Happy Meals gave children access to special features on the website. The strategy worked: According to the Promotion Marketing Association, McDonald's saw an 18 percent increase in Big Mac sales in the United States as a result of the campaign.26

2. Infiltrating social networks

Online social media like Facebook and YouTube are among the most popular digital media platforms for teens,27 and they provide an easy opportunity for marketers to access and exploit an individual's web of social relationships. Using a host of new techniques and tools, social media marketers can observe and insert themselves into online social interactions to influence the conversation.

Marketers also frequently tempt young people with a variety of incentives — contests, prizes, free products — to participate in viral marketing campaigns by circulating brand-related content, often generated by the users themselves. Social networks add the element of peer influence to what is already a powerful marketing appeal, targeting adolescents at a point in their lives when they look to friends as models of what types of behavior to pursue.

Mountain Dew, for example, launched a viral marketing campaign dubbed "DEWmocracy," using a variety of social network platforms to get young people involved in choosing and promoting a new product. Fans registered at DEWmocracy.com and urged their friends and social media followers to vote on the look and taste of a new soft drink. A marketing trade publication reports that soon after the campaign launched, Mountain Dew ranked first on tweens' list of "Newest Beverages" they had tried.28

In 2009, the company launched the second phase of the campaign with DEW Labs, a private social network for the brand's most fervent supporters, using exclusivity to get fans to promote the product. "Once you get the invite, you're not necessarily in," one enthusiastic blogger and DEW Labs "member" explained. "Mountain Dew is looking for a particular type of Dew fan an uber fan, a fan that goes the extra mile for their Mountain Dew." The blogger went on to quote a company executive's characterization of DEW Labs members as "passionate not just [as] in 'I love this brand,' but 'I want to talk about it it's a part of my everyday'; 'I eat, drink, sleep Mountain Dew.' It represents who they are."29

3. Location-based and mobile marketing

Young people in particular rely on mobile devices for a growing number of services: phone, web and social network access, maps and directions, entertainment, and more. The ubiquity of mobile phones gives marketers the unprecedented ability to follow young people throughout their daily lives, delivering enticing marketing offers that are designed to elicit impulsive behaviors. New forms of loyalty-based programs reward consumers when they "check in" at a restaurant with their mobile phone. And cravings can now be easily triggered at the exact point when a teen is near a fastfood restaurant, made even more irresistible through a variety of incentives such as coupons, discounts, and free offers.

Mobile marketers offer advertisers an array of ways to target consumers based on where they are and what they're doing at any moment. Brightkite, a startup with offices in California and Finland, promotes these targeting capabilities, among others:

- Location and place targeting: "We can target by precise geography — people in Tulsa, people within two miles of a KFC, people at Costco."

- Real-world behavioral targeting: "Want to target people who buy [certain items] more than three times a week? We know who they are."

- Time of day: "We know where our members are and the time zone of their location. With this information, you can deliver messages that are time sensitive — the lunch rush, etc."

- Weather: "We know the location of our millions of users, and we also know the precise weather in each location. Example: Diet Coke wanted to target people when the afternoon temperature was over 75 degrees."*

4. Collecting personal data

Data collection is at the core of contemporary digital marketing for many of the leading food and beverage companies, from Coca-Cola and PepsiCo to McDonald's and other fast food outlets. Consumers are tagged with unique identifiers when they go online, and tracked, profiled, and targeted for personalized marketing and advertising as they navigate the Internet. Powerful analytical software mines data from new media applications and analyzes patterns of user behavior to help craft and refine marketing strategies.

Marketers argue that the data they collect are not "personally identifiable," but there is growing evidence from around the world that the distinctions between what is considered personally identifiable (such as a person's name and email address) and "nonpersonal" information (such as cookies and invisible data files) are outmoded and need to be revised.30

Coca-Cola's MyCokeRewards program is one example of a loyalty marketing program that prompts users to provide personalized data to participate, collecting the information to help shape and target its marketing. To win contest prizes and rewards, consumers must create an account at MyCokeRewards.com, where they can then enter codes from bottle caps and cartons; each visit to the site supplies marketers with "demographic and psychographic details."31 As one consumer analysis firm describes, this gives Coca-Cola "mountains of data" it can use to "personalize the look and messaging of a particular web page, email or mobile content, or send an exclusive offer."32, 33 By 2009, some 285,000 users were entering, on average, seven codes per second on MyCokeRewards.com.34

"We're especially targeting a teen or young adult audience," Carol Kruse, the Coca- Cola executive responsible for MyCokeRewards, told a marketing trade magazine. "They're always on their mobile phones and they spend an inordinate amount of time on the Internet . We did some online consumer studies with Yahoo! and Nielsen [determining that] yes, indeed, an online ad unit can make an emotional connection and encourage consumers to buy more of our products."35

5. Studying and triggering the subconscious

Since 2005, the advertising industry has expanded its use of the latest techniques developed by neuroscientists conducting brain research. "Neuromarketing," as it is called, is now a critical component of the industry's digital marketing research and development efforts, and a key strategy for fostering brand engagement.36,37 Companies are perfecting the use of biosensory tools — including functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), electroencephalography (EEG), and eye-tracking technologies — to aid advertisers in designing marketing campaigns and measuring consumer response to marketing messages and techniques.

By harnessing the tools of neuroscience, marketers can fine-tune their strategies to trigger instantaneous responses at a subconscious level, creating more likelihood that consumers — especially young people — will engage in impulsive behaviors. The direct goal of neuromarketing is to circumvent rational decision making, which is especially troubling when used to market unhealthy foods. While advertisers have a long tradition of practices designed to tap into unconscious processes, neuromarketing constitutes a significant leap into disturbing new territory.

PepsiCo's Frito-Lay, for example, used neuromarketing to expand the reach of and increase total sales for its billion-dollar brand, Cheetos.38 Long known as a kids' snack, PepsiCo aimed to reposition the brand for adults after signing the 2007 voluntary Children's Food & Beverage Advertising Initiative, which restricts advertising to children under 12. Though the company wanted to target adults in this instance, they penetrated kids minds to do so. Researchers recruited Cheetos consumers, including children ages 10-13, in a study to uncover the thoughts and emotions connected to the brand. An additional study also looked at participants' brain activity to learn more about the experience of eating Cheetos without having to rely on people's self-reports of why they liked the product.39

Marketers then used insights from the research to develop "Orange Underground," a TV and Internet ad campaign for their new audience. But the company's use of neuro techniques didn't stop there: Researchers also used a process known as facial coding to access viewers' subconscious responses to the new ads. In bypassing the conscious mind, marketers learned that responses to the ads were much more positive than people admitted when asked for their opinion.40 From a marketing perspective, the campaign was a success, winning the U.S. ad industry's highest research honors: the Grand Ogilvy.41, 42

Digital marketing practices are already in widespread use. Given the enormous financial resources food and beverage marketers are devoting to them, and the ubiquity of multimedia devices among teens, it may seem futile to try to stem the influence. How can we protect our kids from harmful marketing tactics without compromising their ability to participate in contemporary media culture?

With growing concern among policymakers and researchers about the national obesity crisis, as well as a growing desire to safeguard children's privacy online, advocates can capitalize on the momentum to help push for policy and research interventions. Government and industry need to ensure that digital marketing campaigns are designed and carried out in ways that treat young people fairly, with special consideration for adolescents' developmental vulnerabilities and needs. And researchers concerned about the impact of food marketing on young people must expand their work to consider the nature and scope of these new practices.

Several national groups are already working to advance change on this issue, monitoring problematic marketing campaigns and filing complaints with federal authorities where appropriate:

The Food Marketing Workgroup (www.foodmarketing.org) is a national collaborative of leaders in nutrition, public health, advertising/ marketing, consumer protection, public policy, child development, and government working to identify and investigate practices that lead to unhealthy diets and lifestyles for young people. The FMW is convened by the Berkeley Media Studies Group and the Center for Science in the Public Interest (www.cspinet.org).

The National Policy & Legal Analysis Network to Prevent Childhood Obesity (NPLAN) works with communities throughout the country to create and implement strong obesity prevention policy interventions. NPLAN (www.nplanonline.org), funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, also provides input to federal policymakers on nutrition and physical activity issues, including food marketing to children.

The Center for Digital Democracy (www.democraticmedia.org) works to inform consumers, policymakers, and the press about contemporary digital marketing issues, including its impact on public health.

Advocates can join with these organizations to help identify and report campaigns that violate federal laws against deceptive and unfair marketing practices.

For more information about the kinds of activities federal authorities have deemed deceptive or unfair, and the process for bringing a matter to the government's attention, NPLAN has developed several publications specifically for advocates:

Identifying and Reporting Unfair, Misleading, and Deceptive Ads and Marketing

State Attorneys General: Allies in Obesity Prevention (a series of fact sheets)

Finally, advocates can help galvanize public support for change by spreading awareness about the marketing practices outlined in this report. Drawing media attention to these issues, educating congressional representatives about the ways in which children are targeted, and creating opportunities for young people to educate their peers about digital marketing and its relationship to health are critical for shining a light on the impact of these tactics and building momentum for change.

New digital marketing tactics are emerging and advancing rapidly, and it's crucial to begin establishing standards and policies to protect the health of future generations. With new techniques for data collection, monitoring, profiling, and targeting rolled out almost daily, we have an urgent responsibility — and only a brief window of opportunity — to intervene.

* Brightkite. Advertise with us: Ultra-targeted advertising. Retrieved February 23, 2011 from http://brightkite.com/pages/bk_ad_targeting_capabilities.html.

This report was designed to provide a general introduction to the food and beverage industry's use of digital marketing to target children and adolescents. It summarizes findings from the following:

Kathryn Montgomery, Sonya Grier, Jeff Chester, and Lori Dorfman. "Food Marketing in the Digital Age: A conceptual framework and agenda for research." Research supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation's Healthy Eating Research program.

Kathryn Montgomery and Jeff Chester. "Digital Food Marketing to Children and Adolescents: Problematic Practices and Policy Interventions." Prepared for the National Policy & Legal Analysis Network to Prevent Childhood Obesity. All reports are available from http://digitalads.org/reports.php

For a more in-depth look at these issues, along with specific research and regulatory recommendations, see additional reports and more at www.digitalads.org. For examples of the campaigns described in this report, see http://case-studies.digitalads.org/

© 2011, Center for Digital Democracy, Public Health Law & Policy, and Berkeley Media Studies Group, a project of the Public Health Institute

References

1 Montgomery K.C., and Chester J. (2009). Interactive Food and Beverage Marketing: Targeting Adolescents in the Digital Age. Journal of Adolescent Health, 45, S18-S29.

2 Chester J., and Montgomery K.C. (2007, May). Interactive Food and Beverage Marketing: Targeting Youth in the Digital Age. Berkley, CA: Berkeley Media Studies Group. Retrieved June 20, 2011 from http://www.digitalads.org/documents/digiMarketingFull.pdf.

3 Institute of Medicine. (2005, December 6). Food Marketing to Children and Youth: Threat or Opportunity? Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press.

4 Pechmann, C., Levine, L., Loughlin, S., et al. (2005). Impulsive and Self-Conscious: Adolescents' Vulnerability to Advertising and Promotion. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 24(2), 202-221.

5 Institute of Medicine. (2005, December 6). Food Marketing.

6 Brownell, K., Schwartz, M., Puhl, R., Henderson, K., and Harris, J. (2009, September). The Need for Bold Action to Prevent Adolescent Obesity. Journal of Adolescent Health, 45(3), S8-S17.

7 Story, M., Sallis, J., and Orleans, T. (2009, September). Adolescent Obesity: Towards Evidence-Based Policy and Environmental Solutions. Journal of Adolescent Health, 45(3), S1-S5.

8 Pechmann et al. (2005). Impulsive and Self-Conscious.

9 Leslie, F., Levine, L., Loughlin, S., Pechmann, C. (2009, June 29-30). Adolescents' Psychological & Neurobiological Development: Implications for Digital Marketing. Memo prepared for the Second NPLAN/BMSG Meeting on Digital Media and Marketing to Children for the NPLAN Marketing to Children Learning Community, Berkeley, CA. Retrieved June 13, 2011 from http://digitalads.org/documents/Leslie_et_al_NPLAN_BMSG_memo.pdf.

10 Giedd, J. (2008). The Teen Brain: Insights from Neuroimaging. Journal of Adolescent Health, 42(4), 335-343.

11 McAnarney, E.R. (2008). Adolescent Brain Development: Forging New Links? Journal of Adolescent Health, 42(4), 321-323.

12 Steinberg, L. (2007). Risk Taking in Adolescence: New Perspectives from Brain and Behavioral Science. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(2), 55-59.

13 Steinberg, L. (2008). A Social Neuroscience Perspective on Adolescent Risk-taking. Developmental Review, 28(1), 78-106.

14 Leslie et al. (2009, June 29-30). Adolescents' Psychological & Neurobiological Development.

15 Bush, A., Smith, R., and Martin, C. (1999). The Influence of Consumer Socialization Variables on Attitude toward Advertising: A Comparison of African-Americans and Caucasians. Journal of Advertising, 28(3), 13-24.

16 Korzenny, F., Korzenny, B., McGavock, H., and Inglessis M.G. (2006). The Multicultural Marketing Equation: Media, Attitudes, Brands, and Spending. Center for Hispanic Marketing Communication, Florida State University.

17 Moschis, G. (1987). Consumer Socialization: A Life-Cycle Perspective. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

18 Singh, N., Kwon, I., and Pereira, A. (2003). Cross-Cultural Consumer Socialization: An Exploratory Study of Socialization Influences across Three Ethnic Groups. Psychology & Marketing, 20(10), 15.

19 Stroman, C. (1991). Television's Role in the Socialization of African American Children and Adolescents. The Journal of Negro Education, 60(3), 314-27.

20 Woods, G.B. (1995). Advertising and Marketing to the New Majority. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company.

21 Latinum Network. (2010, April 8). U.S. Hispanics Propel Real Growth in Food, Beverage and Restaurant Sectors, According To Latinum Network. Retrieved June 13, 2001 from www.latinumnetwork.com/release4.php.

22 Huang, C. (2009, September 8). What Social Media Can Learn from Multicultural Marketing. Advertising Age. Retrieved June 13, 2011 from http://adage.com/bigtent/post?article_id=138864.

23 Hoffman, D., and Novak, T. (1996, July). Marketing in Hypermedia Computer-Mediated Environments: Conceptual Foundations. The Journal of Marketing, 60(3), 50-68.

24 McDonald's Brings Customers to Another Planet in Partnership with James Cameron's Movie Masterpiece 'Avatar'. (2009, December 10). Retrieved August 3, 2010 from http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/mcdonalds-brings-customers-to-another-planet-in-partnership-with-james-camerons-movie-masterpiece-avatar-78966417.html.

25 Graser, M. (2009, November 19). 'Avatar' Toys with Augmented Reality. Variety. Retrieved August 3, 2010 from http://www.variety.com/article/VR1118011632?refCatId=13.

26 Promotion Marketing Association. 2010 REGGIE Awards: McDonald's Avatar Program. Retrieved August 5, 2010 from http://www.omnicontests3.com/pma_reggie_awards/omnigallery/entry/gallery_item_info.cfm?ch ild=1&client_id=1&entry_id=312&competition_id=1&entrant_id=97&gallery_item_id=135.

27 Rideout V.J., Foehr U.G., and Roberts D.F. (2010). Generation M2: Media in the Lives of 8-18 Year Olds. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation. Retrieved June 20, 2011 from http://www.kff.org/entmedia/upload/8010.pdf.

28 Lentini, N. (2009, April 1). Cross-Media Case Study: Plugged in to the Electorate. OMMA Magazine. Retrieved August 7, 2010 from www.mediapost.com/publications/?fa=Articles.showArticle&art_aid=102488.

29 DEW Labs. (2010, April 17). How To: Get Into DEWlabs. Retrieved August 7, 2010 from http://dewlabs.blogspot.com/2010/04/how-to-get-into-dewlabs.html.

30 Federal Trade Commission Bureau of Consumer Protection. (2010, December 1). A Preliminary FTC Staff Report on Protecting Consumer Privacy in an Era of Rapid Change: A Proposed Framework for Businesses and Policymakers. pp. 35-38. Retrieved June 13, 2011 from www.ftc.gov/os/2010/12/101201privacyreport.pdf.

31 Fair Isaac. The Case for Customer Centricity. Retrieved August 12, 2010 from http://www.cxo.eu.com/article/The-Case-for-Customer-Centricity.

32 FICO. (2009). Boosting Sales and Site Traffic, Coca-Cola Breaks Ground in Customer Loyalty. Retrieved August 12, 2010 from http://www.fico.com/en/FIResourcesLibrary/Coke_Success_2520CS.pdf. (Note: The Precision Marketing Manager also "references a database with over 1600 third party sources to match disparate and inconsistent consumer data from multiple locations to create a single data warehouse of identifiable consumers. The result is an accurate 360 view of each customer.")

33 FICO. Precision Marketing Manager Product Sheet. Retrieved August 12, 2010 from www.fico.com/en/Products/DMApps/Pages/FICO-Precision-Marketing-Manager.aspx.

34 FICO. (2009). Boosting Sales and Site Traffic.

35 Quinton, B. (2008, February 1). Coke's Kruse Control. Promo Magazine. Retrieved August 16, 2010 from http://promomagazine.com/interactivemarketing/cokes_kruse_control_coca_cola_interactive_0201/index.html. (Note: Coca-Cola's Carol Kruse did say that despite online's measurability, "it's very hard to track the influence of any of our marketing efforts on a purchase decision." She also illustrated how Coca-Cola understood that in the online world, a brand had to be present simultaneously on multiple platforms: "Take Sprite. We have the Sprite.com Web site. We have the Sprite Yard, which is a mobile program. Sprite is part of MyCokeRewards.com. And we have a Facebook page with an app, Sprite Sips. It doesn't matter whether the experience happens on the Sprite Web site, on Facebook or on a cell phone.")

36 NeuroFocus, Inc. (2009, April 2). NeuroFocus Receives Grand Ogilvy Award from The Advertising Research Foundation. Retrieved June 20, 2011 from http://www.neurofocus.com/news/ogilvy_great_minds.htm.

37 Randall, K. (2009, September 15). Neuromarketing Hope and Hype: 5 Brands Conducting Brain Research. Fast Company. Retrieved June 20, 2011 from http://www.fastcompany.com/blog/kevin-randall/integrated-branding/neuromarketing-hope-and-hype-5-brands-conducting-brain-resear.

38 MediaPost.com. Media Magazine Presents the Creative Media Awards. Research/Consumer Insights: Cheetos - Toy Box. Retrieved September 19, 2011 from http://www.mediapost.com/events/?/showID/CreativeMediaAwards.09.NYC/type/AwardFinalist /itemID/943/CreativeMediaAwards-Finalists.html.

39 Mischievous Fun with Cheetos. The 2009 ARF David Ogilvy Awards. Retrieved September 19, 2011 from http://thearf-org-aux-assets.s3.amazonaws.com/ogilvy/cs/Ogilvy-09-CS-Cheetos.pdf.

40 Mischievous Fun with Cheetos.

41 TheARF.org. The ARF 2009 David Ogilvy Awards. Retrieved September 19, 2011 from http://www.thearf.org/assets/ogilvy-09.

42 PRNewswire.com. NeuroFocus Receives Grand Ogilvy Award from the Advertising Research Foundation. Retrieved September 19, 2011 from http://news.prnewswire.com/DisplayReleaseContent.aspx?ACCT=ind_focus.story&STORY=/www /story/04-02-2009/0005000077&EDATE=.