Reimagining public space to benefit health and foster community: A case study of Salinas’ annual Ciclovía

Thursday, March 29, 2018

It’s a warm, sunny October afternoon in Salinas, California, and along East Alisal Street, one of the city’s busiest roads, not a car is in sight. A mile-and-a-half stretch of the street has been closed off to automobiles and is bustling with another kind of activity. In one direction, children are playing in a bouncy castle; in another, dancers are performing carefully choreographed routines; and everywhere in between, people are walking, biking, talking and celebrating their community as part of Salinas’ fourth annual Ciclovía, which is Spanish for “bike path.”

With music and laughter filling the air, the event looks and feels like a giant kid- and family-friendly block party. However, a stroll down East Alisal reveals that it is much more than that. Each side of the street is flanked by dozens of booths, with local nonprofits, community groups, city staff and others engaging with local residents and offering a range of resources on everything from health care to housing discrimination. One group is busy registering new voters, while another is helping to educate people about water conservation amid the state’s ongoing drought. Yet another is reaching out to young people in an effort to improve their literacy skills.

Ciclovía Salinas’ purpose and benefits, then, have many layers.

“You’re asking people to reimagine what a space can be,” said Salinas resident Eric Mora, who ran a booth at the 2016 Ciclovía on behalf of the National Steinbeck Center. “Especially with this area — it’s a very high-traffic area. People seldom walk here. There’s a lot of cars, so it’s kind of hard. It’s nice to give people the opportunity to see what the street looks like from a different angle when they’re not rushing to get from point A to point B.” For many, that reimagining starts with health. As the name suggests, Ciclovía provides an opportunity for community members to ditch driving for a day and be active, and each booth that participates in the event is required to include some type of physical activity component at its station.

“You’re asking people to reimagine what a space can be,” said Salinas resident Eric Mora, who ran a booth at the 2016 Ciclovía on behalf of the National Steinbeck Center. “Especially with this area — it’s a very high-traffic area. People seldom walk here. There’s a lot of cars, so it’s kind of hard. It’s nice to give people the opportunity to see what the street looks like from a different angle when they’re not rushing to get from point A to point B.” For many, that reimagining starts with health. As the name suggests, Ciclovía provides an opportunity for community members to ditch driving for a day and be active, and each booth that participates in the event is required to include some type of physical activity component at its station.

At the same time, the event aims to improve community cohesion in Salinas, which has a long history of racial division and tension between the city and community, among other social challenges. Krista Hanni, the planning, evaluation and policy manager at the Monterey County Health Department, said that as Ciclovía participants bicycle and walk, “they are creating community as they go along. They’re interacting with neighbors and people from other neighborhoods that they might not have had a chance to interact with as much before — and certainly not in a parklike atmosphere and on a street. You don’t expect the street to be like a park.”

Others say they hope the event will increase safety and help Salinas discard its image as a hotspot for violence. “We have a real bad negative stigma,” said Israel Villa, a Ciclovía volunteer who also works for Motivating Individual Leadership for Public Advancement (MILPA). “There’s definitely too much violence here. However, there’s a lot of good people in this community of all colors. We care about our community. It’s not just all the stuff you see on the media.”

Others say they hope the event will increase safety and help Salinas discard its image as a hotspot for violence. “We have a real bad negative stigma,” said Israel Villa, a Ciclovía volunteer who also works for Motivating Individual Leadership for Public Advancement (MILPA). “There’s definitely too much violence here. However, there’s a lot of good people in this community of all colors. We care about our community. It’s not just all the stuff you see on the media.”

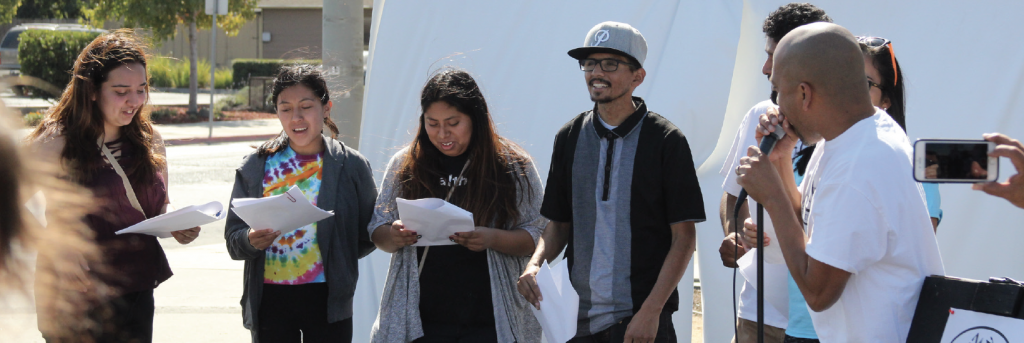

Finally, Ciclovía is helping to empower community members, especially youth, to play a central role in making these changes happen. The entire event is youth-led, with high-school students doing everything from coordinating logistics to recruiting volunteers and promoting the event widely to ensure a strong turnout.

Although addressing the root causes of racial injustice, violence and inequitable health outcomes is beyond the scope of Ciclovía — or any single event — organizers hope that it will help encourage further action. To learn how it is doing that, this case study explores the origins of Ciclovía, some of its successes and setbacks, the community’s vision for the future and lessons learned.

Why Ciclovía?

Salinas is a mid-sized city of just over 161,000 people, located fewer than 10 miles from the Monterey Bay and roughly 85 miles from the San Francisco Peninsula. Known as the birthplace of the late Nobel Laureate John Steinbeck, who based many of his works there, the city boasts a robust agricultural industry and lush vineyards. It has a mild climate, with average temperatures in the low 60s to mid-70s yearround. Set against the backdrop of the Santa Lucia and Gabilan mountains, Salinas is rich in natural beauty. It is also rich in cultural diversity, with large populations of Latinos, Asian Americans and undocumented immigrants.

But in spite of the city’s many assets, it experiences significant social and economic struggles. Generations of systemic racism, exploitation and disinvestment have fueled racial injustices and led to high rates of poverty and related issues, such as low high school graduation rates, low homeownership rates, and a median household income that falls below both the state and national average. And although the city’s violent crime rate has been declining, Salinas remains known for its history of gang rivalries, homicides and police violence — a negative narrative that has proven hard to shed.

The community, with cooperation from the city, is now working to rewrite this narrative and eliminate the unjust policies and practices that, for too long, have prevented too many Salinas neighborhoods from flourishing. Ciclovía is an outgrowth of those efforts and an extension of past social movements. The groundwork for it was laid in 2010 when The California Endowment funded the National Compadres Network (NCN) to bring to Salinas its “healing-centric” framework for change, which asserts that “communities possess the knowledge and skills they need to heal themselves from the impacts of institutional and systemic oppression, as well as transform the policies, procedures and practices that have caused such harm.” That same year, the Endowment selected East Salinas as one of the sites for its 10-year Building Healthy Communities (BHC) initiative, which was created to improve health outcomes in and “change the narrative” of 14 of California’s communities most plagued by health inequities. NCN then trained BHC staff, along with scores of other local practitioners, to apply its framework to social justice and health equity work.

The community, with cooperation from the city, is now working to rewrite this narrative and eliminate the unjust policies and practices that, for too long, have prevented too many Salinas neighborhoods from flourishing. Ciclovía is an outgrowth of those efforts and an extension of past social movements. The groundwork for it was laid in 2010 when The California Endowment funded the National Compadres Network (NCN) to bring to Salinas its “healing-centric” framework for change, which asserts that “communities possess the knowledge and skills they need to heal themselves from the impacts of institutional and systemic oppression, as well as transform the policies, procedures and practices that have caused such harm.” That same year, the Endowment selected East Salinas as one of the sites for its 10-year Building Healthy Communities (BHC) initiative, which was created to improve health outcomes in and “change the narrative” of 14 of California’s communities most plagued by health inequities. NCN then trained BHC staff, along with scores of other local practitioners, to apply its framework to social justice and health equity work.

Two years later, with that infrastructure in place, the idea for hosting a Ciclovía in Salinas bubbled up when a group of youth and staff for BHC East Salinas attended a workshop on racial equity and structural racism. There, they learned about the origins of Ciclovía in Bogota, Colombia, which began implementing the health-promoting event in 1974 and currently holds Ciclovias every Sunday and on holidays from 7 a.m. to 2 p.m. After the workshop, the group began to brainstorm ways to close racial and health gaps in their own city by creating equitable opportunities to build community and increase cohesion. Inspired by the presentation, they decided to organize their own Ciclovía, now held one Sunday each fall from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m.

“We had this huge idea of intertwining all of the areas of Salinas,” Reyna Alcalá, one of workshop’s youth participants, recalled. “We wanted to go around all of Salinas. We wanted to make sure that all of the areas of Salinas connected and there wasn’t any barrier within the city where people didn’t feel safe in one area and felt different in others. We wanted to make sure the whole city was connected.”

“We had this huge idea of intertwining all of the areas of Salinas,” Reyna Alcalá, one of workshop’s youth participants, recalled. “We wanted to go around all of Salinas. We wanted to make sure that all of the areas of Salinas connected and there wasn’t any barrier within the city where people didn’t feel safe in one area and felt different in others. We wanted to make sure the whole city was connected.”

However, Alcalá noted that the group’s original concept was too big too pull off in time for the city’s first Ciclovía, so they decided to instead focus on the areas with the greatest need where they could have the largest impact. Zeroing in on East Alisal Street allowed them to do this, both because the corridor borders low-income, resourcescarce communities and because it connects these communities to more affluent areas of Salinas. The group knew that holding Ciclovía there would create a physical and symbolic bridge to unite people from different neighborhoods.

“By focusing on this area, we could improve the Salinas community in general,” Alcalá said.

From vision to reality

With a clear vision in their heads, Alcalá, along with other BHC-involved youth, started their planning process, with a goal of launching the first Ciclovía in October 2013. They knew success would require widespread support from various city agencies and the community itself, particularly young people, so outreach was an early priority.

According to City of Salinas Transportation Manager James Serrano, the city was not a tough sell on the idea. In fact, while BHC staff and youth were in their early planning stages, the city was independently investigating ways to create a more pedestrian- and bicyclist-friendly community. To learn more, Serrano and other city staff traveled to the Bay Area to hear about the region’s efforts to transition to complete streets, and they attended a presentation by none other than Gil Peñalosa, who was instrumental in instituting Bogota’s Ciclovía.

Supporting Ciclovía Salinas seemed like a natural fit, then. “It was like an emergence of the same thinking but [in] different parts of the community,” Serrano said. “We were really in support of the project right away.”

The city now absorbs all of Ciclovía’s city-related costs, with additional support from BHC East Salinas, Salinas Valley Memorial Healthcare System, Transportation Agency of Monterey County, Monterey-Salinas Transit, First 5 of Monterey County and Pedali Alpini, Inc., among others.

The city now absorbs all of Ciclovía’s city-related costs, with additional support from BHC East Salinas, Salinas Valley Memorial Healthcare System, Transportation Agency of Monterey County, Monterey-Salinas Transit, First 5 of Monterey County and Pedali Alpini, Inc., among others.

Make no mistake, though: For all the city’s contributions (financial and otherwise), Salinas youth are the ones leading the effort — a role that seems fitting in light of how young the city is: Nearly one-third of Salinas’ population is under age 18, compared to only 13 percent of San Francisco’s population being 18 or under.

To execute each year’s Ciclovía takes several months of intensive planning. BHC interns, along with young people from each of the city’s four high schools, meet once a week and divide their work into four committees: the activities committee, which is in charge of contacting businesses, community groups and others to participate in the event; publicity, which promotes Ciclovía through a combination of media outreach, social media, phone calls and flyers; logistics, which handles the permit process in the city, builds relationships with businesses, and establishes the protocols and structures for the day of the event; and the volunteer committee. The backbone of event planning, this group helps all of the other committees and recruits dozens of additional youth and adult volunteers.

Then, on the day of the event, organizers separate the 1.5-mile path along East Alisal, between Main Street and Sanborn Road, into four color-coded sections, and the volunteers are dispatched to each area. Tasks include providing maps and directions to participants, ensuring that the street barricades are not removed, and answering questions from families along the route. The end result is the total transformation of a congested roadway into a safe, fun, healthpromoting, community-gathering space.

“It takes a lot of volunteer commitment, and we are really lucky to have so many volunteers that are willing to put their little piece into making this community a better place to be,” Alcalá said.

The youth volunteers’ efforts in particular have so impressed the city of Salinas that they were recently recognized for their hard work at a City Council meeting. The National Steinbeck Center’s Mora also emphasized youth’s special role in making Ciclovía run smoothly and described the event as “a testament” to their work.

The youth volunteers’ efforts in particular have so impressed the city of Salinas that they were recently recognized for their hard work at a City Council meeting. The National Steinbeck Center’s Mora also emphasized youth’s special role in making Ciclovía run smoothly and described the event as “a testament” to their work.

“I actually went to one of their volunteer meetings,” Mora said. “I was really impressed by the fact that it’s mostly high-school-age [students] putting on the event. … It’s huge, and the fact that they’re introduced to city government and the way that it works — they’re securing all these permits to close down the streets, to get additional help from the police department. I think it’s great for them to see that their work can have real impact.”

BHC East Salinas Youth Equity Coordinator Alejandra Silva echoed this sentiment: “I have the privilege of working one-on-one in the planning meetings with these high schoolers, and let me tell you, they are interested, passionate and determined to see a brighter Salinas in the future.”

Successes and setbacks

What started as a sparsely attended event in October 2013 has now grown to a robust and highly anticipated annual gathering. In 2016, approximately 6,500 people attended, up from 2,000 at the inaugural Ciclovía, and dozens of local organizations, businesses and city agencies participated, including the Monterey Bay Central Labor Council, Central Coast Citizen Project, Project Sentinel (a nonprofit fair housing agency) and many more. Additionally, the number of youth who help plan the event has increased significantly: Just 13 young interns organized the first Ciclovía; now, between 50 and 80 interns are involved in the planning process each year.

The strong participation and turnout belie one of the event’s main successes: its ability to forge and strengthen relationships. At the 2016 Ciclovía, those relationships were evident throughout the day in the conversations and interactions taking place along East Alisal. For example, in spite of — or, perhaps because of — tension between law enforcement and residents, Salinas police officers mingled with community members, chatting with young children and posing for photos with them.

The strong participation and turnout belie one of the event’s main successes: its ability to forge and strengthen relationships. At the 2016 Ciclovía, those relationships were evident throughout the day in the conversations and interactions taking place along East Alisal. For example, in spite of — or, perhaps because of — tension between law enforcement and residents, Salinas police officers mingled with community members, chatting with young children and posing for photos with them.

“This is Salinas community at its best,” said Sgt. Angel Gonzalez, one of the police officers getting his picture taken. “As you can see, everybody’s having a great time. Everybody’s getting involved in all the different booths. People are talking; people are enjoying each other’s company. … I think every city should have a community day like this.”

Gonzalez, who is also the executive director of the Salinas Police Activities League, a nonprofit that helps to get kids involved in sports and social events, added that the best way for police to get involved in the community is through kids. “We as a police department want to be part of this community, and [Ciclovía] is a great way to do it,” he said.

Relationship-building also happens in the months leading up to the event, as youth from different parts of Salinas coming together to plan Ciclovía. “I do get to meet a lot of people and we do develop really good relationships, so in the [planning] meetings, you’re not alone,” said Monica Botello, a volunteer for the 2016 Ciclovía who attends Salinas High. “I came into this not knowing a lot of people. Now, I can walk up to anyone and say, ‘hey.'” Botello also noted that Ciclovía has boosted her confidence: “It helps me get a little bit out of my comfort zone,” she said, “I got to talk to businesses, which, normally, I don’t do that.”

Relationship-building also happens in the months leading up to the event, as youth from different parts of Salinas coming together to plan Ciclovía. “I do get to meet a lot of people and we do develop really good relationships, so in the [planning] meetings, you’re not alone,” said Monica Botello, a volunteer for the 2016 Ciclovía who attends Salinas High. “I came into this not knowing a lot of people. Now, I can walk up to anyone and say, ‘hey.'” Botello also noted that Ciclovía has boosted her confidence: “It helps me get a little bit out of my comfort zone,” she said, “I got to talk to businesses, which, normally, I don’t do that.”

Additionally, according to the health department’s Krista Hanni, the community has begun to see some positive health outcomes in the last few years, such as a reduction in violent crime rates, specifically for youth-involved victims.

In spite of these signs of progress, Ciclovía organizers have experienced pushback, namely from local business owners concerned about losing sales. To be as equitable and inclusive as possible, Ciclovía is held on Sunday, a day off for many farm-working families who form the backbone of the area’s economy. However, this is also one of local businesses’ busiest, most lucrative days, leading some shop owners along East Alisal Street to oppose the closing of the road to cars. Even so, concerns about dips in sales have decreased over time, and some businesses have begun participating in the event by setting up booths and using them to draw foot traffic into their stores.

For example, Luis Navarro, who helps out at his parents’ business, Navarro’s Furniture, said that while the store does experience lower sales on the day of Ciclovía, they use the event as a marketing tool. Last year, they did so by handing out free water and business cards and displaying dressers outside their store.

“[Customers] get familiar and then later they come in,” Navarro said. “It’s actually helped us out to get more customers in.”

Vision for the future: Next steps for a more united and vibrant Salinas

The immediate goal of Ciclovía’s organizers is to ensure that the event continues and grows into the future. Ideas include increasing the number of groups involved and potentially expanding the route beyond East Alisal Street. However, the East Salinas Building Healthy Communities initiative that gave rise to the first Ciclovía sunsets in 2020, so sustaining the event after BHC’s formal involvement ends will depend on continued interest and commitment from the city and community — especially youth.

“We see Ciclovía as a stepping stone towards further youth civic engagement and, ultimately, power in Salinas,” BHC’s Silva said. “Given that the majority of Salinas consists of people under the age of 24, for youth to claim their power and have a voice in city decisions that impact them, only makes logical sense.”

Silva went on to describe Salinas youth as “assets” and “changemakers.” “Despite their obstacles, the youth that get involved with Ciclovía are able to see the bigger picture and how Ciclovía is just the beginning to a greater movement for change in their hometown,” she said, adding, “Because Ciclovía has become better supported by the city and community, we hope more youth and residents take ownership of their streets and begin to recognize and use their collective power to push for what they need in order to thrive.”

Silva went on to describe Salinas youth as “assets” and “changemakers.” “Despite their obstacles, the youth that get involved with Ciclovía are able to see the bigger picture and how Ciclovía is just the beginning to a greater movement for change in their hometown,” she said, adding, “Because Ciclovía has become better supported by the city and community, we hope more youth and residents take ownership of their streets and begin to recognize and use their collective power to push for what they need in order to thrive.”

While Silva and others at BHC see Ciclovía as a catalyst for many types of social change, including building youth leadership, reducing racial, economic and health inequities, strengthening community ties, and transforming the narrative about Salinas, they aren’t the only ones leveraging the event with larger goals in mind. The City of Salinas has used Ciclovía as one way to engage the community in several other mutually reinforcing, place-based efforts to revitalize East Salinas. For example, the city plans to invest in complete streets — also known as a “road diet” — by building better sidewalks and protected bikeways to serve people of all ages and abilities, while minimizing loss of parking. The city has an outreach plan in place to get community input, some of which is happening through Ciclovía. The 2016 Ciclovía even included a pop-up protected bike lane — about a thousand feet of a two-way protected lane, mocked up with yellow and white road tape — to help community members visualize one of many possibilities.

Additionally, the city is involving community members in the development of an “Alisal Vibrancy Plan,” which aims to address issues such as poverty, crime, unemployment and eroding infrastructure. City documents describe the plan as an effort to “revitalize and enhance the economic, social and cultural fabric of the City’s Alisal/East Salinas neighborhoods with the goal of creating a vibrant, mixed-use, cultural district.” Documents further characterize the plan as “community-driven,” “highly participatory” and a “foundation for ongoing collaboration and partnership between the city and community.”

Partners for the Vibrancy Plan include BHC, the Local Government Commission, City of Salinas Public Works, and City of Salinas Community Development Department. The plan has also attracted youth leaders. “Some of the youth are stepping up and applying to be part of the steering committee,” Silva said. “This in itself demonstrates their commitment and hope for their hometown, Salinas.”

Lessons learned

The tremendous momentum and early successes of Ciclovía hold many lessons for other places looking to achieve similar improvements in community health and wellbeing. Here are a few:

Put community first. An event like Ciclovía would not be possible without understanding the needs of the community and making sure they will benefit from it. Similarly, the success of the Alisal Vibrancy Plan hinges on city leaders’ ability to engage with community members. “As a city, we need to listen to our constituency,” the city’s Serrano said.

Embrace different viewpoints and keep your end goal before you. The more voices at the table, the more meaningful the end result is likely to be. However, having multiple partners also increases the likelihood for delays and disagreement. With this in mind, Serrano noted that it is important to be able to work with partners who have different — and sometimes louder — voices than your own, and to not let differences of opinion derail your efforts. “You have to always remember what it’s for,” he said.

Embrace different viewpoints and keep your end goal before you. The more voices at the table, the more meaningful the end result is likely to be. However, having multiple partners also increases the likelihood for delays and disagreement. With this in mind, Serrano noted that it is important to be able to work with partners who have different — and sometimes louder — voices than your own, and to not let differences of opinion derail your efforts. “You have to always remember what it’s for,” he said.

Invest in youth leaders. Part of Ciclovía’s power lies in the fact that it’s youth-led. Instead of tacitly accepting the circumstances they were born into, young people are dreaming of what could be possible and working to make it happen. As BHC Salinas Hub Manager Andrea Manzo said, “Youth are proving to be assets in their community and dismantling the negative narrative of youth in the community. It is important for youth to be involved as the future leaders of Salinas.”

Publicize your efforts. The youth volunteers at the heart of Ciclovía conducted extensive outreach to local media and garnered significant coverage, both from print and broadcast outlets. They also amplified news of the event though social media channels, and the efforts paid off: Each year, participation in Ciclovía has grown.

Imagine a bigger picture. Similar to how Bogotá did not start Ciclovía for its own sake, but, rather, as a means to address systemic issues, Salinas sought to address and undo systemic racism and inequities through this event. Ciclovía has helped BHC East Salinas build a stronger relationship with the city and has reinforced efforts to implement a healing-informed and racial-equity focused approach to governing within the city of Salinas.

Imagine a bigger picture. Similar to how Bogotá did not start Ciclovía for its own sake, but, rather, as a means to address systemic issues, Salinas sought to address and undo systemic racism and inequities through this event. Ciclovía has helped BHC East Salinas build a stronger relationship with the city and has reinforced efforts to implement a healing-informed and racial-equity focused approach to governing within the city of Salinas.

And, finally, have patience and persistence. Planning the first Ciclovía in Salinas took over a year. And each subsequent one has taken several months of planning. “This just helps to prove that if you set your mind to it, everything’s possible,” Alcalá said. “And the community will support you and will support the youth because, after all, they are the future of our community.”

Acknowledgments

Published by: Building Healthy Communities East Salinas

Project and case study funded by: The California Endowment

Project partner: Berkeley Media Studies Group

Author: Heather Gehlert, Berkeley Media Studies Group, a project of the Public Health Institute

Copy edits: Andrea Manzo

Creative design: The Rios Company

This story, as any story, is not composed of events or policies as much as it is composed by the people involved in creating a more vibrant and beautiful community. The love they have for Salinas is the love we hope is reflected in this case study. Thank you to all of the youth who have made Ciclovía Salinas possible. Know that we have learned as much, if not more, from you as you have from the experience of being involved in this project. Your work is not in vain nor taken for granted — we have succeeded for the past five years in creating something beautiful not just for ourselves, but for everyone in this community and it is because of you.

References

1 Dieng, J.B., Valenzuela, J., and Ortiz T. (2016). Building the We: Healing- Informed Governing for Racial Equity in Salinas. Race Forward. Available at https://www.raceforward.org/system/files/pdf/reports/BuildingTheWe.pdf. Last accessed May 3, 2017.

2 Building Healthy Communities. The California Endowment. http://www.calendow.org/building-healthy-communities/. Last accessed May 3, 2017.

3 United States Census Bureau. QuickFacts. Available at http://www.census.gov/quickfacts/table/PST045215/0667000,0664224. Last accessed November 23, 2016.

4 Adami, C. (2016, Oct. 4). City Council Honors Ciclovía Volunteers. The Californian. Available at http://www.thecalifornian.com/story/ news/2016/10/04/city-council-honors-ciclov-volunteers/91580726/. Last accessed May 3, 2017.

5 Dieng, J.B., Valenzuela, J., and Ortiz T. (2016). Building the We: Healing- Informed Governing for Racial Equity in Salinas. Race Forward. Retrieved May 3, 2017 from https://www.raceforward.org/system/files/pdf/reports/BuildingTheWe.pdf.