Rejected. Reflected. Altered: Racing ACEs revisited

Wednesday, October 19, 2016It's 2016. Local and national protests rise against an ongoing stream of state-sanctioned murders. African-American lives are being lost at a frequency and in a manner that decry ethnic cleansing. Sacred Indigenous land is being desecrated for profit. African-American, Native American, Latino American, Asian American, and poor communities are facing dislocation, police violence, and a range of traumas that compose the frayed ends of America's historically racist national fabric.

It's August 2016. In the middle of an election season replete with racially charged rhetoric, immersed in Black Lives Matter actions and the rich local history of social justice movements, a group of practitioners, researchers, and community advocates come together in Richmond, California. Participants were recruited based on their affirming belief that racial oppression and white privilege contribute to trauma, adverse childhood experiences, and subsequently to health.

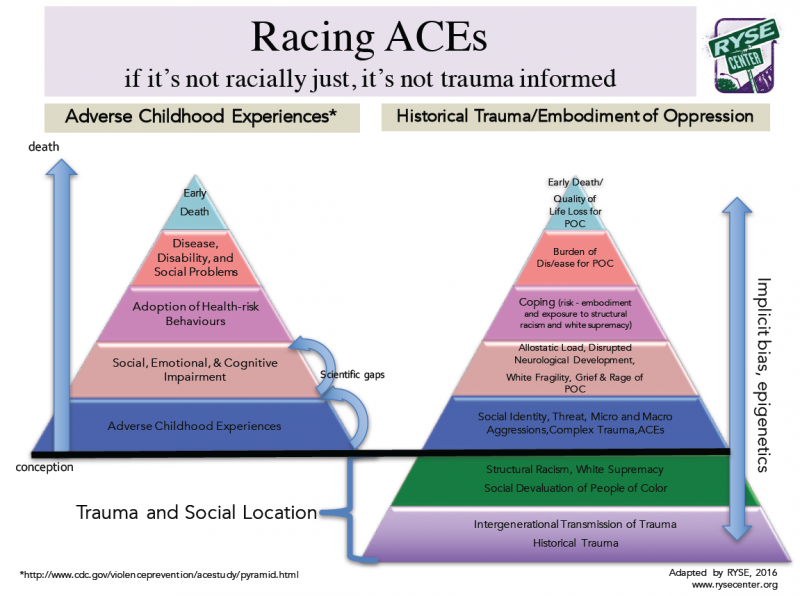

On the agenda: an exploration of how racial justice its values, investments, strategies and practices can be centered at the heart of trauma-informed work. The meeting is called "Racing ACEs," a reference to the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) study. This landmark epidemiological study caught up to and validated centuries of community-known and community-grown evidence and practice to name, understand, and heal from the physical, social, emotional, and relational impacts of childhood adversity and harm.

Though the ACEs study is a valuable tool that brings a wider audience to what clinicians, researchers, and advocates working in the field of child and adolescent trauma have said for decades, the study is also deeply problematic. Simply put, in confirming that experiences of violence, neglect, and trauma are harmful to a person's long-term health, the ACEs study fails to name racism — structural, personal, and historic — among specific root causes of modern trauma. This absence limits the study while conveying and compounding pathologies surrounding young people of color in the midst of ongoing trauma — pathologies that lead to misdiagnosis, mistreatment, and false assignments that render youth as problematic and risk-laden. When they are translated into policies, practices, and investments, these inaccurate pathologies further perpetuate and codify racial oppression and the dehumanization of young people, youth of color especially.

Who will provide a counterweight to this glaring oversight at time when racial disparities are a life-and-death equation?

In the Racing ACEs room, we are more than two-dozen carefully selected representatives engaged at the nexus of the trauma-informed and racial justice fields, forming a circle on behalf of our ancestors, our children, and ourselves.

What brings us to the room, to the work? Colonialism brought us here. Imperialism brought us here. The spine of western civilization and plunder of nations brought us here. Slavery, ethnic cleansing, all things that made this country possible, that make possible the hoarding of wealth in the hands of a few, all the ramifications of those things, of race as a structure that cages us — that is what brings us here. Oscar Grant brings us here. Mike Brown brings us here. Tamir Rice and Sandra Bland bring us here. Eric Garner. Alex Nieto. Terence Crutcher Korryn Gaines Philando Castile Alton Sterling Anthony Nuñez Jessica Williams Loreal Tsingine As kin of the murdered, we share an urgent and crucial need to speak. For them. For us.

Beyond the unacceptable travesties of inhumanity that move us forward in the names of our murdered extended-family members, we are here to heal, to move forward in a different world, one we shape daily with the momentum of our teachers, in the tradition of our ancestors who have asserted their dignity, liberty, and ideals for centuries before us. Despite the would-be indoctrination of hate that is a global force against African and Indigenous people, we are rising somewhat intact and steering our collective communities toward liberation and healing.

We first confront the fallacy of race. Since we are here alive, awake, and active, we understand race is pure fiction. We understand that although it is a fictive concept. The very notion of race (much less the implementation of sordid and hideous mechanics it makes possible) has been adopted and made concrete and serves as a basis for deadly practices targeted at people of color. We are here, then, to reveal the fantasy of race to those who suffer under it, who assume that it is real when in fact it is an idea. A boogieman. A lie.

We see it as our duty to reveal this fiction without compromise to those who carry on in its privilege, to counter and to dismantle it brick-by-brick, day-by-day, body-by-body, wresting our safety from any supremacists who guard power and work against equity. We recognize that whiteness is not a person, it's not a culture or nation, no single people can say they are its proprietors. White has proven to be a synonym for power and privilege at the cost of others' lives and with zero accountability. Whiteness is more insidious than any targetable entity. It is rather the modern base for a concrete matrix of violence, profit, and fatality. We are here to see 'whiteness' abandoned as carrier of privilege, buried as false standard, and let to rot so that all people can replenish and move forward toward a hospitable future.

Much of our time together during Racing ACEs, then, was spent in a challenging and often painful discourse. Together in that space we held and hold each other. In congregating we braided our strengths, making cable and network of them; we reinforced ourselves, refortified our ambition by showing each other our experiences. Despite our differences we put our lives on the table in front of us and recognized, reaffirmed, the core similarities of them all: a value for these same differences and an insistence that they are not a marker of worth, that our worth is our ability to be proud, dignified, and strong in the midst of a war being waged against us.

We held our pain, sharing the weight of it so that our neighbors can stand again rather than crumple beneath it. We acknowledged that our pain is sacred and so too our rage: rage at systems that perpetuate oppression; rage at systems that fail to recognize themselves as causing the trauma they claim to fight; rage at the incremental changes in cultural and organizational practice that we are forced to accept as 'good enough' when it comes to our lives and our dignity; rage that "people are dying, people are being hurt everyday, and people are being paid with our tax dollars to do it;" rage that people stripped "of family, community, safety, and other protective factors of privilege are left raw, exposed . . . hurting;" rage that so many of us came to and lived in the space "heavy with grief."

This rage, all of it, is sacred, as one of the great minds among us pointed out. And our commitment to channel it productively and heal ourselves is priority.

Also of import, we recognize the need to bring together white people and people of color to dismantle the fallacy of whiteness and address issues like white supremacy, white fragility, and the role and responsibility of white people to actively rupture and repair the harms of racial oppression. For the privileged that depend on supremacy for their own well-being and preservation, this struggle is key. How do we dismantle habits of 'whiteness" for ourselves and for diverse communities at large, especially those who profit from such habits? Given that some of us understand "white" to be another term for savage greed, how do we cross the divide to do this work? And how do we make it clear that the quest to end white supremacy is in itself a white responsibility? And that for the sake of our own health we must set that responsibility aside and leave it for the privileged to resolve, while we simultaneously fight for space in which to live safely while the privileged fail to make overdue progress.

As a room of people across a spectrum of identities, we agree that certain tasks can help prepare us all for more productive, meaningful conversations and actions toward healing racial trauma. We agree with Dr. Kenneth Hardy's analysis that conversations around racial trauma require different preparation according to different experiences. For privileged and systemically empowered 'white' participants these tasks include:

- Don't become trapped by your own good intentions;

- Avoid engaging in 'the empathy of the privileged' and framing others' experiences;

- Develop thick skin.

For people of color, the differently-abled, and marginalized, often misrepresented 'others":

- Maintain your voice and expunge toxic internalized messages;

- Overcome the "addiction" of caring for white people.

We agree that these tasks, though separate in nature are not divisive. On the contrary they serve as guide-posts for conversations about racial trauma in which pain and outrage can be expressed, heard, and better consideredall necessary elements toward disintegrating the habitual practices that plague and often thwart productive conversations regarding race and its traumatic harm.

Unless we fight together we know that more of us will be injured physically, emotionally, mentally, and culturally and while this urgency is paramount for Afro-descendants' well-being, the injury and the healing impact everyone. How do we find solidarity with one another across learned division? As African descendant, Indigenous, Asian, and Latino peoples, in a spectrum of sexual and gender identities, how can we show up for each other?

We grappled with the form that our solidarity must take so that it centers and aligns with the most structurally vulnerable among us across intersections of identity, oppression, and privilege. By naming racial trauma as our anchor, we choose a lens that assists intersectionality. Our centering on 'blackness' calls out social and political mechanisms that perpetuate "othering." In centering "blackness," we are centering on the intentionally marginalized, not just Afrodescendants, but all people whose color, ethnicity, physical and mental abilities, sexualities, gender identifications, and religious and spiritual practices fall outside the limited confines of a hetero-normative Christian white male privilege. At the same time, our centering on "blackness" allows us to focus with urgent attention on the necessary fight for Black lives in our daily struggles. In order to be intersectional, we recognize most movements are fueled and fortified by those most structurally invisible, so often queer folks of color, with whom we stand in solidarity in bolstering a necessary dynamic community identity poised toward liberation for all.

With the goal of healing and forward movement, our two days together surfaced a host of needs, questions, hopes and plans.

- Racing ACEs was, to our knowledge, the first meeting of its kind, and to many it felt long overdue. Again and again participants called for "more human, and financial resources, so we can have these conversations and do this work."

- We must foster and sustain more of these too-rare spaces — including spaces that are solely for people of color — to honor sacred pain and rage, to create joy, and to share our stories, and build power.

- Racing ACEs included a discussion of critical and practical resources for trauma informed work. If we are truly to center on liberation we need to collectively bring a racial justice lens to specific tropes and tools within that space. This includes reexamining the ACEs study in public practice, taking into account, for example, cultural and racial humility as practiced by the privileged, as well as the tremendous and all-exhausting resilience necessitated by people of color, LGBTQ people, as well as the differently-abled who must daily navigate hostile spaces in public and in private.

- We need the "will and the skill" to communicate effectively and explicitly about race and racism.

- As one participant pointed out "Until we get to a place where 'white' people recognize their harm, we can't make change." The challenge, then, is to learn what it will take to bring white people together to do white-on-white work around issues like white supremacy, white privilege and white fragility. And this particular challenge cannot and should not be the responsibility of Afrodescendants, Indigenous, Latino, Asian, or any person of color. The challenge to dismantle white privilege and harm is a challenge to be shouldered by white people whose white-onwhite work (white people working with each other) must address white fragility and combat white privilege.

- As targets in a race war, the priority to speak is ours all of ours. We must connect and build with other communities who were underrepresented in the space, including our Native, Asian/Pacific Islander, South Asian and Southwest Asian partners.

It is 2016. Today, tomorrow, and ever-forward we will continue to hold unrestricted dialogue amongst our circle, to free ourselves from white caretaking and concerns about 'white' pain, to be unabashedly and unapologetically ourselves, to move beyond the binary fiction of race, to move beyond trauma porn, beyond feel-goodisms, beyond empathy for show, beyond the circle to actual practice.

We will hold our community —our pain, our rage, and our joy — as our key to survival, as our key to honoring ancestors who are our strength, and against whom our children will measure us for generations.

We are the living frontline of resistance.

Contact:

Kanwarpal Dhaliwal, RYSE Center

Email: kanwarpal@rysecenter.org

Phone: 510-374-3401