Promotion: The 4 Ps of marketing — selling junk food to communities of color

Thursday, July 25, 2019During Black History Month in 2018, Coca-Cola ran a TV ad titled “History Moves Forward,” which juxtaposed the evolution of the iconic Coke bottle with landmark moments in Black history. The ad paid homage to the Tuskegee Airmen, Rosa Parks, and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., among others. AdAge reported that the ad aired 115 times that month, generating more than 56 million TV ad impressions across networks.1 As this example from Coca- Cola shows, unhealthy food and beverages, such as sodas, processed snacks, and fast-food meals, are often promoted in communities of color by exploiting cultural sensibilities and using images, symbolism, and language to sell products and build brand loyalty.

Such promotions raise health concerns because the foods and beverages most aggressively marketed are low in nutrients and high in sugars, salt, and fats.2 These junk foods are likely to increase disease risk or interfere with management of chronic conditions — especially in the absence of healthier food and beverage options. Meanwhile, communities of color have been the hardest hit by the current epidemic of diabetes and other nutrition-related diseases.3

Such promotions raise health concerns because the foods and beverages most aggressively marketed are low in nutrients and high in sugars, salt, and fats.2 These junk foods are likely to increase disease risk or interfere with management of chronic conditions — especially in the absence of healthier food and beverage options. Meanwhile, communities of color have been the hardest hit by the current epidemic of diabetes and other nutrition-related diseases.3

Whether it’s McDonald’s using Instagram influencers to tout a new menu item, or a more traditional Pepsi billboard, promotion is what often comes to mind when people think of marketing because it is so visible. Yet, promotion is just one way that companies engage in target marketing, the practice of using tailored approaches to sell products to specific individuals and communities, such as communities of color.

What is target marketing?

Target marketing applies the “marketing mix” principles: product, price, place, and promotion. The “4 Ps” model is foundational to today’s digital marketplace and is widely adopted by both marketing practitioners and academics. Some business experts also add other Ps, such as “personalization,” to the mix.

The targeted marketing of unhealthy food and beverages to communities of color is common across all four marketing mix categories, as companies have designed:

- products especially for communities of color;

- prices designed to appeal to specific income groups, such as “value menus” targeting low-income neighborhoods, as communities of color are disproportionately represented within them;

- places that are saturated with unhealthy food products, due to zoning in certain communities that allows concentrations of fast-food restaurants or proliferation of outdoor advertising of unhealthy food and sugary beverages4; and

- promotions that exploit cultural images, symbolism, and language that are recognizable to communities of color to sell products or build brand loyalty.

In this brief, we explain how the marketing mix principle of “promotion” works and why targeting foods and drinks high in sugars, salt, and fats to communities of color contributes to health inequities.

We speak your language

Of the “4 Ps,” promotion is likely to be the most varied and sophisticated — and exploitative. According to Key Concepts in Marketing by Jim Blythe, promotion refers to “the marketing communication used to make the offer known to potential customers and persuade them to investigate it further.” Promotion elements include “advertising, public relations, direct selling, and sales promotions.”5

In communities of color, junk foods and sugary beverages are frequently promoted in ways that perpetuate stereotypes and exploit cultural identities. Even sponsorships by junk food and beverage companies of much-needed programs, such as college scholarships for Latinx students, ultimately serve to promote a particular brand or company.

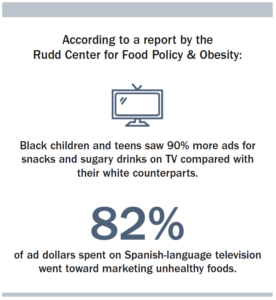

Simply put, unhealthy food and beverages are promoted more often in communities of color, especially to youth within these communities. For example, in 2017, in 2017, Black children and teens saw 90% more ads for snacks and sugary drinks on TV compared with white teens, according to a 2019 report by the Rudd Center for Food Policy & Obesity.2 Unhealthy foods represented 86% of food advertising spent on Black-targeted television programming and 82% of advertising spending on Spanish-language television, the Rudd study found.

In addition, youth of color get what researchers call a “double dose” of unhealthy food and sugary beverage marketing because they are exposed to both targeted and mainstream campaigns, particularly via digital media, which is consumed by youth of color more frequently than white youth.6

Marketers also target youth of color because they are deemed trendsetters and, therefore, exploited for what marketers call their “brand ambassador” capabilities.7 But it’s not just peer influence on youth of color that’s used to drive sales of junk food and soda. Companies exploit the popularity of celebrities of color as role models by hiring them to promote unhealthy products. These include musicians, athletes, and even historical figures.

Influencers: The new way to reach young people

The meteoric rise of social media over the past two decades fundamentally has changed the ways that brands reach consumers and has generated the practice known in the industry as “influencer marketing” — one of many promotion tactics and a new frontier of marketing. According to the digital consultancy firm Econsultancy, influencers are “individuals who have the ability to influence the opinions or buying decisions of your target audience, largely thanks to their social media following.”8

A screenshot of Instagram influencer Cierra Ramirez advertising McDonald’s Egg McMuffin in a sponsored social media post.

The influencer is a new type of celebrity who was borne out of social media. While some influencers get their start in reality television, entertainment, or other more established paths to celebrity, what differentiates influencers from their traditional celebrity counterparts — and makes them appealing to marketers — is the source of their clout: the large following they have amassed online organically. Generally, an influencer’s following is on one or more social media platforms, including YouTube, Instagram, and Snapchat, or on a blog.

With influencer marketing, companies pay influencers to promote a product, such as clothing or fast food, and the influencer then includes the product in a post online. Because of the often surreptitious placement of these products, children and teens may not realize that they are being advertised to when they see the paid (or sponsored) posts. There are now firms that represent influencers and connect them with brands or products to promote to their followers. This is a new frontier of marketing.

The food and beverage industry recognizes the power of influencer marketing to reach young audiences. For example, in 2017, McDonald’s partnered with 14 Instagram influencers to create 26 sponsored posts promoting its McCafé beverages, buttermilk crispy tenders, and fries. The Instagram influencers used branded hashtags, clearly displayed the McDonald’s logo, and tagged the official McDonald’s Instagram account in their posts. These young influencers included Latina actress Cierra Ramirez, who currently has 2.8 million followers, and Asian American YouTuber Steven Lim, who has 300,000 followers.9 The industry is so keenly aware of how effective influencer campaigns can be for reaching their target audiences that companies such as Taco Bell and Starbucks are designing menu items specifically for Instagram.10

Children and teens are particularly susceptible to influencer marketing, as these ads are coming from prominent social media figures who also frequently post non-sponsored content. The sponsored posts are interspersed throughout young people’s social media feeds with content that their friends are posting. With influencer marketing, the boundaries between what is advertising and what is not are less clearly defined than ever before. This form of advertising can make it impossible for even the savviest children to understand they are being pitched the latest products, including unhealthy foods and sugary drinks.11

The Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids recently filed a petition with the Federal Trade Commission, documenting the extensive use of influencer marketing on social media to promote cigarettes in more than 40 countries.12 Part of the basis for the complaint was that tobacco companies are training social media influencers to take “natural photos” that do not look like advertisements. Similar to the tobacco industry’s influencer marketing, the food and beverage industry’s influencer strategy purposefully blurs the lines between advertising and other content.

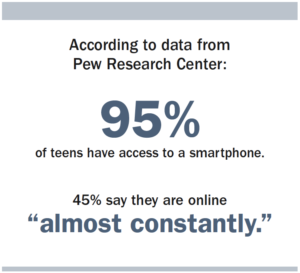

Like other forms of digital marketing that reach young people through their devices, influencer marketing is always on for children and teens. According to data from Pew Research Center, 95% of teens have access to a smartphone, and 45% say they are online “almost constantly.” Of these digitally connected teens, 85% report they use YouTube, 72% use Instagram, and 69% are active on Snapchat.13 The advertising agency RPA notes that influencers are a particularly powerful conduit for reaching Generation Z, or those born after 1995, because “Gen Z is more likely to say they trust social media and influencers when they are looking for answers than people who they actually know.”14

New advances in digital marketing, including influencer marketing, are likely to have disproportionate impacts on youth of color, as they are greater users of smartphones and other mobile technology than white youth. A survey by The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research found that Black teenagers are more likely than their white counterparts to have access to smartphones, and they are the most frequent users of Snapchat and Instagram. And Hispanic teens are more likely than white teens to report using the internet almost constantly.15 As a result of their higher use of smartphones, social media, and the internet, youth of color likely have higher exposure to influencer content, including sponsored posts about junk food and sugary drinks, than their white peers.

Influencers aren’t just being leveraged to reach young people directly — fast-food companies are also using parent-to-parent influencers to target communities of color. For example, McDonald’s targeted Latinx communities in Texas by sending personalized mailers with limited-edition games that promoted the Dollar Menu to Latinx influencers — including “mom bloggers.” This resulted in 90 social media posts from “top-tier Hispanic influencers.”16

Part of a formidable mix

Perhaps more than any of the other “Ps,” promotion is often used in combination with the other elements of the marketing mix.

A screenshot from Coca-Cola’s “Orgulloso de Ser” campaign commercial.

For example, to target Latinx consumers, Coke introduced a social media-driven commercial, “Orgulloso de Ser” (Proud to Be), as part of its popular “Share a Coke” campaign that put hundreds of different names on Coke cans. Not only did the company manufacture special Coke cans with Hispanic surnames on them, it also created temporary tattoos that it then attached to those cans. The online ad included references to Latinx gang stereotypes and featured a shot of a young Latino man putting the tattoo on his neck. The campaign kicked off Coke’s tribute to Hispanic Heritage Month.17

The campaign used promotion, along with product (specially manufactured Coke cans) and place (Coke targeted Hispanic neighborhoods in Los Angeles to film and kick off the campaign) to form an emotionally compelling marketing mix.

Additionally, promotion of another kind — employment — has been a long-standing practice at Coca-Cola and PepsiCo, specifically. Both companies hired and promoted African Americans, contracted with Black-owned companies, placed ads featuring Black people in Black-owned publications, and supported Black charitable organizations at a time in our history when many other industries actively discriminated against African Americans.18 PepsiCo and Coca-Cola remain major employers of communities of color and have robust diversity initiatives.

In addition, these and a few other junk food companies have long promoted positive images of people of color in their marketing — something that has until very recently been sorely lacking in other media.19 Supporting communities — especially those that have been historically neglected or discriminated against — is important, but it doesn’t give companies free reign to market their products that do the most harm.

What can we do?

Food and beverage companies must stop aggressively marketing their least healthy products to communities of color. We should take advantage of these long-standing relationships and acknowledge our shared responsibility to keep all communities safe and happy. We encourage continued direct dialogue among industry, community residents, and health advocates to advance solutions that will help companies improve the nutritional quality of products being marketed and sold to communities of color and low-income communities.

Advocates should create or support community-based education and advocacy campaigns that explain the practice of target marketing, as well as show how the issue is linked to civil rights concerns related to discrimination and unfairness. Companies’ inventory of tactics for targeting communities of color should be documented, publicized, and, where possible, used to engage in constructive industry discussion.

To learn more about this issue and ways to combat it, read the rest of our target marketing series, join the target marketing subcommittee of the Food Marketing Workgroup, a coalition of organizations and individuals dedicated to eliminating unhealthy food marketing to young people, especially youth of color. Those interested in joining can email workgroup co-chair and subcommittee lead Berkeley Media Studies Group at info@bmsg.org.

References

1. Dumenco S. As Black history month wraps up, watch celebrations from AT&T, Coca-Cola, CBS and Macy’s. Ad Age. https://adage.com/article/media/watch-black-history-month-ads-t-coca-cola-macy-s/312553. Published February 28, 2018. Accessed April 12, 2019.

2. Harris JL, Frazier III W, Kumanyika S, Ramirez A. Increasing disparities in unhealthy food advertising targeted to Hispanic and Black youth. UConn Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity. http://uconnruddcenter.org/files/Pdfs/TargetedMarketingReport2019.pdf. Published January 2019. Accessed April 11, 2019.

3. Committee on Accelerating Progress in Obesity Prevention; Food and Nutrition Board; Institute of Medicine. Accelerating progress in obesity prevention: Solving the weight of the nation; 2012. doi:10.17226/13275

4. Ohri-Vachaspati P, Isgor Z, Rimkus L, Powell L, Barker D, Chaloupka F. Child-directed marketing inside and on the exterior of fast food restaurants. Am J Prev Med. 2014;48(1):22-30.

5. Blythe J. Key concepts in marketing. London: Sage; 2009.

6. Grier SA. African American and Hispanic youth vulnerability to target marketing: Implications for understanding the effects of digital marketing. Paper presented at: The second NPLAN / BMSG meeting on digital media and marketing to children; June 29-30, 2009; Berkeley, CA. http://digitalads.org/documents/Grier%20NPLAN%20BMSG%20memo.pdf. Accessed April 23, 2019.

7. Boschma J, National Journal. Black consumers have ‘unprecedented impact’ in 2015. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2016/02/black-consumers-have-unprecedented-impact-in-2015/433725/. Published February 2, 2016. Accessed April 11, 2019.

8. Simpson J. What are influencers and how do you find them? Econsultancy. https://econsultancy.com/what-are-influencers-and-how-do-you-find-them/. Published June 9, 2015. Accessed January 16, 2019.

9. Case study: Fast food advertising with top Instagrammers. Mediakix. http://mediakix.com/2017/10/fast-food-advertising-instagram-influencers/. Published October 10, 2017. Accessed January 16, 2019.

10. Matousek M. Fast-food chains like Starbucks and Taco Bell are stealing a page out of Instagram influencers’ playbook. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/starbucks-and-taco-bell-mimic-instagram-influencers-2018-1. Published January 24, 2018. Accessed January 16, 2019.

11. Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, et al. Request for investigative and enforcement action to stop deceptive advertising online. Submitted to the Federal Trade Commission, August 24, 2018. https://www.tobaccofreekids.org/assets/content/press_office/2018/2018_08_ftc_petition.pdf. Accessed June 4, 2019.

12. New investigation exposes how tobacco companies market cigarettes on social media in the U.S. and around the world. Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. https://www.tobaccofreekids.org/press-releases/2018_08_27_ftc. Published August 21, 2018. Accessed February 15, 2019.

13. Teens, social media & technology 2018. Pew Research Center. http://www.pewinternet.org/2018/05/31/teens-social-media-technology-2018/. Published May 31, 2018. Accessed January 16, 2019.

14. Rubin Postaer and Associates. Identity shifters: An RPA report. https://identityshifters.rpa.com/report-download/Identity-Shifters_An-RPA-Report.pdf. Published October 2018. Accessed April 15, 2019.

15. Whack EH. AP-NORC poll: Black teens most active on social media apps. The Associated Press. https://apnews.com/7897c2f3b1954da5a15f32cb5a6632fc. Published April 20, 2017. Accessed January 16, 2019.

16. Lukovitz K. McDonald’s scores with Hispanic campaign for $1 $2 $3 menu. MediaPost. https://www.mediapost.com/publications/article/316479/mcdonalds-scores-with-hispanic-campaign-for-1-2.html. Published March 22, 2018. Accessed January 16, 2019.

17. Critics call Coke’s Hispanic Heritage month campaign ‘hispandering.’ ABC13 Houston. https://abc13.com/990371/. Published September 18, 2015. Accessed April 15, 2019.

18. Hale GE. Opinion: When Jim Crow drank coke. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/29/opinion/when-jim-crow-drank-coke.html. Published October 19, 2018. Accessed May 17, 2019.

19. Health equity and junk food marketing: Talking about targeting kids of color. Berkeley Media Studies Group. https://www.bmsg.org/resources/publications/health-equity-junk-food-marketing-talking-about-targeting-kids-color/. Published November 17, 2017. Accessed June 10, 2019.

Acknowledgments

This brief was written by Fernando Quintero and Daphne Marvel, with editing support from Lori Dorfman and Heather Gehlert. Thanks to Sarah Han and Heather Gehlert for design contributions.

This brief was funded by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

© 2019 Berkeley Media Studies Group, a program of the Public Health Institute