Preventable or inevitable: How do community violence and community safety appear in California news?

Friday, May 29, 2015Unfortunately, we’re all too familiar with violence. We see it reported daily in the news, and large numbers of us have experienced it firsthand. Yet, for all our observations of and encounters with crime and aggression, it can be challenging to understand larger patterns of violence at the community level, and harder still to understand the factors that affect when, where and how often it happens.

Community violence, defined as “intentional acts of interpersonal violence committed in public areas by individuals who are not intimately related to the victim,”1 happens when complex environmental factors like poverty, structural racism, and easy access to alcohol, drugs and weapons coincide. Like other public health problems, community violence is preventable — but it’s not often understood that way. Indeed, the public discourse around violence often reinforces the idea that it is inevitable and, as such, can only be addressed after the fact.

News coverage helps us peer into that discourse: The public gets exposed to violence (apart from personal experience) through the filter of what appears in the media. Journalists, in turn, play an important role in setting the agenda for public policy debates2-4 by deciding to report on some incidents of violence while ignoring others. If news coverage doesn’t include the community conditions that foster violence, it will be harder for policymakers and the public to make connections to policies that can prevent violence.

In fact, decades of studies of news have shown that violence coverage instills fear by highlighting the most extreme cases5 and, in journalists’ selections about what to cover, reinforces stereotypes about who commits and is affected by violence.6, 7 The patterns in news coverage can discourage positive action by buttressing assumptions that the problem is intractable and obscuring the fact that violence prevention requires a multi-sector effort. Indeed, the news usually reflects only criminal justice perspectives,7, 8 ignoring other sectors that must be involved if community violence is to be truly understood as a preventable problem.

With the support of the Northern California Kaiser Permanente Community Benefit Department, Berkeley Media Studies Group and Prevention Institute are exploring the public discourse around community violence, and community safety, in Northern California and beyond. The work will yield comprehensive tools and recommendations to help diverse stakeholders expand the frame around community violence to shift the public conversation about community violence so it is clear that violence is preventable, not inevitable, and to make room for all actors who should be part of the work of building healthy and safe communities.

A first step is understanding what the public and policymakers can learn about community violence through the news. How do stories about broad issues of community violence and safety compare to coverage of isolated incidents of crime? Who speaks in the coverage, and what do they say? How do solutions, and specifically preventive solutions, appear? In this study we answer those questions.

What we did

We collected and analyzed news stories about community violence and safety in six major newspapers covering California, with special attention to Northern California (the Contra Costa Times, The Sacramento Bee, Oakland Tribune,a Los Angeles Times, San Jose Mercury News and San Francisco Chronicle).b We chose to analyze newspapers because, although new media platforms are changing the way people consume the news, newspapers (including their online components) continue to influence local and national policy debate, and traditional news outlets remain a key source of information for the majority of news consumers.9

What we found

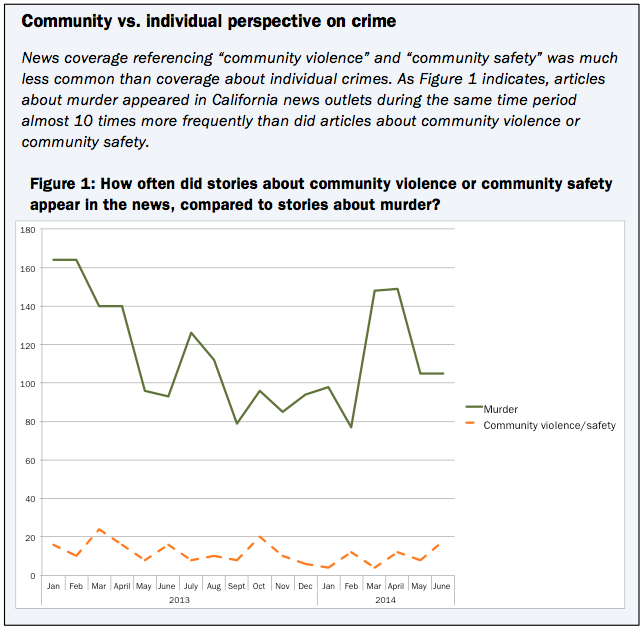

Articles about community safety rarely appear in the news, compared with stories about individual crimes.

We found a total of 296 stories from which we randomly selected half to analyze. Of the 148 articles in our sample, only 69 substantively discussed community violence. The remainder were irrelevant or included only passing mentions of community safety or community violence. Irrelevant articles tended to focus on issues like traffic safety, terrorism or local political debates in which candidates use terms like “community safety” to describe their platforms.

The majority of the coverage about community violence and community safety in California was straight news (69%); about a third was opinion writing, including op-eds, letters to the editor and editorials.

Gun violence was mentioned in almost half of relevant articles (48%), usually in connection with a murder or other fatal shooting. Other types of violence mentioned in the news included robbery and property crimes (20%), gang violence (13%), and sexual or domestic violence (9%).

Innovations or breakthroughs in policies and programs drive the news about community safety.

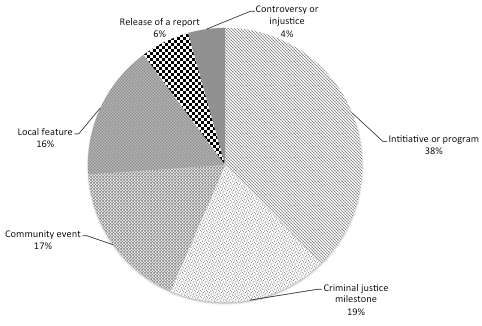

We wanted to know: When the few stories about community violence are covered in the news, why? Why that story, and why that day? Many factors can influence why reporters and editors select some stories and not others, from the details of a specific incident to what else competes for attention that day. Reporters commonly refer to the catalyst for a story as a “news hook,” so we identified the news hook for each article that addressed the question, “Why was this article published today?”

Figure 2: Why were articles about community violence and community safety in California newspapers?

Previous research on violent crime in the news has shown that milestones in the criminal justice process, like an arrest or a trial, are the news hooks for much of the coverage.10 By contrast, we found that stories that more broadly addressed community violence or community safety were most often covered because of breaking news related to a policy or safety program (38%). Examples included an article about the unveiling of a local website to connect neighborhood residents to police11 and a report on the passage of a statewide bill relating to bail reform.12 Criminal justice milestones were the impetus for 19% of articles, and events relating to community safety (such as vigils for young people killed by gun violence) were the news hook for 17% of articles. “Evergreen” feature stories — stories that were not time-bound — accounted for 16% of the articles. These included in-depth profiles of local police officers13 or other public safety figures. Other news hooks were controversies like contentious gun control court rulings (4%) or articles that highlighted the release of local crime data.

The majority of articles about community safety acknowledge that institutions play a role in solving violence.

Any debate about solutions to community violence is rooted in a fundamental question about responsibility, namely: Who is responsible for causing and for addressing community violence? Discussions about responsibility for community safety were explicit and frequent, appearing in 64% of articles.

We wanted to know, when it appears, how is responsibility characterized? Is addressing community violence depicted as a matter of individual responsibility, or does it require community and governmental action? Reporting about crime is typically “episodic” — that is, it focuses on a single event. Audiences who see episodic stories are more likely to suggest the solution lies with individuals. By contrast, “thematic” stories that place public issues in a broader context tend to elicit responses that lay responsibility for addressing that issue with institutions (like government or schools) as well.14 We found that the overwhelming majority of stories about community safety (84%) were “thematic,” and many (59%) addressed the role of various institutions or organizations in resolving violence and fostering safe communities. This is a highly unusual circumstance, as most news, including most crime and violence news, is episodic.5

State and local government were among those entities most commonly urged to address community safety through policies or initiatives. For example, California Assembly member Katcho Achadjian, in calling for more stringent reporting related to gun ownership and mental illness, concluded that “the safety of our communities relies upon government at every level doing a better job.”15 Other institutions that were called upon to act on community violence included local police departments and schools (each of these were called upon to act in 13% of articles).

To a lesser extent, California news framed violence and safety as a matter of general community or collective responsibility (25% of articles), as when Sacramento City Council member Jay Shenirer argued that “the safety of the community is in the hands of the community.”11 In community-oriented stories, we only occasionally saw language that placed the onus of responsibility for violence on survivors or their families; a rare example came from the publicity for a local safety lecture, which promised to teach participants “how to stay safe and avoid becoming a crime victim.”16

Articles about community safety overwhelmingly focus on solutions, the majority of which are criminal justice responses after the fact.

Crime coverage tends to focus on problems, rather than how to solve them.5, 17 By contrast, in another highly unusual finding, 98% of articles about community violence and safety mentioned some kind of solution, and the majority (75%) included substantive discussion of a solution.

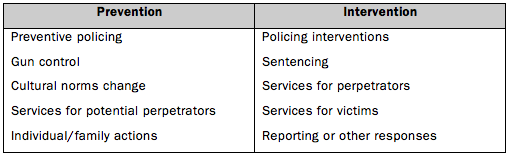

We evaluated coverage of solutions based on whether or not the focus was on individual actions or institutional or community-level approaches, and whether the approaches discussed were focused on prevention (that is, strategies to build a safe community or stop violence before it happens) or intervention (strategies to address or mitigate the impact of violence while it happens or after it occurs).

Coverage of individual incidents of crime typically includes few references to institutional or environmental approaches to addressing violence.10 In this analysis, however, we found that institutional or environmental approaches dominated the coverage of solutions in our sample (89%). The few individually focused solutions referenced included grief counseling or other services for victims of or witnesses to crimes.

Preventive strategies comprised 54% of solutions coverage, while interventions accounted for 44%. The remaining 2% of solutions coverage included vague calls for action (like “ending violence”).

Table 1: Top solutions discussed in California news coverage referencing community violence and community safety, 2013-2014

Preventing community violence

Prevention of community violence was most often framed in the context of the criminal justice system. Increasing police presence was routinely framed as an important preventive measure. The mayor of Antioch, for example, urged the city to find ways to “pay for more officers and make us safer,”18 while a Richmond resident called for “more police or more cameras or something. The streets are hot out here.”19

Non-traditional approaches to policing, like community-lead policing or partnerships, were often proposed as critical components of safe communities. An in-depth feature from the Los Angeles Times, describing a Community Safety Partnership in the Jordan Downs housing project in the Watts neighborhood of L.A., quoted one officer who said that in the past, police in that neighborhood were “the invading army. … [T]hat way doesn’t work.” He attributed to the partnership’s success to officers becoming part of the community, noting that “every good thing we do here ends up … building trust.”20

Less frequently, the coverage referenced gun control initiatives as a way to prevent community violence. A letter to the editor from the director of a local Interfaith Council, for example, called on legislators to institute background checks and ban assault weapons in order to stem gun violence.21

The news did occasionally include powerful statements that pulled back the lens to illustrate preventive solutions unrelated to criminal justice and to highlight the role of collective action and multiple sectors in building and maintaining safe communities. U.S. Representative Jackie Speier, for example, reminded San Mateo leaders in education, mental health, and law enforcement, “If we want safe schools and safe communities, we have to be willing to work together,”22 while a Richmond community organizer discussed the role of his organization in “reducing violence by building skills and employment”19 among Richmond youth. Perhaps no one was more explicit about community prevention efforts than Oakland mayoral candidate Bryan Parker, who argued that “safety is not just about more cops, but also about cleaner neighborhoods, it’s about education and about providing individuals with economic opportunities.”23

Addressing community violence after the fact

Perhaps not surprisingly, criminal justice frames overwhelmingly dominated the coverage about interventions to address community violence. Speakers routinely called for stronger police responses (20% of all solutions coverage) and harsher sentencing (10% of all solutions coverage) for those accused of violence, as when one Fremont resident declared, “It is time to enforce all laws and to be tough on crime. … We can increase the number of officers on the street to fight crime.”24 Criminal justice responses weren’t uniformly praised, however. Oakland City Council member Lynette Gibson McElhaney, for example, denounced mass incarceration and concluded, “We have been ready to throw money at solutions that don’t work because it sounds good. We cannot incarcerate our way out of the problem.”25

Root causes of violence seldom appear in the news, and preventable risk factors, like drug and alcohol access, appear even less frequently.

Discussion of the causes of violence rarely appeared in the news (26% of articles), and references to risk factors like alcohol, poverty, trauma or racism appeared even less frequently. References to race (but not racism) appeared in only five articles (7%), and references to alcohol or drug use appeared in only one article. A rare example of an attempt to address the root causes of violence came from an Oakland pastor who obliquely observed, “The people who are perpetrating violence in our communities don’t get there in a random way. They are the product of communities that have been affected in many ways.”25

Far more often, violence was attributed to failures in the criminal justice system that allowed “dangerous felons”26 to walk free. California Assembly Bill 109 (often called “realignment”), a piece of statewide legislation allowing for less violent and low risk offenders to be transferred out of state prisons, was a lightening rod for discussion in the coverage. Marc Klaas, father of Polly Klaas, who was kidnapped from her Petaluma home and murdered in 1993, argued passionately against the policy, suggesting that it would put “innocent Californians [at risk of] becoming victims of heinous crimes.”27 Sunnyvale Vice Mayor Jim Griffith denounced the bill for creating “a real smorgasbord for those who are hard-core offenders,” and concluded that cities were “literally being pillaged.”28

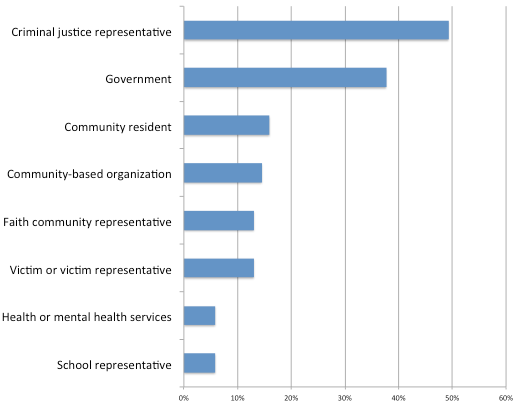

Criminal justice professionals dominate the news conversation about community safety.

The speakers quoted in the news were most often criminal justice professionals, including police officers, prosecutors and defense attorneys, and California State Attorney General Kamala Harris. All told, criminal justice professionals were quoted in 49% of articles. Representatives of state and local government were the second most frequently quoted source (38% of articles).

Figure 3: Who speaks in the news about community safety?

Community residents were quoted in fewer than one-fifth of articles. When they did appear, many provided details of their experiences with community violence or made impassioned pleas for solutions. Others provided insight into the “on the ground” workings of community safety initiatives, as when a Los Angeles youth said of a community safety partnership, “The way they are dealing with people here, treating us like human beings, it makes us see the police don’t have to be an enemy.”20

Medical providers and school representatives were largely absent from the news about community safety (appearing in only 6% of articles each). A rare article that included the perspective of an educator described the Sacramento County Office of Education superintendent’s efforts to develop school-based approaches to prevent violence by working intensively with the parents of at-risk children.29

Conclusions and next steps

News helps set the agenda and frames policy debate. Public health practitioners and prevention advocates need to make the case for the programs and policies that will make communities safe, and they need to see their perspectives reflected in news coverage so policymakers will understand what those perspectives are and why they matter. The good news from our news analysis is that unlike crime coverage, there is much greater chance of seeing prevention and solutions discussed in news of community violence and community safety. The bad news is that the solutions portrayed remain almost entirely in the realm of criminal justice. Specifically, we found that:

- Articles focusing on community violence and community safety rarely appear in the news, compared with stories about individual crimes;

- The news about community safety is driven by innovations or breakthroughs in programs or policies;

- Coverage of community safety focuses on solutions that involve institutions, most often the criminal justice system;

- Root causes and risk factors seldom appear in the news;

- Criminal justice speakers dominate the coverage, while representatives from other sectors are usually absent.

These findings hold promise for shifting the discourse around community safety to include prevention. The coverage presents many opportunities for expanding the frame and including the many different stakeholders whose participation in civic life and public policy can reshape communities. Toward that end, we propose the following media advocacy and research recommendations.

Prevention advocates and public health practitioners should:

Build on the strengths of the community safety frame to address prevention and the role of institutions.

When stories with a community safety frame do appear, they are often rich in detail about the context of violence and include institutional solutions. Expanding this frame is an opportunity to tell nuanced stories about preventing community violence — stories that underscore the role that institutions play in building and maintaining safe communities. It will be critical to develop and disseminate tools and training to equip advocates with the skills to effectively make the case for institutional solutions.

Discuss the landscape around community violence.

The news rarely addresses root causes of community violence or how to build community resilience. With tools and training, advocates can become skilled at describing the context in which community violence occurs and the specific policies and programs that need to be established, supported, and maintained to prevent it. Once people understand risk and resilience, for example, the necessity of involving multiple sectors in violence prevention will become apparent.

Expand the field of messengers to shift the discourse around community safety.

Criminal justice speakers typically advocate for criminal justice responses to violence. Expanding the field of voices to include advocates, practitioners, and public health experts will broaden the range of solutions that the public, and policymakers, will then see as viable. This broader conversation about solutions can shift the discourse from a sole focus on criminal justice to one that includes creating safe communities from the start.

One way to broaden the field of messengers is to help advocates establish new, and build on existing, relationships with journalists covering community violence. These relationships will help broaden the range of voices that speak in the news about community safety, since prevention advocates will be more likely to be called upon as sources in future articles about violence and safety initiatives in the community. Moreover, advocates will be better poised to pitch ideas that will raise the profile of violence as a preventable issue in which the entire community has a stake.

Researchers should:

Continue to examine the discourse around community safety in Northern California and beyond.

An expanded news analysis that encompasses other regions of California and beyond could answer questions like: How is news coverage of community safety evolving in light of the passage of important legislation such as California’s Proposition 47, which reduced a number of non-violent offenses from felonies to misdemeanors, resulting in the release of more than 2,000 formerly incarcerated individuals from state prisons?30 What is the impact on news coverage, in California and nationally, of demonstrations in Ferguson, Missouri, New York, and Baltimore in response to the treatment of men of color by the police? Since social media played an agenda-setting role during and after these demonstrations,31 how do conversations about community violence and prevention unfold in social media spaces? What frames are illuminating the context around community violence, and how is the case being made for programs and policies that can establish community safety?

Equipped with a solid understanding of news coverage and tools for raising their voices, community prevention advocates in California and beyond can successfully shift our public conversation from violence to safety in communities everywhere.

Related research

Acknowledgments

This paper was written by Pamela Mejia, MS, MPH; Laura Nixon, MPH; and Lori Dorfman, DrPH.

This work was funded by the Northern California Kaiser Permanente Community Benefit Department. We thank the staff of the Prevention Institute, especially Annie Lyles and Rachel Davis, for their insights and feedback in the development of this study. Thanks to Heather Gehlert for copy editing.

Endnotes

a Because they share publishers, all articles that appeared in the Oakland Tribune also appeared in the Contra Costa Times.

b We searched for articles published between January of 2013 and July 1, 2014 that referenced community safety or community violence (and all variants, such as “violence in communities” and “safety of the community”). We then read a small number of stories and adapted previous coding instruments. Before coding the full sample, we used an iterative process and statistical test to ensure that coders’ agreement wasn’t occurring by chance.

References

- Community violence. (2015). The National Child Traumatic Stress Network. Available at: http://www.nctsn.org/trauma-types/community-violence. Accessed May 11, 2015.

- Dearing J.W. & Rogers E.M. (1996). Agenda-setting. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- McCombs M. & Reynolds A. (2009). How the news shapes our civic agenda. In: J. Bryant & M.B. Oliver (Eds). Media effects: Advances in theory and research. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis. p. 1-17.

- Scheufele D. & Tewksbury D. (2007). Framing, agenda setting, and priming: The evolution of three media effects models. Journal of Communication; 57(1): 9-20.

- Dorfman L. & Schiraldi V. (2001). Off balance: Youth, race and crime in the news. Available at: http://bmsg.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/bmsg_other_publication_off_balance1.pdf Accessed May 13, 2015.

- Entman R. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication; 43(4).

- Stevens J. (2001). Reporting on violence: New ideas for television, print and web. Berkeley, CA: Berkeley Media Studies Group.

- Stevens J. (1997). Reporting on violence: A handbook for journalists. Available at: https://www.bmsg.org/pcvp/INDEX.SHTML. Accessed May 28, 2014.

- Sasseen J., Olmstead K., & Mitchell A. (2013). Digital: As mobile grows rapidly, the pressures on news intensify. In The Pew Center Project for Excellence in Journalism. The state of the news media 2013: An annual report on American journalism. Available at: http://stateofthemedia.org/2013/digital-as-mobile-grows-rapidly-the-pressures-on-news-intensify/. Accessed January 13, 2014.

- Mejia P., Cheyne A., & Dorfman L. (2012). News coverage of child sexual abuse and prevention, 2007-2009. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse; 21(4): 470-487.

- Cameron K. (2014, June 26, 2014). Sacramento police tout Nextdoor social media site for fighting crime. Sacramento Bee. Available at: http://www.sacbee.com/news/local/crime/article2602387.html. Accessed May 13, 2015.

- Woods B., Lipetzsky R., Varela J., & Adachi J. (2014, February 15). California must revise its unfair system for bail. Contra Costa Times. Available at: http://www.contracostatimes.com/opinion/ci_25137107/california-must-revise-its-unfair-system-bail. Accessed May 13, 2015.

- Breton M. (2013, December 22). Rookie cop lives immigrant’s dream. Sacramento Bee. Available at: http://www.sacbee.com/news/local/news-columns-blogs/marcos-breton/article2587080.html. Accessed May 13, 2015.

- Iyengar S. (1991). Is anyone to blame? How television frames political issues. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

- Calefati J. (2013, October 30). California auditor: Names of mentally ill barred from owning guns not reported. Contra Costa Times. Available at: http://www.contracostatimes.com/news/ci_24414673/state-auditor-names-mentally-ill-barred-from-owning. Accessed May 11, 2015.

- Locke C. (2013, January 10). Midtown safety meeting will offer tips on how to avoid street crime. Sacramento Bee, B2.

- McManus J. & Dorfman L. (2000, April 1). Issue 9: Youth and violence in California newspapers. Available at: https://www.bmsg.org/publications/issue-9-youth-and-violence-in-california-newspapers/. Accessed May 13, 2015.

- Burgarino P. (2013, February 12). Level of Antioch police staffing frustrating police chief, city leaders. Contra Costa Times. Available at: http://www.contracostatimes.com/ci_22579459/level-antioch-police-staffing-frustrating-police-chief-city. Accessed May 12, 2015.

- Rogers R. & Ivie E. (2013, April 9). Richmond: Man killed in daytime shooting in front of vocational class. Contra Costa Times. Available at: http://www.contracostatimes.com/ci_22988017/richmond-one-dead-two-injured-tuesday-morning-shooting. Accessed May 8, 2015.

- Streeter K. (2014, February 16). In Jordan Downs housing project, police are forging a new relationship. Los Angeles Times. Available at: http://articles.latimes.com/2014/feb/16/local/la-me-jordan-downs-cops-20140217. Accessed May 13, 2015.

- McGarvey W. (2013, April 26). Letter to the editor: Gun violence is a moral issue. San Jose Mercury News. Available at: http://www.mercurynews.com/ci_23118518/april-27-readers-letters-immigration-reform-gun-control. Accessed May 13, 2015.

- Cooney C. (2013, April 29). Leaders, educators, officials hold school safety summit in Redwood Shores. San Jose Mercury News. Available at: http://www.mercurynews.com/ci_23135045/leaders-officials-hold-school-safety-conference-redwood-shores. Accessed May 13, 2015.

- Williams B. (2014, June 21). Getting to know Oakland mayoral candidate Bryan Parker. Contra Costa Times. Available at: http://www.contracostatimes.com/columns/ci_25996295/byron-williams-getting-know-oakland-mayoral-candidate-bryan. Accessed May 13, 2015.

- Johnson G. (2013, June 24). Need to change way of thinking on public safety. Contra Costa Times. Available at: http://www.contracostatimes.com/ci_23530548/need-change-way-thinking-public-safety. Accessed May 13, 2015.

- Boitano D. (2013, May 16). Professor says fatal shootings not random, linked to violent social networks. San Jose Mercury News. Available at: http://www.mercurynews.com/top-stories/ci_23258666/professor-says-fatal-shootings-not-random-linked-violent. Accessed May 13, 2015.

- Halper E. & St. John P. (2013, August 2). Ruling puts release of inmates in California a step closer. Los Angeles Times. Available at: http://articles.latimes.com/2013/aug/02/local/la-me-ff-prisons-court-20130803. Accessed May 13, 2015.

- Klaas M. & Maldonado A. (2013, July 10). Spend more on prisons, don’t release felons. San Jose Mercury News. Available at: http://www.mercurynews.com/ci_23627454/marc-klaas-and-abel-maldonado-spend-more-prisons. Accessed May 13, 2015.

- Van Ells M. (2013, November 20). City official in Santa Clara County raise[sic] alarm about the state’s realignment program. San Jose Mercury News. Available at: http://www.mercurynews.com/campbell/ci_24566533/city-official-santa-clara-county-raise-alarm-about. Accessed May 13, 2015.

- Editorial: Schools set too many troubled kids adrift. (2013, October 5). Sacramento Bee. Available at: http://blogs.sacbee.com/capitol-alert-insider-edition/2013/10/editorial-schools-set-too-many-troubled-kids-adrift.html. Accessed May 13, 2015.

- Gutierrez M. (2015, March 6). California prisons have released 2,700 inmates under Prop 47. San Francisco Chronicle. Available at: http://www.sfgate.com/crime/article/California-prisons-have-released-2-700-inmates-6117826.php. Accessed May 13, 2015.

- Hitlin P. & Holcomb J. (2015, April 6). From Twitter to Instagram, a different #Ferguson conversation. The Pew Research Center: FactTank. Available at: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/04/06/from-twitter-to-instagram-a-different-ferguson/. Accessed May 13, 2015.

© 2015 Berkeley Media Studies Group, a project of the Public Health Institute