Politics over science: U.S. newspaper coverage of emergency contraception

Monday, April 27, 2015By Katie Woodruff, MPH, and Ingrid Daffner Krasnow, MPH

A condom breaks. A rapist strikes. A woman not using birth control has sex and wants to prevent pregnancy. In any of these cases, emergency contraception (EC) may be the answer. Based on the same hormones used in regular birth control pills, EC can be taken within 72 hours after unprotected intercourse to prevent pregnancy. By delaying ovulation and immobilizing sperm, it has the potential to prevent pregnancy in up to 89% of cases.1

Because EC works best when taken shortly after unprotected sex, it is important for a woman to be able to get it quickly when she needs it. For more than a decade, reproductive health advocates have worked to realize the promise of EC by making it available over the counter — without a prescription and without age restrictions — in every drugstore.

Advocates' efforts have been met at the Food and Drug Administration with resistance and roadblocks often driven by politics.2 (See timeline, Appendix.) In 2011, based on abundant scientific evidence that the drug was safe for all ages, the FDA was finally poised to approve over-the-counter status for EC without age restrictions, when Health and Human Services then-Secretary Kathleen Sebelius abruptly overruled the move. Sebelius cited concerns about the safety of the drug for young girls, but many observers concluded that she sought to deflect potential controversy over parental rights and teen sexuality as President Obama headed into his reelection campaign.3

Petitions and lawsuits about EC access continued until spring 2013, when U.S. District Judge Edward R. Korman issued a scathing rebuke to the FDA and mandated that EC be made available over the counter within 30 days. Three months and several dramatic twists later, on June 20, 2013, the FDA finally made one form of EC, Teva Pharmaceuticals' Plan B One-Step, available over the counter without age restrictions.

Reproductive health advocates celebrated this long-awaited move; Planned Parenthood President Cecile Richards called it "a huge breakthrough for access to birth control and a historic moment for women's health and equity," noting that the decision "will make emergency contraception available on store shelves, just like condoms, and women of all ages will be able to get it quickly in order to prevent unintended pregnancy."4

At the same time, advocates remain concerned about practical access to EC. The market exclusivity granted to Teva means that no other manufacturer will be permitted to sell its EC products over the counter until 2016, making Plan B One-Step the only EC brand available over the counter. Advocates worry that this will keep the price of the branded product high (initially around $50-$60 per dose), presenting a barrier to access for many low-income and young women. They are also aware that the over-the-counter policy is only as effective as its implementation; many pharmacies may still keep the product behind the counter or refuse to sell it to younger women, despite the FDA's action.

In response to the unprecedented new policy on emergency contraception, and in preparation for future work to improve practical access to EC in various settings, Princeton University's Office of Population Research invited Berkeley Media Studies Group to examine how the issue of EC has been covered in the news.

Why analyze news content?

Abundant evidence indicates that the news media play a powerful role in setting policy agendas and framing the way the public and policymakers think about and respond to issues.5,6,7 If reproductive health advocates are to advance policies to improve access and protect women, they must understand how the issue is being presented in public discussions. They must be able to make strong yet concise arguments for their perspective, as well as anticipate and counter arguments opposing them.

Additionally, advocates and concerned practitioners can look at news coverage as a proxy, albeit an imperfect one, of how the public may understand their issue. If the news served as the public's only source of information on emergency contraception, what would they know? And what wouldn't they know? What are the implications for advocates concerned about dissemination of accurate information?

Methods

To understand how emergency contraception has been covered in the news, BMSG used the Nexis database to search for articles in the four U.S. newspapers with the highest circulation (The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, USA Today, and Los Angeles Times), plus the Washington Post (8th highest circulation in the country, typically included in content analyses due to its role as the paper of record for federal policy), and the Associated Press and Reuters Health News wire services whose stories appear in newspapers around the country.

BMSG's research team searched for all pieces published in January through August 2013 that contained the terms "emergency contraception," "morning-after pill," or "Plan B." This original search yielded nearly 600 pieces, most of them not relevant to the subject (netting, for example, many stories mentioning Brad Pitt's "Plan B Entertainment," a movie production company). In order to eliminate irrelevant pieces and narrow the sample for analysis, we searched again for the same terms, with the requirement that they appear within 75 words of the term "birth control." This search yielded 178 unique news pieces, which formed the sample for analysis.

In an iterative process, Woodruff read and coded each of these 178 pieces for their article type, news source, main topic, and basic information on emergency contraception included in the piece, and identified the chief frames or arguments presented on the issue of access to emergency contraception, as well as those that we might expect to see included but did not see. In a second, closer reading, Woodruff coded each piece for the frames it included and made note of any omissions or points of interest.

There are some important considerations that may limit the generalizability of this analysis. First, the search design (collecting only articles that included the term "birth control" within 75 words of the original search terms) may have missed some substantive pieces that did not include that term. Second, Woodruff was the only coder on this work, so there is no measure of intercoder reliability; other readers may not replicate these results. Despite these limitations, the findings have important implications for people concerned about reproductive health issues and their representation in the news.

Findings: The news on emergency contraception

News sources

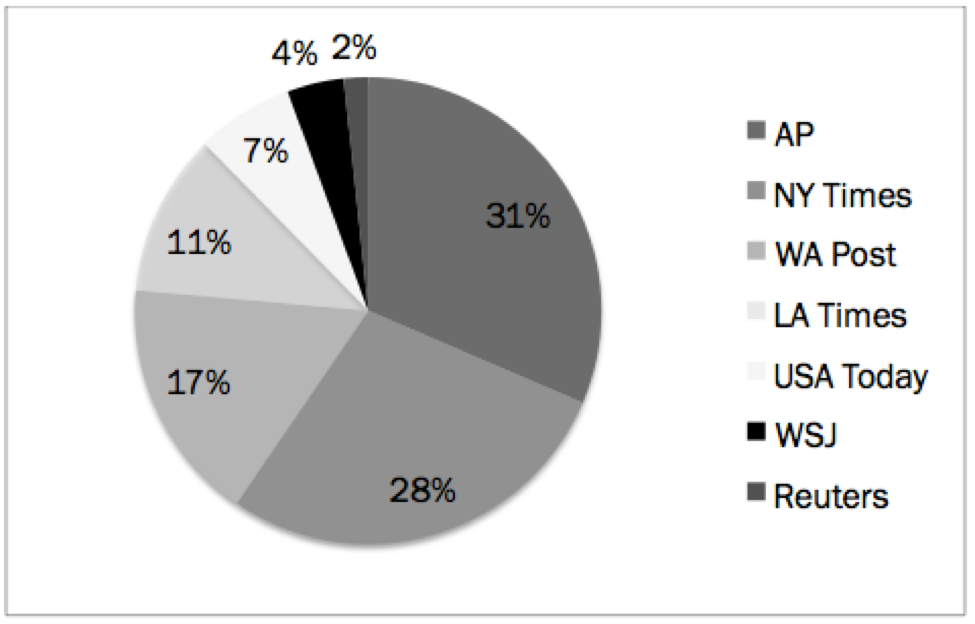

The largest single source of news on emergency contraception was The Associated Press, with 56 pieces. Next was The New York Times (50 pieces), followed by the Washington Post (30), Los Angeles Times (20), USA Today (12), The Wall Street Journal (7) and Reuters Health News Service (3). (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1: News sources in newspaper coverage of EC over the counter, January - August 2013, by percentage (n=178)

Story types

The vast majority of the sample, 72%, were news or analysis pieces; 8% were letters to the editor, and another 8% were opinion pieces or columns. Five percent were blog posts; 4% were editorials (opinion pieces by the editorial boards of the newspapers), and 2% were entertainment stories.

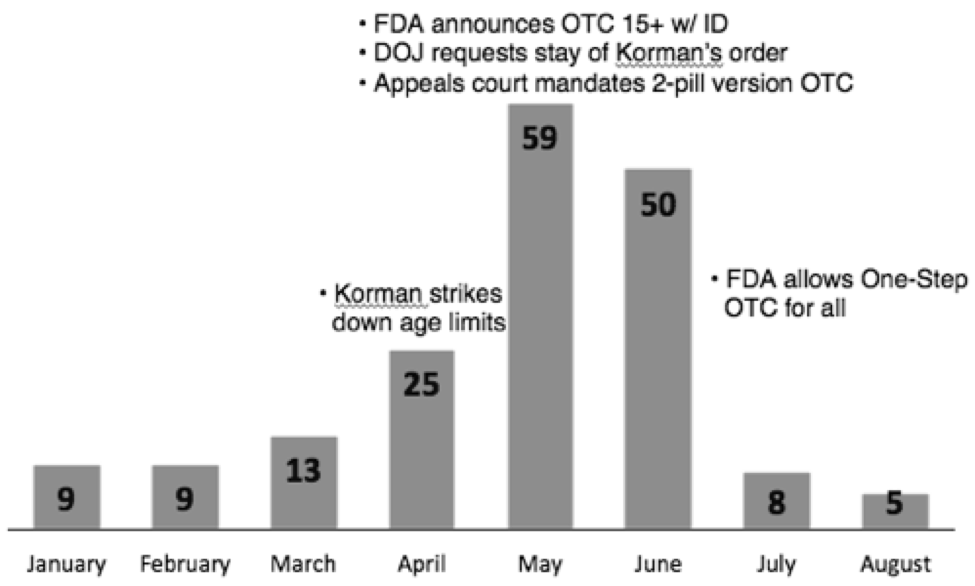

Months of publication

Three quarters of the pieces (75%) appeared in just three months of the study period, April through June 2013, when the majority of the court rulings and FDA decisions about making EC available over the counter happened. (See Figure 2.) This shows how controversial events drive news coverage; when the controversy is (apparently) resolved, news coverage drops off.

Figure 2: Distribution of national newspaper stories on EC by month, January - August 2013 (n=178)

Story topics

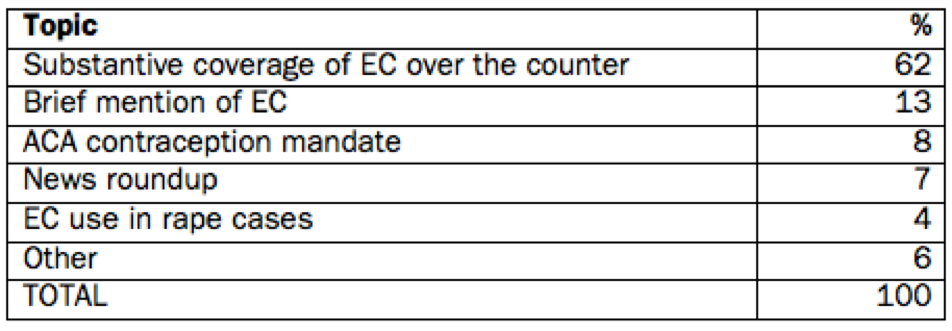

The majority of the sample (62%) comprised substantive coverage of making EC available over the counter. (See Table 1.) These included stories on Judge Korman's ruling requiring EC to be available over the counter with no age restriction (April), the FDA's announcement that it would make EC available to 15-17-year-olds with ID (late April), a U.S. Appeals Court ruling ordering the two-pill version of EC be made available without age restriction immediately (May), the Justice Department's request of a stay of Judge Korman's April order (May), and, finally, the FDA's announcement allowing over-the-counter access of Plan B One-Step to all ages (June). This category also includes stories on the general issue of making EC more available, pieces on the Oklahoma state law requiring ID for EC purchase, and business stories on Teva, the manufacturer of Plan B One-Step.

Twenty-four stories (13%) mentioned EC briefly in pieces where the overall topic of the story was not contraception at all. These included stories on the papal transition in the Catholic Church; entertainment pieces (e.g., movie reviews where a character uses EC); and stories on the politics of compromise in Washington, where the issue of EC served as one example of President Obama seeking common ground with conservatives.

Additional story topics included the Affordable Care Act's mandate for contraception coverage (8%), where EC was mentioned as a form of contraception some employers object to funding; news roundups (7%), where EC might be mentioned as one of 10 stories in a brief column recounting news highlights of the day; and the use of EC in rape cases (4%), where rape treatment policies being set in Germany and at the United Nations generated a few stories. The "other" category (6%) included topics that accounted for no more than one or two stories apiece, such as a release of a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study on contraceptive use generally; a program distributing EC in high schools; and the possibility for traditional birth control pills to be sold over the counter.

Table 1: Story topics in national news coverage of EC, January - August 2013

(n=178)

"Consumer education" on emergency contraception

Many advocates for emergency contraception have long been frustrated by news coverage of the issue, as they perceived that journalists have perpetuated misinformation, such as equating EC with the "abortion pill" or understating the timeframe during which it is effective after unprotected intercourse. To explore these issues, this study examined a range of facts and myths on EC to see how often they appeared in the coverage.

Several of the stories had a comprehensive, largely accurate "boilerplate" description of EC that showed up repeatedly in the coverage, suggesting that advocates had made a concerted effort to circulate consistent language to reporters nationwide. For example, this paragraph appeared verbatim in 10 Associated Press stories in the sample:

"The morning-after pill contains a higher dose of the hormone in regular birth control pills. Taking it within 72 hours of rape, condom failure or just forgetting regular contraception can cut the chances of pregnancy by up to 89 percent, but it works best within the first 24 hours. If a girl or woman already is pregnant, the pill, which prevents ovulation or fertilization of an egg, has no effect."

Similar paragraphs appeared in three Los Angeles Times pieces and in three Washington Post stories. With this language, reporters conveyed a baseline of accurate information about emergency contraception. However, these standard paragraphs appeared in only a minority of stories overall.

This study coded for specific facts about EC, such as the fact that it works better the sooner it is taken, that it does not cause abortion, and that it is not as effective as ongoing birth control. This study also looked for whether ella (an alternate EC product to Plan B) and the IUD were mentioned as emergency contraception methods, and whether the details of the over-the-counter EC policy were reported accurately. (See Table 2 for results.)

Table 2: Emergency contraception facts in the news

A small number of articles contained misinformation being conveyed by reporters or columnists. Three percent of the sample mentioned the "abortion pill" or RU-486 in conjunction with EC, possibly reinforcing public confusion over these two different drugs and their uses; 2% of stories contained a claim by the reporter or columnist that EC "prevents implantation" of a fertilized egg (a contention that has been scientifically discredited); and 1% of pieces claimed that EC "acts as an abortifacient" (this was a claim presented by the journalist or columnist, not by advocates quoted in the story).

In short, journalists are mostly getting the facts straight, but those facts still appear in a minority of the stories. Most coverage of EC did not include any details on how the drug works, but focused instead on the political controversy at the FDA. For example, 28% of the sample included the history of the over-the-counter EC effort at the FDA, including Secretary Sebelius' 2011 overrule of the FDA's over-the-counter EC decision. Thirteen percent of the coverage included this direct quote from Judge Korman's strongly-worded rebuke to the FDA: "[T]he secretary's [2011] action was politically motivated, scientifically unjustified, and contrary to agency precedent."8

Frames on emergency contraception: Parental queasiness vs political outrage

In the 110 pieces that focused substantively on EC over the counter (62% of the overall sample), there were various frames on each side of the debate. The literature on framing in public discourse and on analyzing frames in news coverage is deep and rich.9,10,11,12 As defined by communications scholar Robert Entman, framing is a process of select[ing] some aspects of a perceived reality and mak[ing] them more salient in a communicating text, in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation."13 In a highly contested debate, the arguments on each side of the controversy can be understood as frames by which the proponents and opponents attempt to sway public understanding of the issue.

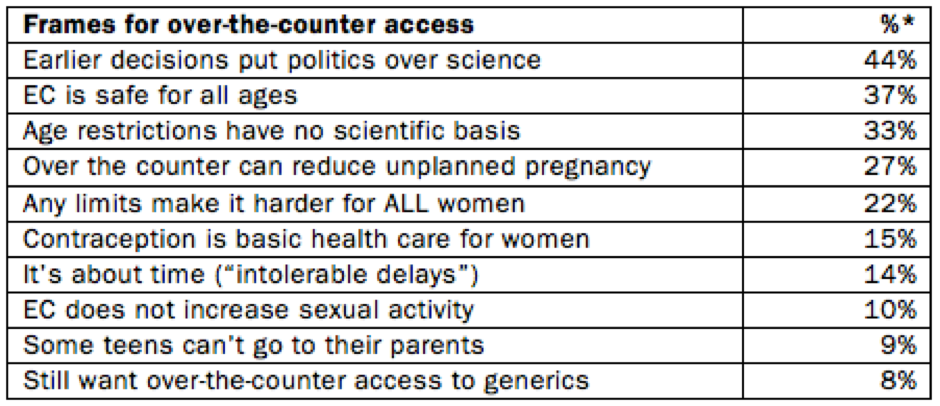

The predominant frames on each side focused on whether over-the-counter EC access is appropriate for teens. Proponents of EC over-the-counter access also framed the debate as one of politics over science.

Table 3: Frames against EC over-the-counter access in national newspapers,

January - August 2013

*Percentage of the 110 substantive over-the-counter emergency contraception stories containing this frame. More than one frame could appear in each article.

Over-the-counter access undermines parental rights

The most common argument against making emergency contraception more available was that doing so tramples on parents' rights to be involved in their children's reproductive decision-making. For example, a parent quoted in one AP article said, "If you buy Sudafed, you have to show ID. When I buy spray paint for a project for my daughter, I have to show my ID. It just baffles me that with this, which has to do with pregnancy and being sexually active, I don't have to be involved. That to me just violates my rights as a parent to have guidelines and parameters for my children."14

Another quote suggesting parental concern around EC indicated, "The slippery slope away from parental autonomy is no paranoid delusion. ... And the debate about Plan B is fundamentally about whether government or parents have ultimate authority over their children's well-being."15

Young girls should not have access to EC

Many argued that removing all age restrictions would allow very young girls to buy a drug that is "inappropriate" for them. For example, President Obama was quoted saying he was bothered by the idea of 10- or 11-year-old girls buying the drugs "as easily as bubble gum or batteries."16

Restrictions are just "common sense"

Related to the previous frame is the contention that keeping contraception out of the hands of young teens is just "common sense." The most frequent appearance of this frame was in an Obama quote from 2011, still repeated frequently in 2013 news coverage of the issue. President Obama said, "As the father of two daughters, I think it is important for us to make sure that we apply some common sense to various rules when it comes to over-the-counter medicine. ... And I think most parents would probably feel the same way."17

EC encourages sexual activity in teens

Some opponents asserted that making EC readily available "almost encourages even younger children to have unprotected sex." A quote in one article noted, "Fear of pregnancy is a deterrent to sexual activity. When you introduce something like this, it changes people's behaviors, and they have more risky sex. Teens will be counting on this morning-after pill to bail them out, and they'll have more casual encounters."18

EC endangers girls

Some advocates fear that the availability of EC exposes girls and teens to sexual coercion, subjecting them to unscrupulous men who will pressure them to have unprotected sex. They said over-the-counter access "makes young adolescent girls more available to sexual predators."19

"Substantial market confusion" will result

In several pieces, the Department of Justice, the only espouser of this frame, argued that "substantial market confusion" could result if Judge Korman's order to make EC available over the counter were enforced while appeals were pending, only to be later overturned.20

Over the counter increases potential for disease

Some opponents asserted that over-the-counter availability would increase sexually transmitted infections because it may make couples more likely to skip condoms and because no consultation with a doctor or pharmacist is required. For example, Penny Young Nance of Concerned Women for America said, "I sincerely fear for the future health and wellness of women and children, as doctors, parents, and pharmacists are eliminated from this very serious conversation about sexual activity, pregnancy, fertility, and overall health."21

EC is a "strong" or "serious" drug

Apparently conceding the strong body of research on EC's safety, opponents of over-the-counter availability didn't try to claim EC isn't safe, but still framed it as a "strong" or "serious" drug. Leveraging Kathleen Sebelius' decision to reject the FDA recommendation, one opponent of EC access stated, "Apparently the Obama administration agrees that young girls shouldn't use so serious a drug, even though proclaimed medically 'safe,' without adult supervision."22

Table 4: Frames in favor of EC over-the-counter access in national newspapers,

January - August 2013

*Percentage of the 110 substantive over-the-counter emergency contraception stories containing this frame. More than one frame could appear in each article.

Earlier decisions put politics over science

The overwhelmingly dominant frame in news coverage of the EC over-the-counter issue was that the FDA repeatedly put politics over science and, therefore, failed to do its job. For example, in a letter to the editor, one doctor wrote, "Science must be the basis for these decisions, not politics. ... This is politics trumping science again, and it's bad medicine."23 Another advocate promoting EC access stated, "This is politics at its worst and the administration should be ashamed of its duplicitous conduct."24

EC is safe for all ages

Another common frame was the idea that EC is safe — as safe as aspirin, far safer than pregnancy — and should be made available accordingly. For example, Judge Korman said in his ruling that the contraceptive "would be among the safest drugs available to children and adults on any drugstore shelf."25 In a quote that combines two frames (politics over science + EC is safe), an advocate said, "We think it's important for the agency to do what the science supports, and the science has always supported that it's safe and effective for all ages."26

Age restrictions have no scientific basis

Related to the prior two frames is the assertion that there is no evidence for age restrictions on EC availability. For example, Judge Korman blasted the government's decision to limit availability to women 17 and older as "arbitrary, capricious and unreasonable."27 Cecile Richards of Planned Parenthood made this same point when she said, "Age restrictions to emergency contraception are not supported by science, and they should be eliminated."28

Over the counter can reduce unplanned pregnancy

The fundamental hope of making EC more widely available to help reduce unplanned pregnancy rates was asserted in just over a quarter of the substantive pieces. Several pieces quoted FDA commissioner Margaret Hamburg's statement, "Research has shown that access to emergency contraceptive products has the potential to further decrease the rate of unintended pregnancies in the United States."29

Any limits make it harder for ALL women

This frame makes the case that the over-the-counter debate impacts all women who may need emergency contraception. EC is a time-sensitive drug that might be needed at any hour of day or night, but keeping it behind the counter means women of all ages sometimes have to wait until the pharmacy opens to get it. As the AP explained in its analysis, "While the case is ostensibly about rules limiting the access of teenagers to the drug, it has a practical impact on older women as well because the age restrictions mean that the contraceptives must be kept behind locked pharmacy counters and therefore aren't always available in the emergencies for which they are intended."30

Birth control is basic health care for women

This frame asserts that contraception is an essential part of overall health care for women and girls. As Judy Waxman of the National Women's Law Center put it, "There is a strong and legitimate government interest [in contraception] because it affects the health of women and babies." Referencing the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Waxman added, "Contraception was declared by the CDC to be one of the 10 greatest public health achievements of the 20th century."31

It's "about time" ("intolerable delays")

Advocates' political outrage was fueled by the long battle and frequent delays by the FDA. This statement from Judge Korman's ruling was widely quoted: "The FDA has engaged in intolerable delays in processing the petition. Indeed, it could accurately be described as an administrative agency filibuster."32

Some teens can't go to their parents

While advocates for over-the-counter access conceded that parental involvement in teens' reproductive decision-making might be ideal, the reality is that many teens don't feel they can trust their parents. One college student interviewed by the AP stated, "Not every girl has the privilege of being able to go talk to her mother in a crisis."33 An op-ed writer echoed these sentiments: "Most parents hope and pray that when their children get in a jam, they immediately turn to them for advice and love. That happens most times, but sometimes sensible behavior is overruled by teen panic."34

EC does not increase sexual activity

Some proponents asserted that making contraception available does not increase teens' sexual activity. For example, the Los Angeles Times editorialized, "The reality is that banning the morning-after pill will not deter girls from having sex. All it will do is force some of them into unwanted pregnancies."35 In another effort to debunk myths about teen sex, Dr. Angela Diaz, director of New York's Mount Sinai Adolescent Health Center said, "The fact that it's over the counter does not make people have sex. Sixty percent of young people are sexually active by 12th grade, and the more tools we have to help them be responsible, the better."36

Still want over-the-counter access to generics

A handful of pieces included the hope that cheaper generic versions would soon also be available over the counter. Judge Korman himself articulated this when he approved the FDA's decision to make Plan B One-Step available over the counter, cautioning against granting market exclusivity to Plan B maker Teva Pharmaceuticals: "Market exclusivity ... confers a near-monopoly that will only result in making a one-pill emergency contraceptive more expensive and thus less accessible to many poor women."37

Interestingly, the high price of the branded Plan B One-Step product was nearly as likely to be cited as a positive factor as a negative one. Five percent of substantive stories claimed the high price was a problematic barrier for low-income women and teens. But 4% included the perspective that the high cost was useful because it would deter teens from repeat use of EC. (Many health educators feel that anyone needing to use EC repeatedly would be better served by an ongoing method of birth control, which can be more effective than EC).

Discussion

In 2013, emergency contraception captured headlines when the FDA made Plan B One-Step available over the counter for women of any age. The substantive coverage of this major milestone in EC history (and the eight months leading up to it) was dominated by frames in favor of increasing EC access; the top five arguments in favor of EC over the counter all appeared more often than the most common argument against the over-the-counter policy. This shows that reproductive health advocates, aided by biting commentary from Judge Korman, were quite effective at getting their perspectives into the debate. As with so many public health issues, debate on EC access was framed in the news as a battle of values. In this case, the two sides boiled down to parental queasiness versus political outrage.

On the side against making EC more accessible, the predominant arguments were characterized by a morals-based perspective reflecting parental unease with teen sexuality. This was not portrayed as an extreme right-wing morality — these were not arguments that life begins at conception; nor were they arguments opposing contraception for all. Rather, these were arguments presented as "reasonable," "common sense" concerns about the implications of making EC available to young teens. The exemplar in this case was President Obama, who, in expressing his own discomfort with young girls accessing contraception, took on the role of "Father in Chief." That his comments from 2011 were still being quoted widely in the 2013 coverage reflects how much power the president has to set the agenda and how resonant this parental perspective is.

On the side in favor of making EC more accessible, arguments chiefly focused on political outrage that this safe, useful drug had not been made available already. Here the exemplar was Judge Korman, who, in colorful language that dominated the coverage, rebuked Secretary Sebelius and the FDA for the delays. In chastising the FDA and the Department of Justice for putting politics over science, he generated significant news coverage — but, ironically, the coverage itself was more about the political fisticuffs than the science.

While proponents of over-the-counter EC access were prominent in the debate, the coverage so focused on the political controversy that it failed to convey the public health facts and human reality behind the debate; it missed an opportunity to explore why increased access to contraception matters to everyday women. For example, because this policy focused on increasing access to adolescents, the news coverage left the impression that the main user base for EC is teens. Only 3% of stories in the sample noted that, in fact, women in their 20s are the primary users of emergency contraception.

Women's stories of needing emergency contraception were virtually absent from the coverage. In this sample, only one story included personal stories of women using emergency contraception. This was a piece on New York City's school-based health education program, which makes EC (along with condoms and other contraceptives) available to students at the city's high schools. In interviews with high school students conducted outside one of the schools involved, students reported having unprotected sex, not using condoms because they know they can get EC easily, and using EC repeatedly throughout the year. This kind of portrayal may reinforce the parental queasiness mentioned earlier. A wider range of women's stories would convey a more balanced picture of why women of all ages need access to EC.

Recommendations for advocates

Anyone working on a public health issue can help shape the media debate on that issue; communication needn't be left to the public relations professionals and officially designated spokespeople. Through the use of media advocacy, advocates can leverage the reach of any kind of mass media (print, broadcast, online) to advance policy debate and make their voices heard by decision-makers.

This media content analysis suggests several strategies for reproductive health advocates who want to work to make sure EC is widely accessible to women of all ages.

Decide what you want the outrage to be about.

Controversy is newsworthy — so to shape the debate, advocates must set the terms of the controversy. In the wake of the FDA action, pitch stories that put the spotlight on the areas that still need addressing. For example, following the FDA's decision to make EC available over the counter for all ages, the American Society of Emergency Contraception began to survey how EC is priced and where it is displayed in pharmacies nationwide. Results showing that some chains are still keeping it behind the counter, or that market exclusivity means the price of Plan B has increased even more, are newsworthy. Stories that put the spotlight on injustices in this area will be both controversial and productive in addressing remaining access inequities.

Cultivate and train women to tell their stories.

Reporters often use personal stories to illustrate the issues they are writing about. But on news deadlines, it can be difficult to find women, especially young women, who are at ease talking about such a sensitive issue. Advocates can help by connecting reporters with women who can tell their personal stories — what BMSG would call "authentic voices" — and can talk about how hard it was to get emergency contraception or to afford it. Help them get comfortable talking about the issue and connect them with reporters so their stories can illustrate the realities of EC.

Piggyback on breaking news.

Following the FDA's final decision, EC may be out of the spotlight, but it doesn't have to be. EC advocates should read the news with an eye toward how other coverage might relate to EC and be prepared to write letters to the editor or op-ed pieces, or to pitch a related story, in response. For example, the implementation of the Affordable Care Act and controversy over the contraception exemption lawsuits offer opportunities to reiterate the importance of making contraception affordable for all. Every time there's a story on contraception — or on sexual health, or on women's health care generally — it should include emergency contraception; if not, advocates can follow up with a letter to the editor to insert EC into the debate.

Keep educating reporters.

Clearly advocates have been doing a good job educating reporters about EC facts, as the basic facts were largely correct in this sample. Advocates should continue to reach out and follow up when stories get the facts wrong. Some reporters still need to be educated about the scientific consensus that EC does not affect implantation, and some EC opponents will continue to assert that it does; reproductive health advocates must not allow these assertions to go unchallenged. Advocates should also be sure to contact reporters to let them know when they've done stories that were fair and accurate.

Frame EC as basic health care for all women.

Rather than trigger the unease that comes when talking about sexuality among teens, advocates can stay on stronger ground by talking about contraception as basic health care that should be widely available to all women. Barriers to EC access may then be framed as unjust policies that prevent all women from accessing their rightful health care, no matter their age.

A note on working with reporters

The accuracy of reporting on the mechanism of EC in this sample shows that reporters are studying their science. This also means that advocates have been working to ensure reporters know how the drug works. As journalist turnover is high and newsrooms are getting smaller, advocates need to continue to educate reporters to ensure that stories on emergency contraception are factually correct.

What is more, advocates can build on their good work by paying attention to who is reporting on EC and what their stories say. Advocates must continue to build relationships with reporters so that they can serve as a trusted source for information when news breaks or when new research is released. Building relationships with reporters gives advocates the opportunity to educate reporters when there is a need to do so. This could include correcting an inaccurate or incomplete story or suggesting questions for reporters to ask when they are covering EC. When advocating for broader access, these questions might include, "Was cost or availability at local pharmacies an issue for women seeking timely access to EC?"

Monitoring the news will also reveal key opportunities in which advocates can "piggyback" the issue of EC availability on other, perhaps seemingly unrelated issues, such as economic security of women, child care, or job stability, all of which can be linked to a woman's ability to control her fertility.

Recommendations for reporters

Reporters have a critical role to play in clarifying the facts about the need for unrestricted access to emergency contraception. The more reporters can continue to tell compelling stories about real women who need and use EC, the clearer these facts will be to policymakers in positions to make change. Moreover, reporters can help clarify how EC works — and how it doesn't.

Ensure factually accurate information abounds about what EC is — and isn't.

Reporters can improve the public's and policymakers' understanding of EC by continuing to report that EC prevents a pregnancy from occurring after sexual intercourse. The more these facts are repeated and validated by expert scientific voices, the better policymakers will understand the stakes. Reducing (or eliminating) confusion about the mechanism of action of EC is one of the most important jobs reporters have — a job this research shows they are already doing well.

Discuss the experiences of real, everyday women who use EC.

We know that real women, in all kinds of situations, need and use EC. Some are single, perhaps in college. Some are married with children and don't want any more kids. Some were using a birth control method that failed. Some were not planning to have sex or are survivors of sexual assault. What matters most is that these varied and unique stories get told to show the wide landscape of EC use. It's also critical to show that women are seeking to control their fertility and make decisions for themselves and their families. The stories told about EC need to reflect this.

Explain the issues related to EC access (cost, current laws on age/prescription status, pharmacist compliance with age restrictions).

Just as women in various situations are seeking EC, women are also facing many unnecessary barriers to access. Though laws have changed to allow women of any age to purchase EC without a prescription, many pharmacists are uninformed or unwilling to follow the laws. Reporters can continue to explain the laws in their stories and expose those who are prohibiting legal access to EC. Reporters can also shine a light on the need for more comprehensive coverage of EC among insurers to reduce the financial burden on women to pay out of pocket for a basic medical product.

Conclusion

There is good news and bad news on emergency contraception in the news. Contrary to the fears of some advocates who still have a bitter taste over journalists confusing EC with "the abortion pill," in 2013 journalists were mostly getting the facts straight. But despite good reporting, news on the science of EC was overwhelmed by coverage of the political controversy over the FDA's actions. Frames in support of increasing access to EC dominated the debate, but the news coverage left false impressions about who uses EC. Most important, the coverage left real women's experiences out of the picture almost entirely. Advocates can keep working proactively with reporters to correct some of these omissions and advance the story on the vital role of emergency contraception in women's reproductive lives at all ages.

Appendix: A brief history of emergency contraception access in the U.S.38

May 1999: Plan B approved as a prescription drug by the FDA.

May 2004: FDA rejects application to switch Plan B from prescription to over the counter, citing lack of data on females younger than 16.

August 24, 2006: FDA approves making Plan B available over the counter to consumers 18 and older and by prescription to women aged 17 and younger.

March 23, 2009: Federal judge rules that the FDA must make Plan B available over the counter to consumers 17 and older within 30 days and urges the agency to consider removing all age restrictions.39

April 22, 2009: The FDA announces that Plan B may be sold over the counter to women and men aged 17 and older.

February 7, 2011: Teva submits actual-use study data and label-comprehension study data on females younger than 18 to the FDA in a bid to demonstrate younger women are able to understand and use the product appropriately.

December 7, 2011: The FDA is set to approve over-the-counter status for Plan B with no age restriction, based on the studies submitted by Teva. However, this action is overruled by then-Secretary of Health and Human Services Kathleen Sebelius.

March 9, 2012: Teva files an amended application to make Plan B One-Step available without prescription to consumers aged 15 and older and to allow it to be available in the family planning section of a pharmacy rather than behind the pharmacy counter; proof of age would still be required at checkout.

April 5, 2013: U.S. District Judge Edward R. Korman orders the FDA to allow over-the-counter sales of EC pills based on levonorgestrel, a synthetic progestin, with no age restriction.

April 30, 2013: The FDA approves Teva's amended application, allowing sale of Plan B One-Step on the shelf without prescription for women aged 15 and older.

May 1, 2013: U.S. Department of Justice appeals Judge Korman's April 5 ruling, seeks a stay of this order to remove age and point-of-sale requirements.

May 10, 2013: Judge Korman denies the Department of Justice's request for a stay, reprimands administration.

June 5, 2013: A three-judge appeals court denies the Department of Justice's motion for a stay, demands that two-pill generic ECPs be made available without restrictions.

June 10, 2013: The Department of Justice drops its appeal, agrees to support unrestricted approval of Plan B One-Step if generics remain age-restricted and behind the counter.

June 20, 2013: FDA approves Plan B One-Step for unrestricted sale on the shelf.

Acknowledgments

Katie Woodruff presented a preliminary version of this research at the American Society for Emergency Contraception's "EC Jamboree" in New York, NY, on Oct. 22, 2013. Thanks to the attendees who participated in the discussion during that session. Their comments and questions helped shape this paper.

Thanks to Andrew Cheyne, Pamela Mejia, and Laura Nixon of Berkeley Media Studies Group for their research support and to Heather Gehlert for copy editing. Thanks to BMSG Director Lori Dorfman for her comments and guidance on this work.

References

1 Trussell J., Raymond E., Cleland K. (2013, December). Emergency Contraception: A Last chance to prevent unintended pregnancy. Princeton University Office of Population Research. http://ec.princeton.edu/questions/ec-review.pdf. Last accessed Sept. 16, 2014.

2 Cohen G., Sullivan L., Adashi E. (2013, October). Thinking (Re)Productively — Plan B: access to emergency contraception in the legal and political cross hairs. Contraception Journal. http://www.arhp.org/Publications-and-Resources/Contraception-Journal/October-2013. Last accessed Mar. 17, 2015.

3 Harris G. (2011, December 7). Plan to Widen Availability of Morning-After Pill is Rejected. The New York Times.

4 Dennis B. and Kliff S. (2013, June 10). Obama administration drops fight to keep age restrictions on Plan B sales. The Washington Post.

5 Rogers E., Dearing, J., and Bregman, D. (1993). The anatomy of agenda-setting research. Journal of Communication, 43(2):68-84.

6 Weiss, D. (2009). Agenda-setting theory. In Encyclopedia of Communication History. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

7 Dorfman L. and Krasnow I.D. (2014). Public health and media advocacy. Annual Review of Public Health, 35:293-306.

8 Korman J. (2013, April 4). Decision in Tummino v Hamburg. https://www.nyed.uscourts.gov/sites/default/files/opinions/Tummino%20SJ%20memo.pdf. Last accessed Mar. 17, 2015.

9 Ryan, C. (1991). Prime time activism: Media strategies for grassroots organizing. Boston: South End Press.

10 Entman, R.M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication. 43 (4): 51-58.

11 Dorfman L., Wallack L., Woodruff, K. (2005, June). More than a message: Framing public health advocacy to change corporate practices. Health Education and Behavior, 32(4):320-336.

12 Major, L. (2009). Break it to me harshly: The effects of intersecting news frames in lung cancer and obesity coverage. Journal of Health Communication 14: 174-188.

13 Entman, R.M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication. 43 (4): 51-58.

14 Harpaz B. (2013, May 4). Debate over morning-after pill for 15-year olds. The Associated Press.

15 Parker K. (2013, May 5). Prude or prudent? The Washington Post.

16 Morin M. (2013, June 21). FDA clears morning-after pill for all ages. Los Angeles Times.

17 Kliff S. and Goldfarb Z. (2013, May 1). FDA move on Plan B falls short of court order. The Washington Post.

18 Rabin R.C. (2013, April 9). Contraception and the Courts. The New York Times.

19 Neergaard L. and Neumeister L. (2013, April 5). Judge making morning-after pill available to all. The Associated Press.

20 Hays T. (2013, June 2). Feds: Morning-after pill appeal officially on hold. The Associated Press.

21 Dennis B. and Kliff S. (2013, June 12). With Plan B decision, US joins other nations. The Washington Post.

22 Parker K, op cit.

23 Wilkinson T. (2013, May 5). Science first (letter to the editor). Los Angeles Times.

24 Shear M. (2013, May 11). Judge refuses to drop his order allowing morning-after pill for all ages. The New York Times.

25 Feds fight morning-after pill age ruling in NY. (2013, May 25). The Associated Press.

26 Shear M. (2013, June 12). Obama waves white flag in contraceptive battle. The New York Times.

27 AP News in Brief. (2013, April 5). The Associated Press.

28 Belluck P. and Shear M. (2013, May 2). US to appeal order lifting morning-after pill's age limit. The New York Times.

29 Morin M (2013, May 1). Morning-after pill access expanded. Los Angeles Times and others.

30 Feds fight morning-after pill age ruling in NY. (2013, May 25). The Associated Press.

31 Bronner, E. (2013, January 27). A flood of suits on the coverage of birth control. The New York Times.

32 Neergaard and Neumeister, op cit.

33 Harpaz, op cit.

34 Curtis M. (2013, May 9). Mommy and Daddy state? NC bill would require parental consent for birth control, STD treatment. The Washington Post.

35 Editorial: Obama's Plan B misstep. (2013, May 3). Los Angeles Times.

36 Neergaard and Neumeister, op cit.

37 Morin M. (2013, June 14). Ongoing debate over emergency contraception leaves little clarity. Los Angeles Times.

38 Adapted from timeline provided by Office of Population Research at Princeton University. http://ec.princeton.edu/pills/planbhistory.html. Last accessed Mar. 17, 2015.

39 Singer, N. (2009, March 23). Contraception pill strictures are eased by a judge. The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2009/03/24/health/24pill.html?_r=2&scp=2&sq=plan%20b&st=cse&. Last accessed Mar. 17, 2015.

© Berkeley Media Studies Group, a project of the Public Health Institute, 2015.