Issue 8: The debate on gun policies in U.S. and midwest newspapers

Saturday, January 01, 2000Gun violence and its prevention were thrust dramatically onto the public's agenda on April 20, 1999, with the shootings at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado. President Clinton and the Congress responded with proposals ranging from mandating background checks for gun purchases at gun shows to cracking down on juvenile offenders. Spurred by the tragedy, people across the country debated how to prevent young people from getting access to firearms.

However, the Columbine shootings did not happen in a vacuum. Communities throughout the U.S. were already grappling with issues over firearms availability and safety. In the Midwest in particular, over the next one to two years, every Midwest state except Indiana1 is expected to consider legislation that would require a concealed firearms permit to be issued to any non-convict who applies. This reflects a national strategic priority on the part of the National Rifle Association to weaken limitations on carrying concealed weapons (CCW) and fight other public health approaches to reducing handgun availability.

The national attention paid to the spring 1999 Missouri vote on carrying concealed weapons (CCW) is evidence of the media's strong interest in the controversy generated by this issue. Economist John Lott, the leading spokesperson for this perspective, is actively seeking and receiving significant coverage for his position that "the presence of concealed guns generally saves lives." In addition, other visible and vocal proponents of unfettered gun availability advance his perspective. In a letter to the editor published in The New York Times on April 14, 1999, a writer quoting Lott's research suggested that "criminals are deterred because they don't know which potential victims are armed."

However, a strong body of public health research reaches different conclusions. For example, one study found that having a gun in the home triples the risk that a resident or friend of that household will be killed with the gun.2Such research details the severe detrimental public health effects of widespread, easy access to guns.

Firearms injury prevention experts and advocates know a great deal about their issues, but they do not always have the language and strategic focus to be effective spokespeople with journalists. While they may be able to articulate the problem, many are unable to discuss solutions from a public health perspective in the concise and compelling terms journalists require. As a result, public health perspectives on the impact of handguns may be marginalized or left out of news coverage.

Why analyze media coverage?

Our objective with this analysis is to give advocates a thorough grounding in the way their issue is being portrayed in the news and thus, by extension, being presented to policy makers and the public.

Abundant evidence indicates that the news media play a powerful role in setting policy agendas and framing the way the public and policy makers think about and respond to issues.3If public health advocates are to advance the discussion of gun violence as a public health issue, they must understand how the issue is being presented in public discussions. They must be able to make strong yet concise arguments for reasonable firearm laws, as well as anticipate and counter arguments opposing such laws.

We analyzed a representative sample of newspaper coverage of policy debates around major handgun policies to determine the dominant arguments, frames, statistics and metaphors being used on both sides of the issue. For example, how prominent is the argument that citizens have the right to protect themselves with guns? How prominent are claims that gun owners also have responsibilities to the public safety and so it is reasonable to restrict where they can carry firearms?

Gun policies in newspaper coverage

To assess the range of arguments and symbols used in the debate over gun policies, we conducted a qualitative and quantitative content analysis of newspaper coverage from the spring of 1999. We searched three months of coverage, from March 1 through May 31, 1999; we deliberately chose this time frame in order to be able to sample perspectives on gun policies both immediately before and after the Columbine shootings. We searched the Chicago Tribune, Columbia Dispatch, Des Moines Register, Detroit Free-Press, Minneapolis Star-Tribune, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, Indianapolis Star, New York Times, USA Today, and the Washington Post. These papers represent one prominent newspaper from each Midwest state, in order to understand issues of specific concern to Joyce Foundation grantees in that area, as well as some national perspectives. We selected the New York Times because of its status as the "paper of record" for the country, USA Today for its broad national reach and the Washington Post for its influence in federal policy debates.

We searched these sources for all articles or opinion pieces that included in their headline or lead paragraph the terms "gun" with any form of the policy-related words: policy, control, bill, regulate, legislate, litigate, law, measure, referendum, ballot, or initiative. Our sample includes only pieces that had at least two mentions of these terms. For example, to be included, an article had to have at least two mentions of any form of the word "gun," and at least two mentions of any form of the policy-related terms, e.g., "gun" appeared twice with at least two mentions of "referendum." This eliminated casual mentions of the terms and gave us more substantive pieces on gun control issues. We also searched for articles that included the term "gun" with the phrase "John Lott," and included all of these pieces in our initial sample. All pieces were gathered from the Lexis-Nexis and Dialog electronic databases.

This process generated 515 articles, letters to the editor, op-ed pieces, columns and editorials. From this sample, we selected every third piece from each paper in order to have a manageable subsample to code. Of these (167 pieces), 24 pieces were not substantive discussions of gun issues and were eliminated from the analysis. In addition, letters to the editor that had been grouped in one record were separated into individual records for coding. The final sample totaled 170 pieces that were substantively about gun control issues. We coded each of the selected 170 pieces for whether it was news or opinion, its primary subject, who was quoted in the piece, what policies or solutions were mentioned, and what perspectives or arguments on gun policies it included.

We also coded for whether or not the piece specifically mentioned: Columbine High School or other school shootings; activity or profiles of someone from the Midwest; and John Lott or research on more guns leading to less crime.

Findings

Of the 170 pieces in our sample, 62% were news articles, 27% were letters to the editor, 8% were op-ed pieces or columns, and 3% were editorials. This breakdown includes a higher proportion of letters to the editor than we have seen in analyses of other issues, which suggests more people are writing on this topic. At the same time, letters tend to be shorter than other forms of coverage, so their frames do not dominate the coverage.

While the Columbine shootings happened in approximately the middle of our search period (April 20, 1999), in fact the salience of gun issues increased dramatically after that event. Only nine percent of the pieces appeared from March 1 through April 19, 1999; the remaining 91% appeared April 20 through May 31, 1999.

Primary subject

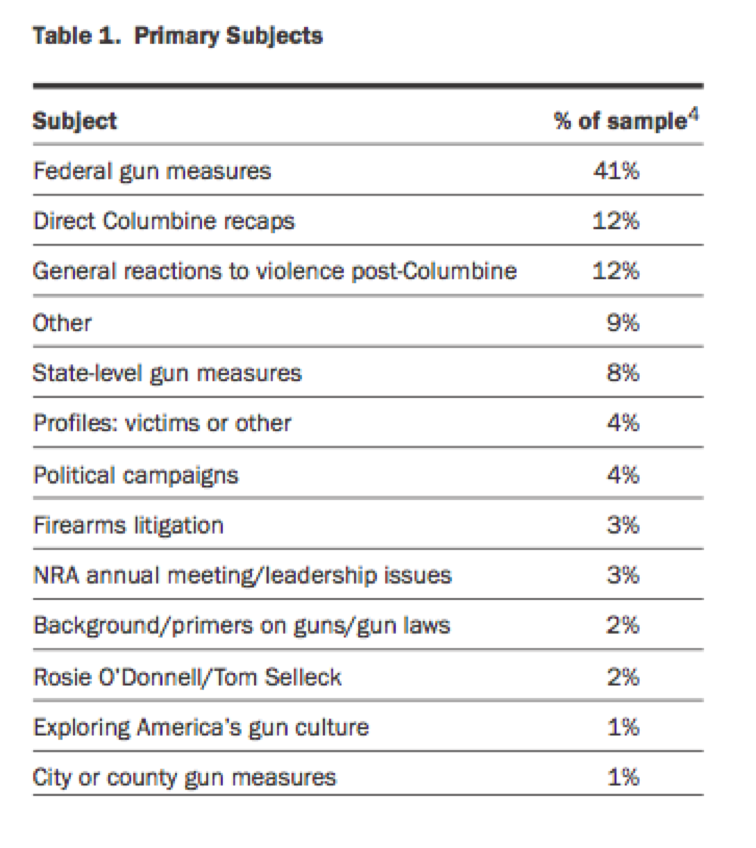

The single most common topic, comprising 41% of the sample, was federal gun policies: both President Clinton's proposals and Congressional bills to deal with gun availability and violence. (See Table 1.) Coverage of and follow-up to Columbine, both direct recaps and general reactions to violence postColumbine, made up another 24%. Other topics, including state-level gun initiatives, litigation on firearms, etc., comprised less than 10% of the sample each.

Other elements mentioned

Three-quarters of the pieces in our sample mentioned Columbine or other school shootings. Although 52% of the pieces came from Midwest newspapers, only 22% dealt specifically with activity in the Midwest; the rest dealt with national issues. John Lott or research on more guns leading to less crime were mentioned in 5% of the sample.

Who speaks?

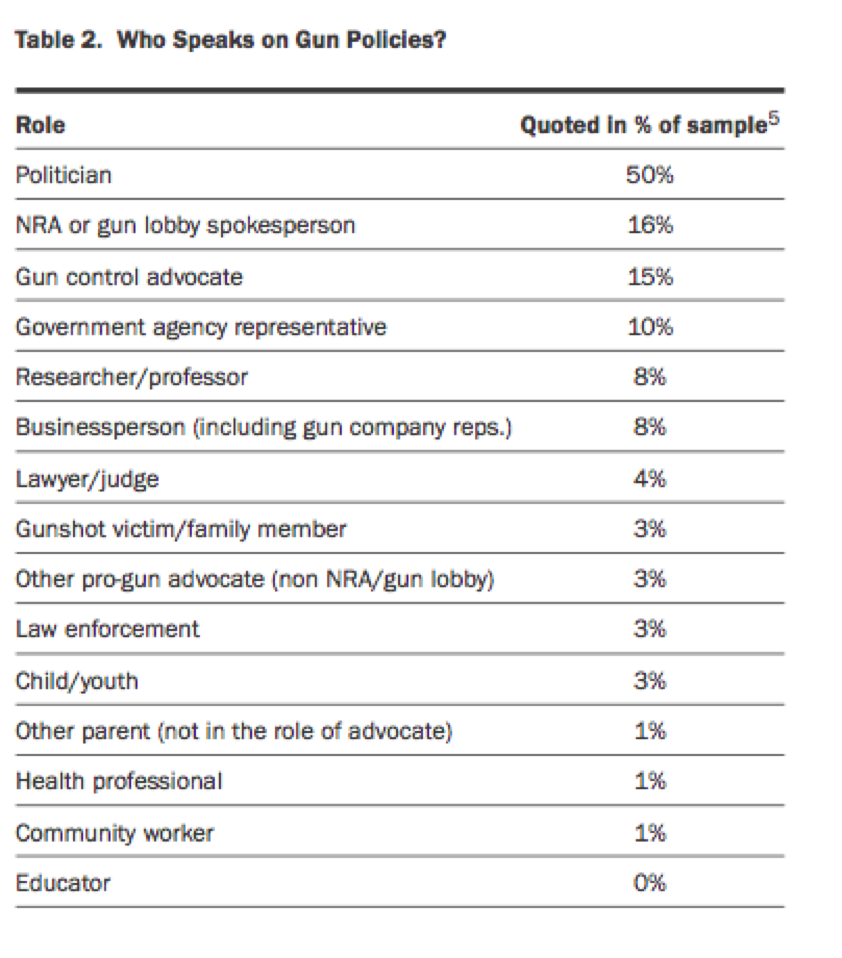

The most common speakers were politicians, who were quoted in half of the pieces. (See Table 2.) NRA or other gun lobby spokespeople and advocates for gun control policies were fairly equally represented, with each quoted in 15–16% of the sample. Gunshot victims and their families were rarely quoted, while health professionals and educators were virtually absent from the debate.

Policies mentioned

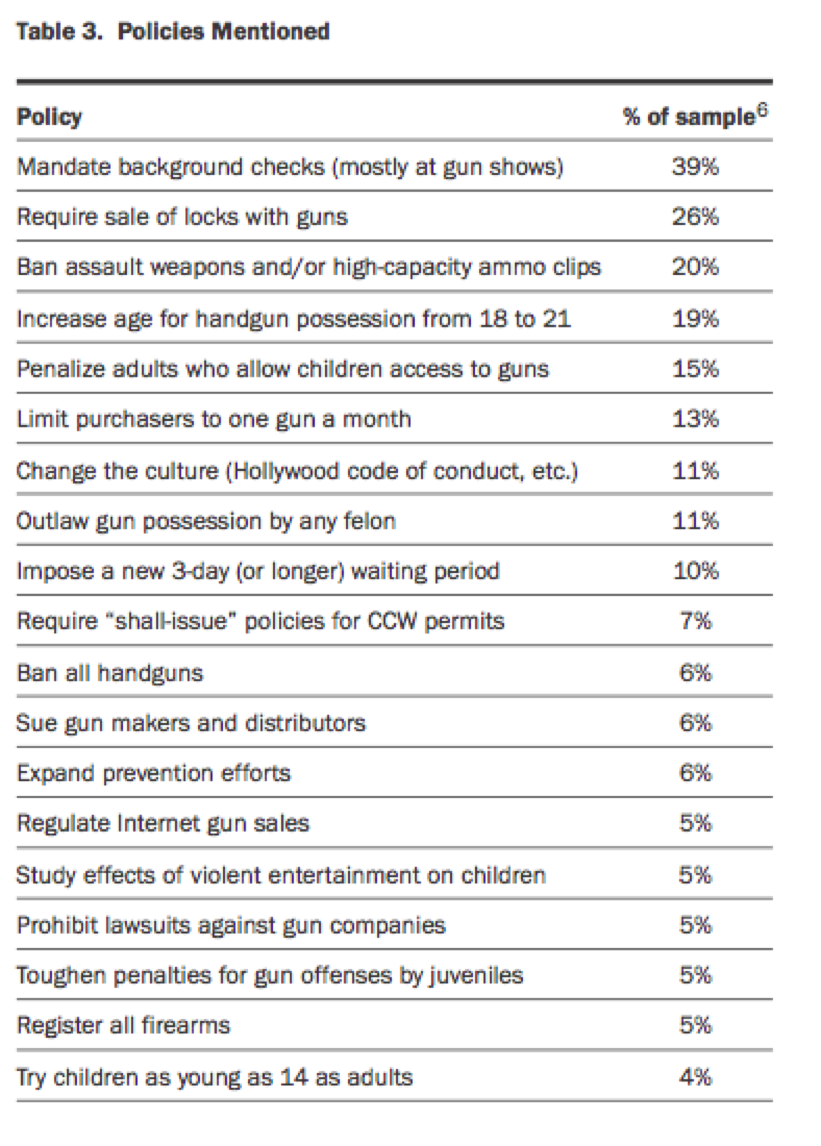

Because most of the coverage focused on Federal firearms measures, the policies described in the coverage reflect that focus. (See Table 3.) Many pieces included more than one policy or solution. The most common policy mentioned was mandatory background checks (mostly in the context of gun shows), mentioned in 39% of the sample. The mandatory sale of trigger locks or other safety devices with firearms was mentioned in 26% of the sample. All other policies were mentioned in 20% or fewer of the pieces. Not all policies reflected a public health approach, though most involved some degree of gun control.

Identifying the frames

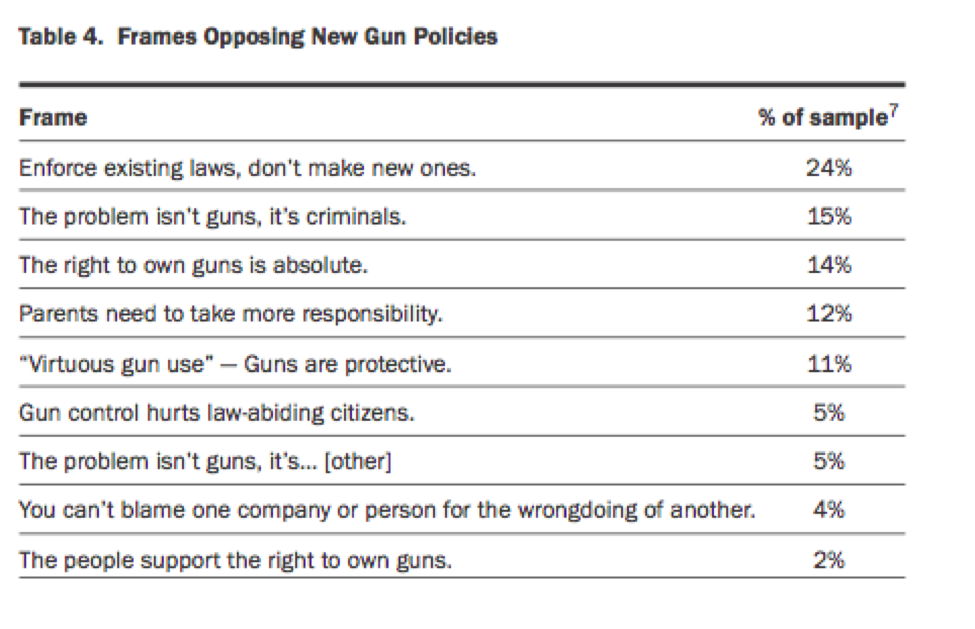

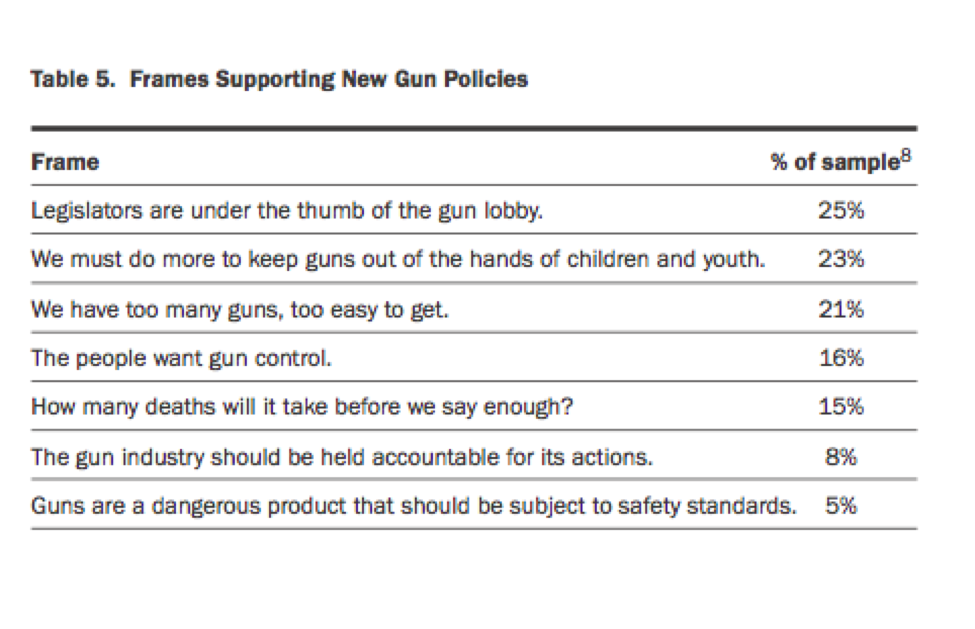

As we read the pieces on gun policies, we looked for the dominant frames on all sides of the debate. (In this case, we use the term "frame" to mean a perspective or theme that captures a common argument on an issue.) We identified 17 major frames on the issue: nine opposing new gun policies, seven in support of new gun policies (see Tables 4 and 5), and one frame that was used by advocates on both sides of the issue. Overall, the frames in support of new gun policies appeared in 62% of the sample, while frames opposing new gun policies appeared in 56% of the sample.

Frames opposing new gun policies

Enforce existing laws, don't make new ones.

The most common frame opposing new gun policies appeared in 24%9 of the sample; it posits that we should focus on enforcing existing gun laws and cracking down on criminals rather than passing new laws. This frame is most commonly voiced by Republican politicians, NRA representatives and some letter writers, who use it to accuse Clinton of grandstanding and holding double standards. They charge that "the real issue is that the Clinton administration has not done enough to enforce existing gun laws,"10 and claim, "It takes a lot of nerve to bang your fist and demand tougher gun laws while doing almost nothing to enforce the ones that already exist."11

As Wayne LaPierre said, "In Littleton, those two horrible kids, those homicidal maniacs, they broke 20 federal and state gun laws. You could have put another 50 laws on the books, and they would have broken those too."12 Patrick Buchanan makes the same point in more vivid language: "Those brutal and nihilistic and godless killers in Colorado violated 19 federal and state gun and explosives laws. To suggest passage by Congress of a 20th, 21st or 22nd law might have prevented this atrocity is delusional, and it is demagogic."13

Pro-gun forces use some compelling statistics to back up their claims that current gun laws are woefully underenforced: "6,000 students were found to have brought weapons to school in 1997 and 1998 and only 13 were prosecuted"14; "The Administration conceded that of the thousands of convicted criminals who tried to buy guns illegally over the last year and were caught by background checks, only a handful were federally prosecuted."15

The problem isn't guns, it's criminals.

The second most common frame opposing new gun policies is closely related to the first; it claims that criminal behavior, rather than the tool used, should be the primary target of change efforts. Proponents of this frame call for greater personal responsibility, rather than changes in policy. As one letter writer notes, "Criminals and disturbed persons will always find means of carrying out their intentions."16 As the NRA's Wayne LaPierre says, "In the search for those who should be held responsible, how about blaming the people who pull the trigger, set off the bombs and do the killings?"17

Proponents of this frame note that the gun is merely a tool, not the cause, of a violent act. "Millions of people use guns legally every day. Let's treat the cause, not the symptom."18 Others notes that if guns are eliminated, other tools of violence could be used: "Guns, drugs, knives, matches, scissors, clubs, rocks, etc. can all be dangerous if the intent is there. Don't you think it's about time that we quit placing the blame on tangible objects and take positive action to help our children?"19

Some proponents compare the gun to other inanimate objects which are the focus of other public health measures, and call for greater individual responsibility across the board: "Rational people realize it is the drunken drivers and not the cars, the drug abusers and not the drugs, the smokers and not the tobacco, and the shooter and not the guns."20

The right to own guns is absolute.

This frame, appearing in 14% of the sample, asserts that the Second Amendment secures the absolute right to own guns. As the NRA's Charlton Heston says, "Our mission is to remain a steady beacon of strength and support for the Second Amendment, even if it has no other friend on the planet. We cannot let tragedy lay waste to the most rare and hard-won human right in history."21

This frame also encompasses the perspective that any proposed gun-control measures constitute a slippery slope to a total gun ban. Proponents worry, for example, that limiting purchases to "one a month could lead to 'none a month.'"22 Proponents of this frame see themselves as under attack by those who would remove their right to own guns: "The only purpose of the registration law is the confiscation of all firearms in this country."23 "Any sign of weakness will beget more attacks by the anti-gun forces."24

Parents need to take more responsibility.

The next most common anti-gun control frame was seen in 12% of the sample; it claims that parents must do more to keep guns out of the wrong hands, and help children stay out of violent situations. As Orrin Hatch noted, the "'fundamental principle' is that government can't 'micromanage' parental responsibility."25 Senator Rod Grams concurred: "The answer to the horrible things that happened in Littleton are not going to be answered in the halls of Congress but in the homes of families."26

This frame is anchored in blame for the parents of the Columbine shooters — "Their parents should have known that something was wrong."27 — and expands from there to define prevention solely as the parents' job. Candidate George W. Bush asks, "The fundamental issue is, Are you and your wife paying attention to the children on a day-by-day, moment-by-moment basis?"28 A letter writer says, "To parents: The next time you fail to know where your kids are, the next time you fail to discipline your kids, the next time you fail to know what they are up to, think of the students killed in Colorado."29 Another writer suggests, "This event is a wake-up call, but not a call for more legislation or empty promises. This is a call to embrace your child. Embrace your child's friends."30

Guns are protective.

A frame appearing in 11% of the sample explores the idea of "virtuous gun use" — the concept that guns can help protect law-abiding citizens from the impulses of the criminal and insane. Responding to Michigan's "shall-issue" CCW law, a letter writer states, "This is the first time since 1927 that law-abiding people in Michigan will be able to defend their families."31 One proponent responded to claims that handguns have no legitimate purpose by claiming, "The most important legitimate use of a handgun is for self-defense away from home, when a long gun would be impractical."32 A Michigan state senator, citing Kleck's research in an op-ed, noted that "lawabiding citizens need CCW permits because more than 87% of violent crimes occur outside the home."33

John Lott's work and related research is quoted in support of this frame: "Those states with laws allowing the carrying of concealed guns have experienced drops of violent crime in the 20 percentile range."34

Lott's numbers "represent real people and show 1,570 real people died needlessly, victims of murders that would not have occurred had so-called concealed-carry laws been in effect throughout the 50 states."35 Proponents rely on this research to dismiss claims that more guns might lead to more injuries: "In the past 10 years, more than 12 states have passed concealed-weapons laws. Where are the increases in accidents, homicides and assaults?"36

In response to Columbine, some politicians and letter writers suggested that more guns on the scene might have helped, not hurt: "If there was an armed citizen at Columbine, 'perhaps someone would have ended the shooting spree before anyone other than the perpetrators got hurt.'"37 A Colorado gun lobbyist, one article reports, "said he wanted teachers to be allowed to have guns in schools, so no one would think he or she could show up and find helpless victims there."38

Other anti-gun control frames.

Other arguments opposing new gun policies appeared in less than 10% of the sample each:

- Gun control hurts law-abiding citizens (5%). "Many law-abiding gun owners come to see themselves as under siege from liberal, big-government regulators who want to complicate their lives and take away their hunting rifles."39

- The problem isn't guns, it's... [assorted other] (5%). "The problem in this country is not the prevalence of weapons. Instead, it is the scarcity of moral values."40 "So we talk of dealing with the weapon today instead of the root causes: the inhumanity, the meanness, the lack of civility."41 "We have a drug problem in Chicago, we have a breakdown in the family unit. If you solve those problems, you won't have a gun problem."42

- You can't blame one person/company for the wrongdoing of another (4%). "Suppose someone hit you on the head with a hammer. Do you sue the manufacturer of the hammer or the perpetrator?"43

- The people support the right to own guns (2%). "We don't have corporate power; we have people, and I would always rather have the power of people. By and large, when it comes down to a political showdown in which people count, the freedom to own guns wins out."44

Frames supporting new gun policies

Legislators are under the thumb of the gun lobby.

Appearing in 25% of the sample, this frame was the most common theme in the coverage we analyzed. Mostly voiced by politicians (usually Democrats) and letter writers, it is used to shame lawmakers (mostly Republicans) for being beholden to the NRA and other pro-gun interests. "If the Republican Party ever hopes to become the Smart Party, it must start by ending its thralldom to the NRA."45 Supporting this frame was controversy over the fact that Senator Craig consulted with NRA lawyers on the wording of his amendment to a key gun bill: "We cannot let the (NRA) write our gun laws,"46 said New York Congresswoman Nita Lowey.

Included in this frame are analyses of how NRA campaign contributions provide an accurate barometer of senators' votes on gun control bills: "Thirty-two of the 34 senators who supported the gun lobbying organization on each of four key votes received NRA money for their last election. Only two of the 38 senators who opposed the NRA on the same four votes received contributions from the gun group."47 As one letter writer mused, "A senator is a person of integrity. Once you buy one, he or she stays bought."48

Rather than being a fatalistic perspective, this frame was used to spotlight past votes and to suggest that in the wake of Columbine, it would be harder for politicians to stay in the pocket of the NRA. "It's going to be much more difficult for the NRA to dominate the Congress any longer,"49 said Sen. Paul Wellstone. After the Senate voted for some gun measures, Minority Leader Tom Daschle noted, "What you just saw is the NRA losing its grip on the United States Senate, at long last."50

We must do more to keep guns out of the hands of children and youth.

Appearing in 23% of the sample, this frame focused on the need to keep guns away from the young. Most policies being discussed were described as having the goal of keeping guns out of children's hands. As one editorial noted, "Measures such as these aim to reduce the availability of guns to children, making it more difficult for youngsters bent on slaughter to obtain the means to carry it out."51

Interestingly, some proponents embrace the effort to keep guns away from kids because the young are innocent victims — we must "give our children back their childhood"52 — and others because "trigger-happy teens" are the ones more likely to get involved in violence. As Senator Herb Kohn notes, "Whether a calculated crime or an avoidable accident, the more distance we put between kids and guns, the more senseless deaths and injuries we can prevent."53

The focus on youth seems to provide the middle ground that allows even gun control foes to agree with some policies. Gov. Frank Keating of Oklahoma says, "Even in a sportsman state like Oklahoma, people believe there are few if any circumstances when children should have unrestricted access to weapons."54 An Oak Lawn, Illinois village trustee says, "I cannot think of any reason in the world a child needs a weapon in Oak Lawn."55

We have too many guns, too easy to get.

Appearing in 21% of the sample, this frame focuses on the sheer volumes of guns in America as the source of the problem. As one mother of a murder victim puts it, "For some people it just comes down to numbers... I only know I lost my son and I live in a neighborhood where there are many, many guns."56

Proponents use analogies — some hyperbolic — to illustrate easy access to firearms: "Gun control will still get played around the edges, a little victory here, a little loss there, but in the end guns will still be easier to get than a six-pack of Bud."57 "When I went out to buy a gun one night, I had no idea it would be easier and less expensive than buying a pink cashmere sweater set."58

This frame is used to compare the U.S. to other nations where gun availability is more limited. A Minnesota report compares the state's homicide rate to that of Canada, and notes that two-thirds of homicides in the US involved firearms, compared with one-third of those in Canada. Director Rob Reiner, responding to Republican charges the violent movies are to blame, says "We have to stop the easy access to guns. Canada, Germany, Japan, England — every country gets our movies, but they don't kill anybody afterward."59

The people want gun control.

Sixteen percent of the sample included this frame, which asserts that the majority of the American public is in favor of laws to limit access to guns. Various polls show that "overall, roughly two-thirds of those polled support stricter gun control laws, compared with one-third who oppose them."60 This is portrayed as a fairly recent shift in public opinion, and one that is just beginning to be felt in political circles. As one reporter notes, "Gun control has become a winning political issue. In cities and suburbs, candidates who support gun control have won votes by insisting that being 'tough on crime' means being tough on guns. Police officials have stepped out to urge gun restrictions. It's hard to paint advocates of stronger gun laws as upper-class wimps when the men and women in blue are at their side."61 In another article, Johns Hopkins School of Public Health professor Stephen Teret notes, "Gradually over the past 20 years there's been a shift in perception about responsibility for gun violence, and the American public no longer ascribes that responsibility solely to the person pulling the trigger."62

The frame is also used to underscore the fact that many politicians are out of step with the American people on this issue. After the Senate rejected mandatory background checks at gun shows, Senator Paul Wellstone expressed amazement that the Senate had ignored public sentiment: "It raises questions about this disconnect between the Senate and the vast majority of people in the country on these questions."63

There is some suggestion within this frame that the shift may not be permanent, or the topic of gun control may not remain urgent for the public, as the memories of Columbine fade. "The Colorado shootings have for the moment galvanized public opinion,"64 one reporter writes (emphasis added). Rep. Rod Blagojevich notes, "We have a moment of opportunity here and we must seize that moment, while the eyes of America are watching us."65

How many deaths will it take before we say enough?

This frame, which appears in 15% of the sample, focuses on the emotional impact of lost lives and calls for action to put an end to the suffering. A mother who lost an 11-year-old in an Arkansas school shooting says, "It's not about the Second Amendment. It's about parents burying their children."66 Another mother says, "How many children must die before the gun lobby backs off and understands that parents don't want their children to have access to guns that can be used to hurt themselves and others?"67 "We must make Littleton a turning point,"68 Minority Leader Thomas Daschle says.

Others use this frame to try to put dramatic events like Columbine into perspective. "The number of innocent victims in Littleton is the same number of young people killed every day in America by guns, but no one pays much attention unless it's a mass killing,"69 parent Charles Blek notes. An interview with Congresswoman Carolyn McCarthy says, "'I'm here [in Congress] two and a half years and that means I've lost — what? — close to 13,000 kids,'70 the Congresswoman said of the 5,000 American minors who are shot to death annually, most of them without stirring national attention." Others cynically note, "Apparently, it will take at least a few more massacres for people to make Congress act instead of pretend."71

Other pro-gun control frames.

Other arguments supporting new gun policies appeared in less than 10% of the sample each:

- The gun industry should be held accountable for its actions (8%). "Gun manufacturers had a duty to prevent the sale of handguns to persons likely to cause harm."72 "The issue is bigger than any individual, and gun makers should shoulder a share of the blame."73 "The next step is for 'public opinion to seize the realization that the vast supply of cheap, readily available guns in the US is not a naturally occurring phenomena, but the result of decisions taken by businessmen who can be held accountable.'"74 "When it comes to luring innocent consumers to a deadly product, Joe Camel has nothing on the gunmakers."75

- Guns are a dangerous product that should be subject to safety standards (5%). "Children are killed or injured because manufacturers failed to install feasible locking devices."76 "A twoyear-old cannot open a bottle of aspirin because of its safety cap but can fire a gun."77

One equal opportunity frame: "Reasonable" gun measures

Some advocates we know never use the phrase "gun control" to describe the policies they support; instead, they say they are in favor of "reasonable gun measures." To find out whether this phrase is gaining currency and who is using it, we searched the text of the Nexis articles in the sample for the word "reasonable" and analyzed the results. Approximately 10% of the sample includes quotations using the word "reasonable" in reference to gun policies. But it is clear there is no agreement as to what the content of a reasonable gun policy might be, because different proponents apply the word to very different policies:

- Illinois Republican Senator Fitzgerald "insisted he was being unfairly maligned as a gunslinger: 'I do not believe that the Second Amendment is absolute and prohibits reasonable restrictions. As I've had a chance to look at individual proposals, I've found that a lot of them are reasonable.'"78

- A Des Moines Register editorial notes, "There is a legitimate distinction between handguns and long guns, and a reasonable line can be drawn between them."79

- In response to the defeat of a package of gun laws that would have established a statewide database to track gun buyers and made gun dealers liable for gun-related tragedies, Illinois state Rep. Tom Dart said, "I guess Illinois is just not ready for some reasonable gun-law restrictions."80

- "Reasonable regulations are not off the wall,"81 said Rep. Henry Hyde, who supported a waiting period to buy handguns and a ban on some semiautomatic guns. "It will be a battle to get them passed, but it can be done."82

In short, both sides seem to be using the phrase "reasonable gun policies" to associate the measures they support with the middle ground, and to paint their opposition as extremist.

Furthermore, in embracing the middle of the road, the term inherently describes incremental, not dramatic, change; it is the language of compromise, not revolution. Senator Paul Wellstone describes mandatory background checks as "quite reasonable and not all that far-reaching,"83 while Trent Lott's spokesman says that the mandatory sale of safety devices is "reasonable and... smacks of an appropriate compromise."84

Advocates should be aware of these implications of the phrase when deciding whether to use this language.

Discussion

This analysis reveals several concerns about news coverage of gun policies that will have critical implications for advocates.

Solutions covered: Framing research shows that the solutions covered in the news are often those granted most support by the public. In our analysis, there were a large number of possible policy solutions discussed. However, the dominant focus on the federal response meant that the policies covered tend to be of limited impact: mandating background checks at gun shows, for instance, is not likely to dramatically alter the landscape of deaths and injuries from guns. Also, most policies focus on the user; policies related to distribution or manufacture, one-gun-a-month, lawsuits, safety designs, or registration got relatively little coverage. Interestingly, proposals to ease CCW requirements also got relatively little coverage, especially post-Columbine.

Framing concerns: One of the most common frames in coverage of gun policies was that we must do more to keep firearms out of the hands of children and youth. The focus on children is a "winning" frame, which allows for agreement among those who may not agree on other aspects of firearms policies. However, this frame may be counterproductive in that it implies that guns are only a problem in the wrong hands. By enforcing a perspective that the identity of the user matters, this frame may ghettoize the problem and limit public support for more wide-reaching policies that would address all guns no matter who owns or uses them. By comparison, many tobacco control advocates feel that the focus on keeping cigarettes away from kids distracts policy makers and siphons support away from policies that would have a greater likelihood of reducing the effects of tobacco use among all age groups. Similarly, the use of the term "reasonable gun policies," while helpful in establishing common ground, may ultimately undermine broader gun policy efforts by diminishing support for more ambitious policies. Research is needed into how people understand and respond to these terms.

Countering pro-gun arguments: Those who oppose new gun policies rely on three primary frames, which can all be effectively countered by public health advocates.

- Enforce existing laws, don't make new ones. As Josh Sugarmann of the Violence Policy Center points out in one article in our sample, "The bulk of laws on the books try to address possession or point-of-retail sales. Few deal with the manufacture or distribution [of guns], and that's the big problem."85 Advocates need to educate the public about policies to control manufacturing and distribution of guns that could help reduce injuries and deaths. In another tack, advocates can also point out how Congress has systematically gutted the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms and underfunded its enforcement efforts, thus creating the low-enforcement situation these same members of Congress now decry.

- The problem isn't guns, it's criminals. This common argument fails to take into account firearms suicides, unintentional shootings and "non-criminal" shooters (first-time perpetrators), which together make up the vast majority of all gun injury and death cases. Policies that only restrict convicted criminals would fail to prevent the majority of shootings. Of course, many people make an emotional distinction between these and the victims of crime, making this a difficult argument to rebut. Painting the complete picture of gun deaths and injuries in a manner compelling to the public is one of the primary tasks of injury control advocates.

- The right to own guns is absolute. A large body of judicial rulings has failed to uphold a constitutional right of any citizen to own firearms. Advocates must understand the historical precedents and be able to articulate why the Second Amendment does not mean what the NRA says it does. At the same time, pro-gun advocates' use of this frame may work to the advantage of the public health side. In the wake of events like Columbine, those who would cling to an absolute right to own guns increasingly appear paranoid and dangerous. As one letter writer wondered, "Certainly they have a right to bear arms for self protection, but is a nation awash in guns really what the founders of this country had in mind?"86 As the public increasingly supports limits on gun availability, those who promote an unfettered right to bear arms are increasingly marginalized and their persuasive power diminishes.

This analysis shows the enormous agenda-setting power of an event like the shootings at Columbine; in our sample, fifteen pieces on gun policies were published in the six weeks prior to Columbine, while 155 appeared in the six weeks after. The tragedy at Columbine got America talking about what to do about guns in a new way. But in the newspapers, it is still mostly politicians doing the talking, often using gun policy debates to fuel their political blame games.

Advocates for public-health approaches to firearms policies must do more to promote their perspectives in news coverage. The unfortunate likelihood is that there will be another high-visibility tragedy such as Columbine that will focus the public's attention on guns. The challenge for advocates is to be prepared to leverage public concern into concrete action for the public's health. Advocates can do this by:

- mobilizing and training spokespeople, especially survivors of gun violence and victim's relatives, who so far have not been adequately represented in news coverage;

- speaking not just about the problem, but about solutions to gun violence, including policies that address manufacturing and distribution, not just possession and use; and

- reiterating that the American public supports reasonable gun policies.

Issue 8 was written by Katie Woodruff, MPH. Coding was done by Chaya Gordon and Elaine Villamin.

This Issue was supported by The Joyce Foundation with additional support from The California Wellness Foundation.

Issue is edited by Lori Dorfman, DrPH.

©2000 Berkeley Media Studies Group, a project of the Public Health Institute

References

1 Indiana already has such a law.

2 Kellermann A. et al. "Gun ownership as a risk factor for homicide in the home. New England Journal of Medicine, 1993; 329:1084-1091.

3 Rogers, E., Dearing, J., and Bregman, D. "The anatomy of agenda-setting research." Journal of Communication, 43(2):68-84, 1993.

4 These subjects are mutually exclusive categories. Percentages will not sum to 100% due to rounding error.

5 The percentages indicate the portion of pieces in which this type of speaker appeared. For example, several politicians could speak in a single article; in this table, each article is counted, not each speaker. More than one type of speaker could be quoted in each piece, so the percentages do not sum to 100%.

6 Percentages indicate the portion of pieces in which the policy was discussed. More than one policy could be quoted in each piece, so percentages will not sum to 100%. Policies mentioned fewer than five times were not included in this table.

7 The percentages indicate the portion of pieces in which this policy was discussed. More than one policy could be quoted in each piece, so the percentages will not sum to 100%. Policies mentioned fewer than five times were not included in this table.

8 The percentages indicate the portion of pieces in which this policy was discussed. More than one policy could be quoted in each piece, so the percentages will not sum to 100%. Policies mentioned fewer than five times were not included in this table.

9 The percentages indicate the portion of items in which that particular frame appeared. These frames are not mutually exclusive; several frames may have appeared in the same piece and therefore the percentages will not sum to 100%.

10 Rob Hotakainen, "Minnesota delegates debate pace, timing of gun-control plans; Some chagrined by House's slow pace," Star Tribune (Minneapolis, MN), May 31, 1999, Monday, Pg. 1A.

11 Representative Bill McCollum quoted in Frank Bruni's "House Democrats Push Stricter Gun Rules," The New York Times, May 28, 1999, Section A, Pg. 19.

12 Quoted in Associated Press' "More gun laws won't help, NRA figure says; Stricter regulations won't prevent school violence, the NRA's vice president said at a gathering of Georgia Republicans," Star Tribune (Minneapolis, MN), May 23, 1999, Pg. 13A.

13 Quoted in David Yepsen's "Buchanan jabs at Clinton's gun-control ideas," The Des Moines Register, April 29, 1999, Pg. 1.

14 Katherine Q. Seelye's "Terror in Littleton: The Gun Lobby; A Defiant N.R.A. Gathers in Denver," The New York Times, May 1, 1999, Section A, Pg. 12.

15 Frank Bruni's "House Democrats Push Stricter Gun Rules," The New York Times, May 28, 1999, Section A, Pg. 19.

16 Chuck Kuecker, "Gun Laws," Chicago Tribune, April 24, 1999, Pg. 26.

17 Quoted in Associated Press', "NRA says more gun laws won't prevent violence," Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, May 23, 1999, Pg. 16.

18 Kevin Michalowski, "School violence must stop," Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, April 22, 1999, Pg. 19.

19 Don Hasch, "School violence must stop," Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, April 22, 1999, Pg. 19.

20 Paul W. Demro, "The Register's Reader's Say," The Des Moines Register, May 18, 1999, Pg. 10.

21 Quoted in Katherine Q. Seelye's "Terror in Littleton: The Gun Lobby; A Defiant N.R.A. Gathers in Denver," The New York Times, May 1, 1999, Section A, Pg. 12.

22 James Jay Baker quoted in Katherine Q. Seelye's "Terror in Littleton: The Gun Lobby; A Defiant N.R.A. Gathers in Denver," The New York Times, May 1, 1999, Section A, Pg. 12.

23 Dave Tomlinson quoted in "In Canada, fewer guns and less violence," Star Tribune (Minneapolis, MN), May 16, 1999, Pg. 7A.

24 Wayne LaPierre quoted in Roberto Suro's "Industry Questioning NRA Role; In Wake of School Shootings, Group Struggles to Hold Loyalty," The Washington Post, April 25, 1999, Pg. A06.

25 Quoted in Craig Gilbert's "Senate backs handgun lock rule; Kohl-sponsored plan adopted 78-20, added to crime bill," Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, May 19, 1999, Pg. 1.

26 Spokesman for Sen. Rob Grams, Steve Behm quoted in David Westphal's and Tom Hamburger's "Clinton: Gun industry to back controls; He also calls on parents, TV to fight teen violence" Star Tribune (Minneapolis, MN), May 11, 1999, Pg. 1A.

27 Serafina Musial, "Letters to the Editor," The Washington Post, May 9, 1999, Pg. M02.

28 Quoted in Katherine Q. Seelye's "Campaigns Find All Talk Turns to Littleton," The New York Times, May 20, 1999, Section A, Pg. 24.

29 John S. Campana, "The Register's Reader's Say," The Des Moines Register, May 18, 1999, Pg. 10.

30 Jason Pilmaier, "Shooting in Colorado a wake-up call," Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, April 25, 1999, Pg. 5.

31 Senate Majority Floor Leader Mike Rogers quoted in Chris Christoff's and Dawson Bell's "Concealed-Gun Bills Advance Civic Leaders Vow Fight; State's OK Unlikely Soon," Detroit Free Press, May 27, 1999, Pg. 1A.

32 Larry Brown, "The Register's Reader's Say," The Des Moines Register, May 18, 1999, Pg. 10.

33 David Jaye, "Bearing Arms: More Permits Equal Fewer Victims," Detroit Free Press, May 26, 1999, Pg. 11A.

34 Ray Mason, "Senators Need to Hear Voices Other Than the NRA's," The Columbus Dispatch, May 26, 1999, Pg. 8A.

35 James Bass, "Carrying of Weapons Can Deter Criminals," The Columbus Dispatch, April 26, 1999, Pg. 8A.

36 David Hunt, "Biased Data on Firearms Only Confuse Arguments," The Columbus Dispatch, May 29, 1999, Pg. 15A.

37 Chuck Kuecker, "Gun Laws," Chicago Tribune, April 24, 1999, Pg. 26.

38 Jim Stingl, "No welcome mat waiting for NRA in Denver," Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, May 1, 1999, Pg. 1.

39 E.J. Dionne Jr., "Getting the Attention of Gun Manufacturers," Chicago Tribune, March 2, 1999, Pg. 15.

40 Kristen Olgren, "Shooting in Colorado a wake-up call," Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, April 25, 1999, Pg. 5.

41 Frank K. Hoover, "The Core Values of a Civil Society," Chicago Tribune, April 30,1999, Pg. 26.

42 Rep. Joel Brunsvold quoted in Christi Parsons' and Ray Long's "Daley Gun Bills Fail in Capitol; Democrats Join GOP in Turning Back Bid," Chicago Tribune, March 23, 1999, Pg. 1.

43 Maurice Sarfaty, "Don't allow local government to file anti-gun lawsuits," Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, March 29, 1999, Pg. 9.

44 ibid., 44.

45 "Disarm the NRA: GOP Must Free Itself from the Gun Lobby," The Columbus Dispatch, May 23, 1999, Pg. 2B.

46 Quoted in Associated Press' "Clinton Pushes Gun Law Passage; Democrats Huddle on House Action by Memorial Day," Chicago Tribune, May 21, 1999, Pg. 1.

47 From Tribune News Services, "House Democrats Vow to Push Hard in Gun-Control Effort," Chicago Tribune, May 22, 1999, Pg. 3.

48 Donald Kaul, "How low can Senate go?" The Des Moines Register, May 14, 1999, Pg. 13.

49 Quoted in Rob Hotakainen's "Gun controls pass; School violence adds urgency to Senate bill on juvenile justice," Star Tribune (Minneapolis, MN), May 21, 1999, Pg. 1A.

50 Quoted in Helen Dewar's and Juliet Eilperin's "Senate Backs New Gun Control, 5150," The Washington Post, May 21, 1999, Section A, Pg. A01.

51 The Columbus Dispatch, "Disarm the NRA; GOP Must Free Itself from the Gun Lobby," May 23, 1999, Pg. 2B.

52 Minority Leader Thomas A. Daschle quoted in Helen Dewar's "GOP Senators Stress Enforcement; Some Gun Curbs Embraced in Initiative Against Youth Violence," The Washington Post, May 12, 1999, Section A, Pg. A11.

53 Quoted in Frank A. Aukofer's "Mentioning killings, Clinton calls for tougher gun control," Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, April 28, 1999, Pg. 6.

54 Quoted in David E. Rosenbaum's "The Nation; The Gun Debate Has Two Sides. Now, a Third Way," The New York Times, May 23, 1999, Section 4, Pg. 3.

55 Quoted in Stephanie Banchero's "Village Will Consider Gun Ban for Those Under 21," Chicago Tribune, May 27, 1999, Pg. 7.

56 Freddie Hamilton quoted in Linnet Myers' "Go Ahead... Make Her Day; With Her Direct Approach and Quiet Confidence, Chicago Lawyer Anne Kimball Gives Gun Makers a Powerful Weapon," Chicago Tribune, May 2, 1999, Sunday, Pg. 12.

57 R. Bruce Dold, "Under the Gun; Voters Should Use Ballot Threat To Lobby Politiicians for Stricter Gun Legislation," Chicago Tribune, April 23, 1999, Pg. 25.

58 Maureen Dowd, "Liberties; Guns and Poses," The New York Times, May 9, 1999, Section 4, Pg. 17.

59 Quoted in Maureen Dowd's "Liberties; Guns and Poses," The New York Times, May 9, 1999, Section 4, Pg. 17.

60 Helen Dewar, "Senate Strongly Backs Child-Safe Devices for Guns; Senate Backs Child Safety Devices for Guns," The Washington Post, May 19, 1999, Pg. A01.

61 E.J. Dionne Jr., "Getting the Attention of Gun Manufacturers," Chicago Tribune, March 2, 1999, Pg. 15.

62 Quoted in Roberto Suro's "Industry Questioning NRA Role; In Wake of School Shootings, Group Struggles to Hold Loyalty," The Washington Post, April 25, 1999, Pg. A06.

63 Quoted in "Senate defeats plan for checks at gun shows; The prospects for passing major firearms controls dimmed with the rejection of the measure, seen as the least controversial of several gun proposals," Star Tribune (Minneapolis, MN), May 13, 1999, Pg. 13A.

64 Detroit Free Press, "Senate Republicans Rethink Gun Shows Vote Planned to Curb Unlicensed Dealer Sales After Public Backlash," May 14, 1999, Pg. 4A.

65 Quoted in Michael Ko's "Legislator Makes Case for More Gun Control; Blagojevich Urges OK of Background Checks," Chicago Tribune, May 24, 1999, Pg. 2.

66 Source unknown in R. Bruce Dold's "Under the Gun; Voters Should Use Ballot Threat To Lobby Politiicians for Stricter Gun Legislation," Chicago Tribune, April 23, 1999, Pg. 25.

67 Lt. Gov. Kathleen Kennedy Townsend quoted in Daniel LeDuc's and Jackie Spinner's "Starting Point For Governor's Gun Safety Bid," The Washington Post, April 29, 1999, Pg. M01.

68 Minority Leader Thomas A. Daschle quoted in Helen Dewar's "GOP Senators Stress Enforcement; Some Gun Curbs Embraced in Initiative Against Youth Violence," The Washington Post, May 12, 1999, Pg. A11.

69 Jim Stingl, "No welcome mat waiting for NRA in Denver," Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, May 1, 1999 Saturday, Pg. 1.

70 Quoted in Francis X. Clines' "Public Lives; Cold Candor on Shootings From Veteran of Gun Violence," The New York Times, May 10, 1999, Section A, Pg. 14.

71 Cathy Wilkins, "Minority rule? Amendment gives veto power to 41%," The Des Moines Register, May 30, 1999, Pg. 5.

72 Quote from Linten vs. Smith & Wesson (Chicago lawsuit) in Linnet Myers, "Go Ahead... Make Her Day; With Her Direct Approach and Quiet Confidence, Chicago Lawyer Anne Kimball Gives Gun Makers a Powerful Weapon," Chicago Tribune, May 2, 1999," Pg. 12.

73 ibid., 56.

74 Stephen Teret quoted in Roberto Suro's "Industry Questioning NRA Role; In Wake of School Shootings, Group Struggles to Hold Loyalty," The Washington Post, April 25, 1999, Pg. A06.

75 Sen. Barbara Boxer quoted in William Neikirk's "Gun Show Restriction Defeated in Senate," Chicago Tribune, May 13, 1999, Pg. 1.

76 Sharon Walsh's "Campaign Heats Up Against Gun Firms," The Washington Post, April 12, 1999, Pg. A01.

77 Wendy Koch's "Gun lawsuits triggering partisan showdown in Congress," USA Today, March 10, 1999, Pg. 5A.

78 Illinois Republican Senate candidate Peter Fitzgerald quoted in Mike Dorning's "Fitzgerald Shatters Gun-Backer Image," Chicago Tribune, May 16, 1999, Pg. 2.

79 The Des Moines Register, "Zero in on handguns; If the moment has come for gun control, handguns should be the target," April 28, 1999, Pg. 10.

80 Quoted in Christi Parsons' and Ray Long's "Daley Gun Bills Fail in Capitol; Democrats Join GOP in Turning Back Bid," Chicago Tribune, March 23, 1999, Pg. 1.

81 Quoted in Wendy Koch's "Gun-control efforts get more backing in Congress," USA Today, May 7, 1999, Pg. 3A.

82 ibid.

83 Quoted in "Senate defeats plan for checks at gun shows; The prospects for passing major firearms controls dimmed with the rejection of the measure, seen as the least controversial of several gun proposals," Star Tribune (Minneapolis, MN), May 13, 1999, Pg. 13A.

84 John Czwartacki quoted in Frank Bruni's "Republicans Giving Ground On Gun Control Amendments," The New York Times, May 17, 1999, Section A, Pg. 15.

85 Quoted in Katherine Q. Seelye's "Terror in Littleton: The Gun Lobby; A Defiant N.R.A. Gathers in Denver," The New York Times, May 1, 1999, Section A, Pg. 12.

86 Michael Shank, "Minority rule? Amendment gives veto power to 41%," The Des Moines Register, May 30, 1999, Pg. 5.