Issue 4: Children’s health in the news

Sunday, March 01, 1998Most people get most of their information about health and social issues from news. Thus the way we identify, define and respond to social and health issues is in large part dependent on how those issues are framed in the news. The purpose of this framing memo is to assess and help us understand the current news environment in which children’s health issues are portrayed.

A framing memo is a tool for understanding how an issue is presented and discussed in the news media. It analyzes the arguments and images people use to define and discuss an issue so that a blur of news coverage can be viewed in a methodical, meaningful way.

Based on editorial and news content of relevant news sources, the framing memo provides an analytic yet practical perspective on the arguments that shape news coverage. The purpose is systematically and efficiently to review public discussion surrounding an issue so the structure and complexities of the public conversation can be understood. A more traditional content analysis would determine the relative amount an issue appears in a given medium. In framing memos we are interested in “how” rather than “how much” of a subject is portrayed.

What we did

We searched three months of coverage (January through March 1997) from the Los Angeles Times, San Francisco Chronicle, Sacramento Bee, New York Times, USA Today and National Public Radio for all articles or opinion pieces that included in their headline or lead paragraph the terms “prenatal,” “preschool,” “early childhood development,” “well baby care,” “child care,” “day care,” “baby-sit,” and “family-friendly.” In addition, we took any items that included the terms “health care,” “Medicaid,” “asthma,” “immunizations,” “benefit,” “employ,” “insure,” “access,” “safety,” “discipline,” “learn,” “community-building,” or “work” if the item also included “baby/ies,” “toddler,” “infant,” “child,” “parent,” “mother,” “father,” or “family.” These key words were selected to give us a broad range of articles and opinion pieces on children’s health, both on specific health issues and on the issues of children’s well-being in the broader environment.

The key word search generated more than 3,500 titles. We reviewed those, and eliminated all items that were clearly not about children or children’s health. We selected for analysis all articles that appeared to be comprehensive explorations of major children’s health issues: for example, we selected pieces on violence in schools; we did not select pieces on specific violent crimes.

We coded each of the selected pieces for whether it was news or opinion, its primary subject, whether it mentioned a specific age group, who was quoted in the piece, and what solutions were advanced, if any, to the issues discussed. At least two people read each piece to identify themes and frames.

What we found

The vast majority (94%) of the 3,500 titles were not directly about children’s health. For example, articles with references to a “parent company” or a description of a wildlife preserve program as “day care for baby seals” met the criteria for the key word search, even though they were not about children’s health. This shows that children or the concept of family appear far more often in news and opinion as metaphors than as real life figures or issues.

Only 201 pieces substantively addressed children’s health. Of these, the majority (77%) were news articles or features; the remainder were letters to the editor, editorials, op-eds and talk radio transcripts. The most prolific source on children’s health was the Los Angeles Times, with 69 pieces. During the three-month sample period National Public Radio aired six pieces on children’s health.

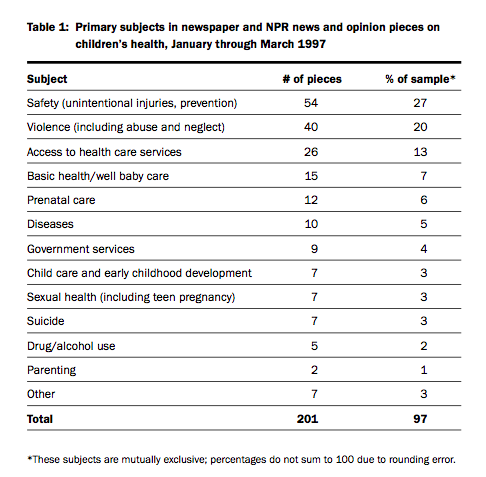

The most common subject found in our sample was child safety (27% of the sample). The next most frequent child health subjects were violence, including child abuse and neglect (20%), access to health care services (13%), general health and well baby care (7%), prenatal care (6%), and various diseases (5%). All other subjects each accounted for less than 5% of the sample (see Table 1 below).

To flesh out further quantitative data that could shed light on how children’s health is currently reported, we looked at the ages of children covered, solutions presented, and speakers quoted in the sample:

Ages of children covered

While we searched for key words that would identify stories about the health of young children in particular, nearly half of pieces (48%) did not specify the age of children affected by the issue. Among those that did differentiate, one-third of the pieces focused on children ages 12 and under; 6% covered youth ages 13 and up. While most news articles discuss young people in general terms rather than by specific age groups, when writers do specify ages, younger children appear to be far more newsworthy than teens.

Solutions presented

Agenda-setting research demonstrates that the subjects covered in the news are those to which the public is likely to pay attention. Thus we wanted to know what solutions to the problems of children’s health were portrayed (see Table 2). The largest bulk of pieces (23%) did not present any solutions at all; they merely described problems or issues. When an approach for solving or preventing a problem was discussed, it was most commonly in the form of information to parents about what they could do to protect their children (19%). These included, among others, stories on installing child safety seats in cars, keeping children from drowning in backyard pools, recognizing the signs of gang membership, talking to kids about alcohol and drug use, monitoring TV and Internet use, keeping kids from choking on latex balloons, and reducing the impact of parental “workaholism” on kids.

The next most common solution covered in our sample, appearing in 15% of the sample, was to expand access to health care for uninsured children. All other solutions appeared in fewer than 10% of pieces each. Not all solutions reflected a public health approach. For example, the largest category of “solution” was tips for parents on how to avoid a problem or how to respond once the problem presents itself. While this is certainly important information for parents to have, it is a very limited approach to addressing children’s health problems. Consider child safety seats: experts estimate that a population or public approach to require car makers to adopt a uniform mechanism for attaching child safety seats in cars could prevent 200 child deaths each year. Educating parents about proper installation of the current variety of seats is still necessary, but not nearly as effective as a uniform attachment standard would be. Yet the debate over standards for safety seats was rarely covered in our sample.

Who speaks

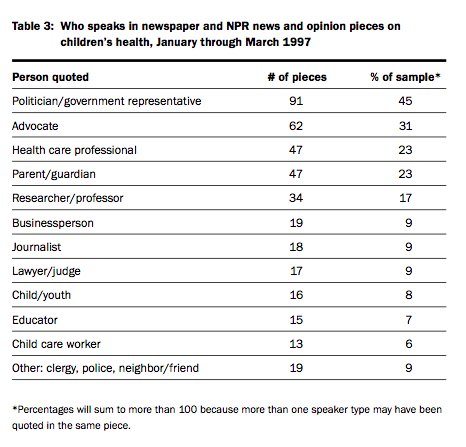

Knowing what types of people were quoted in coverage of children’s health is important because it suggests where journalists turn for information and outlines the perspectives that are represented. The sources quoted most often were politicians and other government representatives, quoted in nearly half (45%) of the pieces (See Table 3). Advocates spoke in about a third of the pieces, with health care professionals and parents each quoted in about a quarter of the pieces. Children or youth themselves were quoted in 8% of the pieces. Most of these stories where young people spoke were about problems, rather than solutions: six were on violence, with children and youth talking about their fears about gangs and safety; four included children remembering playmates who had died (three in a school bus crash, one killed by a rare infectious disease); three featured youth talking about alcohol and drug use. Only one piece quoted a young person talking about a positive program: a news feature on an after-school program for disabled kids.

Frames on children’s health

News is organized, or framed, in order to make sense out of many-sided and subtly shaded issues. Inevitably, some things are left out of the frame while others are included. Similarly, some features may be pushed to the edge of the frame, while others remain more central. The frame is important because whatever facts, values, or images are included are accorded legitimacy, while those mentioned at the fringe or not included are marginalized or left out of public discussion. The frame will significantly contribute to how the issue is considered and talked about by the public. As Charlotte Ryan notes, “each [frame] has a distinct definition of the issue, of who is responsible, and of how the issue might be resolved.”1

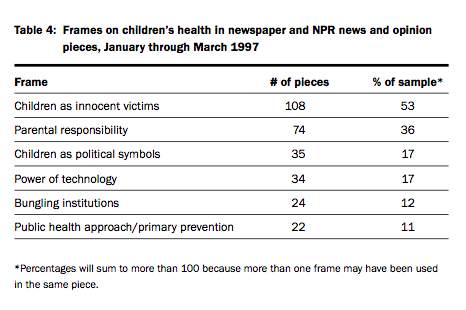

Several key frames emerged in the newspaper and NPR coverage of children’s health. First, children are seen as innocent victims, and parental responsibility is portrayed as the primary way of preventing their victimization. Children are also used as political symbols. A great deal of faith is placed in the power of technology, while much criticism is leveled at bungling institutions. The public health approach to children’s health and safety appears in a few rare but significant pieces. Finally, the debate over expanding access to health care for uninsured kids highlights several of these frames. (See Table 4.)

Children as victims

In our sample, it was clear that children are presented as perhaps the only population still deserving of public support in our society today. More than half of the pieces (53%) portrayed children as vulnerable innocents needing to be protected. Heartbreaking stories of child abuse and tragedies of children injured and killed in car crashes abound. As one letter writer claims, “it is our responsibility to protect children, who cannot speak up for themselves.” The frame stirs and plays on sympathy for children; yet the prevalence of this frame seems to obscure less dramatic but more common children’s health issues such as asthma, immunizations, and well baby care.

Parental responsibility

Despite the familiar refrain “It takes a village to raise a child,” our sample shows that news coverage primarily addresses the parents’ responsibilities for children’s health and safety. More than one-third (36%) of pieces either described what parents could do about a children’s health or safety problem, or, if not giving specific tips, at least asserted that the parents were responsible. The most common solution covered was in the form of information and advice for parents. For example, only four of the stories on violence talked about gun control; far more discussed what parents can do to help kids avoid violent confrontations. Similarly, a story on alcohol talked only about how to help kids say no to alcohol, rather than describing any policies designed to reduce alcohol’s availability to youth. While information for parents is important, the overwhelming focus on parental responsibility may diminish public understanding of and support for broader policies.

Children as political symbols

Many of the pieces in our sample, while nominally covering children’s health issues, were really more about the politics behind the issues. Thus, children were used as symbols in a political struggle; this frame was present in 17% of the sample. For example, a story on children’s services in the state of New York described how Governor Pataki was getting political mileage out of restructuring the departments providing children’s services. The article was not about the benefits to children but to Pataki. Similarly, a story about a teen pregnancy prevention program describes the political battle to keep the program funded, rather than the services or benefits of the program; a letter about a local birth center criticizes HMO funding policies. A columnist criticizes President Clinton for his plan to insure children, calling it a “politically tempting way to impose universal health care on the public. Start with kids ÛÓ who can say no to children?” This reports on the political horse-race perspective on children’s health, without providing substantive discussion of the stakes for children and their families.

The power of technology

Our sample reveals an inordinate faith in the power of technology to help keep children healthy and safe, with this frame included in 17% of the sample. Articles tout a wide range of gadgets to help “baby proof” the home, from the traditional outlet plugs to complex toilet latches and infrared beam alarm systems to detect baby toddling out the door. Other articles are devoted to the proper installation of car seats and the appropriate settings for air bags to reduce injuries to young children in car crashes. Parents interviewed in our sample also put enormous stock in the power of the CD-ROM lists of convicted child molesters mandated by “Megan’s Law”; as one parent says, “If this computerized list can help keep our kids safe, I’m all for it.” This frame reflects the American appetite for technological saviors and silver bullets. By contrast, the lower-tech intervention of bicycle helmets, which reduces risk of injury more than car seats do, was covered in only one story in our sample.

Bungling institutions

Because the desire to protect children seems universal, the outrage is particularly strong when institutions fail to do so. The failure of child protective and other services is so common a theme as to be almost a story character in itself: the bungling institution, which appeared as a frame in 12% of the sample. For instance, New York City’s child welfare agency is criticized for “concealing its mistakes and failing to hold workers accountable” in the cases of 8 abused children; the article says that the agency “described in graphic detail yesterday an array of errors and oversight.” Agencies are criticized for giving abused children into the care of other relatives without properly investigating whether the relatives are themselves safe caretakers; “That’s not bad relatives, that’s bad social work,” one observer notes. The flood of cases overwhelming social workers is seen as a contributing factor but it does not seem to engender sympathy for the institutions. Interestingly, the institution of the police is seen as heroic in these articles, as in several pieces where police are the ones to find neglected children and alert the child protective workers (who are subsequently revealed to have let the case slip between the cracks). This frame highlights journalism’s tedency toward extremes. Horrific cases of government institutions failing are reportedÛÓas well they should beÛÓbut similarly weighty reporting is not provided in the more frequent but less sensational cases, nor is there much attention to the circumstances that might prevent the tragedies.

The public health approach

A public health approach sees health problems as interactions between individuals and the environments in which they live. Whether the environment is safe and “health-producing” is determined in large part by the policies and rules that shape the environment. Those policies and rulesÛÓin addition to personal behaviorÛÓbecome the focus of public health attention. Therefore, public health approaches typically are broader than efforts to change personal behavior and efforts to provide medical or social services.

While most articles did not include a public health approach (the frame was included in 11% of the sample), there were several key articles that are worth noting in this theme. Generally, articles containing a public health approach followed announcements or actions by government agencies or public health researchers. For example, the EPA announced that it was heightening pollution controls to ease the health problems of children with asthma; “From now on, we will take into account the unique vulnerabilities of children,” the spokesperson said. A handful of other articles on environmental factors contributing to asthma followed this announcement. Similarly, a report on the effects of secondhand smoke on children, and another on the failure of an intervention with low birthweight babies, were generated by the publication of scientific studies on the topics. Other stories followed government action to replace dangerous playground equipment and regulate air bag velocity to protect children. It seems that public health professionals and government regulators have the power to set the agenda for journalists, but that journalists do not seek out coverage on these topics without major developments emanating from these professionals.

The debate over health insurance for children

The debate over providing health care access to uninsured kids composed 15% of our sample, and the arguments on the issue highlight several of the above frames. Advocates for expanding health care access cite the “worsening crisis” of uninsured children, claiming that leaving children without health insurance is “not good for children and not good for society.” It seems widely accepted that universal health insurance is a dead issue in the U.S., but that children at least are worthy of such protection. Indeed, several writers make a further distinction about the worthiness of these children, pointing out that their parents work hard and yet the children of welfare recipients get better health care. The faith in technology is demonstrated in the belief that if children just had access to better health care, they would be healthier. This reflects a dominant popular belief that health care is equivalent to good health, despite research that shows that access to health care services accounts for less than 10% of health status.2 Finally, pro-insurance advocates note that paying for basic health care, such as prenatal services, is far cheaper than paying for emergency medical treatment such as neonatal intensive care services. This appeal to practicality, and the fact that President Clinton’s health care proposal is “modest,” insuring only half of the currently uninsured, seem to be powerful in framing the health care policy as a moderate, mainstream solution.

On the other side, opponents to the health insurance proposal cite a different kind of “bungling institution” in their arguments: the “big government” of federal regulations and tax laws, which have “inflated health insurance costs while forcing insurers to play Scrooge.” The short- sightedness and bloat of the federal government, they claim, is the real reason so many families can’t afford market-rate insurance. The parental responsibility argument also comes into play: opponents note that “lack of insurance is no indicator of helplessness”; since many of these families make $30,000 or more, they suggest that parents could afford insurance if they adjusted their priorities. Finally, one commentator, noting that most uninsured children are in California, Texas, Florida and Arizona, concludes that the problem is not really a national problem but a “border phenomenon,” thereby implying that some children are more worthy of protection than others.

It is important to note that while we discuss both sides of the debate here, the news coverage was considerably more one-sided. Out of 30 pieces on the topic, only three were predominantly anti-insurance; the others touched on concerns about how to pay for the program but by and large were in favor of insuring children if at all possible.

Implications

This analysis reveals relatively little substantive coverage on important children’s health subjects in our major news sources. We were disappointed, after identifying more than 3,500 titles, to find only 201 pieces that met the criteria for in-depth analysis.

Children and youth are quoted directly in only a handful of pieces; newspaper and radio seem to provide fewer opportunities for youth voices than TV does.3 This is challenging for those who want to get youth involved as advocates and spokespeople; hearing directly from young people could increase public opinion of and support for children and youth generally and may be an additional fresh source for journalists.

The focus on parental education in the pieces on children’s health is of some concern. Of course parents need to know what they can do to protect their children, and journalists have typically seen this kind of education as one of their primary tasks. However, news that predominantly fails to discuss solutions or describes only what parents can do will reinforce individual-level approaches; it is not likely to help expand support for broader social or public health policies. In this sample, stories on child safety seats were far more likely to tell parents how to install the seats properly than to explain the campaign to make manufacturers adopt a uniform standard so that all seats would be easier to install. These stories fail to illustrate the wide range of important policy decisions that could potentially help all parents do a better job keeping their children healthy and safe.

Recommendations

Despite these concerns, many opportunities exist for better informing the public on children’s health issues via the news. First, the coverage of legislation aimed at expanding health insurance coverage for children has raised the issue of children’s health on the agenda. This is an opportunity for health stories to get the same prominence that education, parenting and other issues receive. In addition, the high proportion of news and feature stories (77% of our sample) indicates that advocates have an opportunity to increase their direct participation in the debate, in the form of more op-eds, letters to the editor and editorial board visits to solicit editorials.

The image of children as innocents needing to be protected is a strong theme in journalism. Children’s advocates could capitalize on this theme in promoting stories that show what government and other institutions could do to protect children.

Recommendations for public health advocates

Public health advocates are sometimes frustrated by the limitations of news coverage on chil- dren’s health. Certainly we were disappointed that so few pieces in this sample had substantive discus- sions of the issue. Advocates should be aware that some of the most prominent reporting on children’s health issues is emanating from the political or government beats, not the health or family beats. These reporters are not necessarily experienced with reporting on children’s issues, so the onus is on advocates to be sure reporters have the background information they need to understand the issue within the constraints of their tight deadlines.

Make data available, and make it meaningful.

Health practitioners can help journalists produce more comprehensive reports by giving them data and helping them understand the epidemiology of children’s health. The data must be accurate, localized, easily understandable and linked to specific problems. For example, advocates releasing a report on the lack of appropriate infant care in California described the cost of day care in terms of percent of a minimum wage salary as well as the average salary in each California county. This made it easier for reporters to make the data understandable and compelling for their audiences.

Help reporters find contacts.

Journalists need people through which to tell stories. Help them find appropriate spokespeople who can offer facts and opinion about children’s health issues. Look beyond the traditional sourcesÛÓagency directors, supportive politiciansÛÓto include parents, children, educators, child care providers, clergy and others with a stake in the issue. Be sensitive to journalists’ deadline pressures and accommodate their need for a quick response.

Participate in the public conversation.

Encourage families and advocates to share their knowledge and experience and express their opinions in letters to the editor and op-ed pieces.

Recommendations for journalists

Journalists’ role is to inform the public and policy makers on key issues. Typically, they approach this task by asking probing questions of credible and informed sources. Therefore, our recommendations for journalists center around which sources they seek and what questions they are asking of them. Our society depends on journalists to penetrate beyond the surface to expose the meaningful aspects of issues. Since many issues compete for journalists’ attention, we recommend journalists do the following to increase attention to children’s health issues:

Ask “What should be done, beyond parental action?”

Solutions to serious problems are complex. What part is most important? According to whom? What is being done so far, and by whom? What still needs to be done? What agencies could be working together better? It is important to report institutions’ attempts at improvement, as well as their glaring failures.

When telling a family’s story, go further.

Ask “Why does this matter to the community, not just this family?” What are the long-term ramifications of this issue? What programs or people are working to improve things for this family and others like them?

When politicians use children to gain sympathy for their positions, follow up.

Do they carry out their promises? Do they try? What hinders progress?

Don’t wait for a crisis.

Gather background information on children’s health issues so you are better prepared when the issue comes up. Determine the status of children’s health in your community. How does it compare to other communities? To national data? What is happening elsewhere in the country on this issue? What are the long-term implications of the issue on the overall societyÛÓon schools, the legal system, the social system? When other local issues are being debated, ask, “What does this mean for children and families?”

Issue 4 was written by Katie Woodruff, MPH; coding was done by Alyson Geller, MPH and Elaine Villamin, BA. Edited by Lori Dorfman, DrPH, and Lawrence Wallack, DrPH. We thank Debra Gordon, 1997 Kaiser Media Fellow and medical reporter for the Virginian- Pilot, for her comments on an early draft. Funded by the California Endowment. A preliminary version of this research was presented on November 14, 1997 to Sound Partners for Community Health, a program of the Benton Foundation funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Issue is published by Berkeley Media Studies Group, a project of the Public Health Institute.

References

1 Ryan, Charlotte. Prime Time Activism: Media strategies for grassroots organizing. Boston: South End Press, 1991.

2 Adler, N. E. et al. “Socioeconomic Inequalities in Health,” JAMA, 269:24:3140- 3145, 1993.

3 Dorfman L. and Woodruff K. “Local TV news, violence and youth: who speaks?” Prepared for Media Matters: The Institute on News and Social Problems, published by The Benton Foundation, Washington DC, Sept. 1995.