Issue 20: Struggling to breathe: How a health department is working with community members to reduce air pollution and improve health equity in Oakland

Thursday, October 25, 2012If you search the web for articles on ways to improve health, headlines touting the benefits of a better diet and increased exercise will likely top the list. You might also see suggestions like, “get plenty of rest,” “drink more water,” or “limit caffeine and alcohol.”

But if you approach Sandra Witt, former deputy director of policy, planning, and health equity for the Alameda County Public Health Department in California’s Bay Area, with the same question, her response might surprise you. Health, she’ll tell you, begins long before you start your morning jog. Health often stems from where you live.

In fact, where people live can matter more than personal behavior or even genetics in influencing how healthy they will be and how long they will live. Our surroundings affect what educational opportunities we have, how much money we make, how clean our water is — even the pollution levels we’re exposed to. And each of these things can help or harm our health, regardless of how well we eat or how much we exercise.

At the population level, when barriers to health become more concentrated in some communities than others, the consequences can be devastating. Such barriers can result in greater absences from school and work, higher rates of disease and disability, more trips to the hospital, and an increased risk of premature death. They can cause the babies born in one zip code to have lower birth weights than those born just a few miles away. Or the children in one neighborhood to be at greater risk of developing asthma than those in an adjacent part of town.

Still, these differences in our communities — and resulting disparities in health and mortality — don’t just happen. They stem from decisions that individuals and institutions make that, intentionally or not, advantage some groups while disadvantaging others and, over the long term, manifest themselves in our bodies. Called health inequities, they are systemic, unjust and preventable. And public health departments across the country are realizing that, to be as effective as possible, they need to pay attention to them.

This is the story of one neighborhood’s struggle to tackle the underlying causes of such inequities. It is also the tale of how a public health department is taking innovative steps — such as partnering with community groups and building internal capacity — to join in that struggle to reduce and prevent inequities, and how other health departments can do the same.

Unequal health in Oakland

Situated along California’s coastline, Oakland is the state’s eighth largest city. It is known for its rich history of sports and culture, ethnic diversity, and ongoing political activism. The city has a mild climate, with clear, sunny skies the majority of the year. And it is a perfect spot to take in some local jazz or panoramic views of the Golden Gate Bridge. The New York Times named Oakland fifth on its top 45 list of places to visit in 2012, citing sophisticated restaurants and a newly reopened Fox Theater as two of the city’s main draws. A shipping hub, Oakland is also a major economic engine and conduit for international trade. It is home to the country’s fifth busiest container port, moving cargo for some of the world’s largest retailers like Wal-Mart and Costco.

But there is a flip side to the city’s reputation: Oakland frequently makes national headlines for its high rates of violence and struggles with racial and economic inequality. On New Year’s Day in 2009, for example, a white police officer working for Bay Area Rapid Transit, the area’s subway, shot and killed an unarmed black man who was lying facedown on a subway platform in Oakland.

While the community decried through peaceful protest what it saw as a racially motivated act, the media focused on the actions of a small group of people who turned to violence. On January 7, 2009, a few rioters torched cars and broke the windows of local businesses. Over the course of the next year, other mostly peaceful protests were also tinged with violence, and mass media devoured the story, often creating an overly simplified portrait of Oakland as a place where people have to live in fear of being killed.

A similar theme of violence runs through mainstream media coverage of Occupy Oakland, the city’s demonstrations as part of the Occupy Wall Street movement against social and economic inequity. Although many of the protests have been nonviolent, stories of chaos, vandalism and bloodshed fill the news. When a January 2012 demonstration involving police-civilian skirmishes and tear gas culminated in mass arrests, journalists were quick to the story, wagging a scolding finger at the city of Oakland and its residents. After seeing TV footage of the protest, one writer described the scene as “more like a civil war than a nonviolent march.”1

This is the Oakland that the mainstream media hold up to the rest of the nation. Headlines alternate between casting the city as a cultural mecca and crime-ridden catastrophe. And in the process, an important piece of the story too often gets overlooked: the real-world effects the city’s complex environment has on the people who live there.

In particular, Oakland’s social and political climate affects the health of its residents and workers, who have strikingly different rates of death and disease, depending on what part of the city they live and work in. A white person born in the Oakland Hills, an affluent part of the city, can expect to live 15 years longer than an African-American born in West Oakland. As a baby, that same white person from the hills is 1.5 times less likely to be born premature. As a child, he or she is 2.5 times less likely to be behind in vaccinations, and as an adult, three times less likely to die of a stroke.

These startling statistics come from a report the Alameda County Public Health Department (ACPHD) published in 2008 called “Life and Death from Unnatural Causes: Health and Social Inequity in Alameda County.”2 These differences are not random, the report explains. Nor are they the result of any biological difference between blacks and whites. In fact, black-white differences in life expectancy weren’t always so great. Data gleaned from death certificates show that in the 1960s in Alameda County, the disparity was minimal.3 Since then, however, social and health inequities have continued to grow. This trend is the consequence of both historical and present-day laws and practices that have fueled racial segregation and perpetually restricted the power, opportunity and resources available to the mostly low-income, black residents of West Oakland. At the same time, they have advantaged the mostly white, affluent residents living in the Oakland Hills.

For example, in the 1950s, the city of Oakland wanted to find a way to connect the southern part of Alameda County to the Bay Bridge, allowing people to travel to downtown San Francisco more easily. So they developed plans to build a two-tiered overpass called the Cypress Street Viaduct that would lead traffic from city streets onto the interstate. The trouble was, they built it through the middle of West Oakland, bisecting the region and displacing hundreds of residents and dozens of businesses. The viaduct cut off a substantial portion of West Oakland from downtown, isolated the community, and increased residents’ exposure to noise and air pollution.4

Community residents and activists later prevailed in getting traffic rerouted around the city after the viaduct collapsed in the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake.5 This speaks to the community’s strength and resilience in spite of great obstacles; however, the area remains blighted and continues to struggle against other inequities.

Not surprisingly, then, the people who are more likely to have a home that captures those panoramic views of the Golden Gate Bridge and those who are more likely to encounter police brutality typically are not one and the same. They may live just miles apart and claim the same city as their home, but Oakland’s low-income people of color and their wealthy white counterparts inhabit starkly different worlds. Current policies and systems mean that they have different options for where they send their kids to school; get exposed to different amounts of marketing for tobacco, alcohol and junk food; encounter different degrees of discrimination; and even breathe different air.

And for the low-income, black Americans (and increasing numbers of Latinos, Asians and Native Americans) in Oakland whose schools are poorer, healthy food options are fewer, experiences with racism are greater, and air is more polluted, these conditions add up to greater amounts of stress, which has physiological consequences. The constant elevation of stress over time can harm all major organ systems. It can raise blood pressure, increase heart rate and spike levels of cortisol, a key hormone that affects immune function. Too much cortisol over long periods of time can impair mental function, inhibit children’s development, and lead to a variety of chronic diseases.6In other words, it can devastate health.

ACPHD’s report goes on to detail the social, economic and political causes of health inequities, not just for those living in Oakland, but for everyone. And it shows that if you want to improve health for entire populations, then those root causes are where you have to intervene which is exactly what ACPHD is doing. The health department is using a combination of media advocacy, internal capacity-building, and collaboration with residents, community groups and other government agencies to increase awareness about health inequities and to combat them. Ultimately, ACPHD recognizes that although the story of health inequities in Oakland is a daunting one, it has an upside: It can unite people to work together for real change.

Seizing an opportunity for action

The Alameda County Public Health Department has long had a focus on understanding why some people get sick more and die sooner than others. And as its report “Life and Death from Unnatural Causes”7 reflects, it keeps its eyes open for opportunities to act.

So when, in 2007, leaders from the West Oakland Environmental Indicators Project (WOEIP), a community group that, among its many efforts, was working to reduce diesel pollution and related health risks near the port in West Oakland, approached leaders at ACPHD and asked them to join the effort, it didn’t take much convincing for ACPHD to say yes.

Both groups knew that West Oakland has the highest mortality in Alameda County. Of the 15-year life expectancy gap between African-Americans born in West Oakland and white people born in the Oakland Hills, 14 of those years come from an increased burden of chronic disease8 — not infectious disease, injury or violence. West Oakland has the highest rates of coronary heart disease, congestive heart failure and emphysema.9 It also has the highest rates of asthma, with West Oakland children ages four and younger visiting the emergency room at a rate that’s nearly three times the county average.10

WOEIP and ACPHD (as well as numerous community organizations like the East Bay Alliance for a Sustainable Economy) also knew that much of West Oakland’s higher burden of asthma and other chronic disease relates to the area’s heavier exposure to air pollution.11 Highly trafficked interstates border West Oakland. And the community shares real estate with the Port of Oakland, whose continued movement of goods on thousands of trucks and ships keeps the air thick with diesel smoke.

Truck traffic through the port has more than doubled since 2000, and port officials expect overall container volume to double by 2025.12 While waiting to pick up cargo, trucks often idle for hours on local streets. Soot lines the windowsills of nearby homes, and asthma inhalers fill too many residents’ medicine cabinets. And port truck drivers, who work an average of 11 hours each day and typically lack health insurance, continually breathe concentrated diesel pollution, putting them at increased risk of lung cancer and other respiratory diseases.13

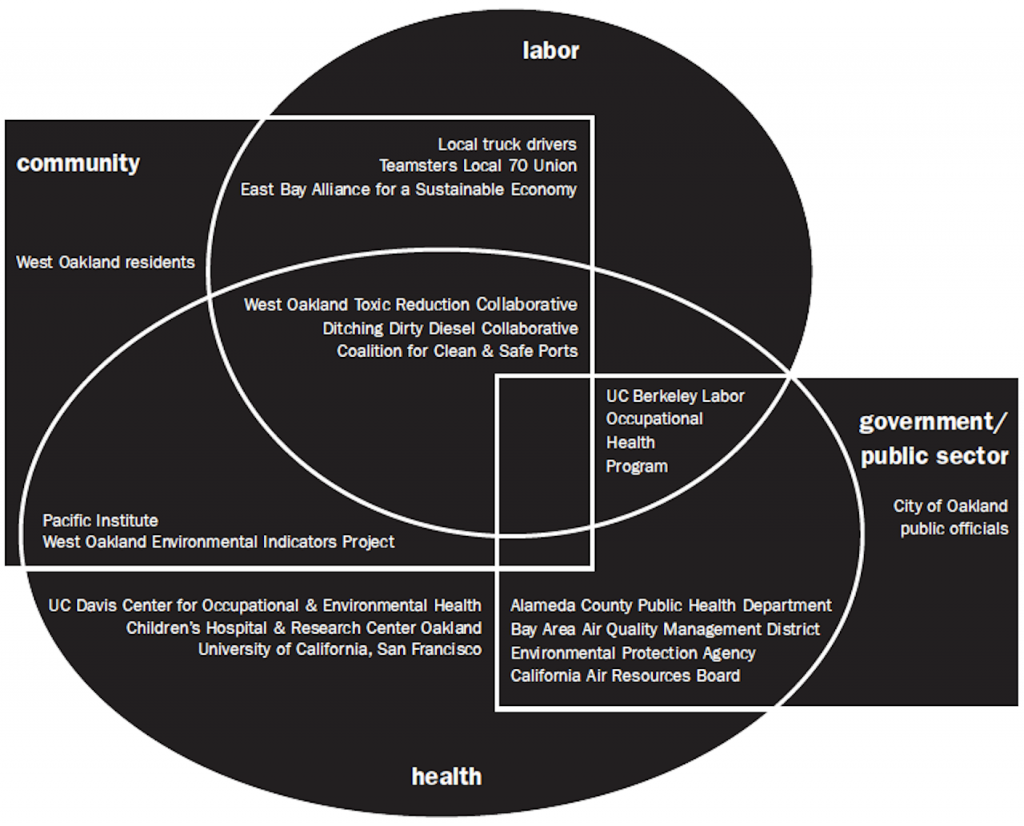

The connection between air pollution and health was no secret to the West Oakland community. Concerned, residents called for change and the West Oakland Environmental Indicators Project took action. WOEIP (whose director, long-time community activist Margaret Gordon, was then a commissioner at the port) worked along with other community stakeholders including the Coalition for Clean & Safe Ports and the Ditching Dirty Diesel Collaborative to persuade the Port of Oakland to put together a task force to help create a policy framework for improving the community’s air quality. The task force was composed of a wide range of groups including West Oakland residents, environmental regulatory agencies, labor unions, community advocacy organizations, shipping companies, health agencies and other business stakeholders. The idea, then, was to give the Alameda County Public Health Department a seat at the table so that it could support the group’s work with additional health data, help set policy goals, and push the port to implement them.

It wasn’t the first time that ACPHD had worked with community groups to tackle a complex issue. It wasn’t the first time ACPHD and WOEIP had worked together to advance health equity either. In fact, over the last decade, WOEIP and ACPHD have tackled issues as varied as affordable housing and indoor air pollution. But what made the port work unique was its position at the intersection of complex labor conditions. Specifically, the health solution that the Coalition for Clean & Safe Ports, WOEIP, ACPHD, and a segment of the task force were advocating involved a critical but contentious labor solution to ensure that low-income immigrant drivers would not have to shoulder the cost of purchasing new clean-fuel trucks. And this complexity makes it a prime example of how a public health department can infuse a focus on health equity into its daily practice in spite of large obstacles.*

Making the connection between labor and health

The connection to labor disputes begins more than 30 years ago during the nationwide deregulation of the trucking industry. With the passage of the Motor Carrier Act of 1980, the industry began its transition away from strong union jobs. Port trucking companies that once paid a living wage and provided port drivers with pensions, health insurance, and a say in their work began denying new hires benefits and forcing them not only to work for less money but also to purchase and pay for the maintenance of their trucks. A 2010 port trucking industry survey shows that many trucking companies have also illegally misclassified their employees, with approximately 82 percent of the nation’s 110,000 port drivers now being treated as independent contractors.14

By 2007, the year the task force convened, Oakland’s port trucking system — like many others — had become unsustainable and harmful to health, with poorly maintained trucks spewing diesel pollution into the air. Looking to address the issue, the California Air Resources Board passed a regulation requiring trucks servicing any state port to meet aggressive new emissions standards.

Yet Oakland’s port drivers, most of whom were — and still are — overworked and receiving poverty-level wages15 (a quarter make less than $7.64 per hour16), could not afford the cost of retrofitting or replacing their rigs with newer clean-fuel trucks. Complicating matters, the Port of Oakland had not enacted a mechanism to set industry standards, so port trucking and shipping companies had grown accustomed to reaping profits without having to pay the real costs of moving goods through the port and through West Oakland. This left community residents and port drivers to shoulder the financial and health burden of moving cargo.

To be successful, any of the task force’s efforts to clean up the air surrounding the Port of Oakland would have to also help shift the balance of power within the port trucking industry. Drivers would need better working conditions and more say over their jobs, and port commissioners, who manage the port’s operations, would need greater control over setting port trucking standards. To this end, one potential solution lay in the development of a Clean Truck Program, which the Coalition for Clean & Safe Ports, members of whom participated on the task force, had been encouraging port commissioners to adopt even prior to the task force’s formation.

Under a Clean Truck Program, companies wanting to service the port would have to first sign concessionary agreements with the port. Each agreement would function like a lease and include certain standards, including that trucking companies hire drivers as employees rather than misclassifying them as independent contractors. Additionally, port trucks would have to be clean and use the best available technology to reduce diesel pollution, and port trucking companies would be required to follow strict truck routes placed outside of residential neighborhoods. Although some routes do currently exist, they are not well enforced.

In recent years, the Port of Los Angeles, the busiest container port in the nation, has shown that having a Clean Truck Program works. It implemented such a policy in October of 2008 with a goal of reducing truck emissions 80 percent by 2012.17 Emissions data show the port surpassed that goal a year ahead of schedule.18

The Clean Truck Program illustrates the interconnections between labor, community, the environment and health. For example, without improvements in labor, health goals will languish and vice versa. So when the Alameda County Public Health Department’s leaders said yes to the invitation to help clean up operations at the Port of Oakland by participating on the task force, they knew the process would be intense and messy. They also knew it would be well worth it. On both counts, they were right.

A two-year process

Beginning in 2007, the task force met regularly for two years. Its charge: to identify goals for a Maritime Air Quality Improvement Plan — including a plan to reduce emissions coming from port trucks — that the group would ultimately ask the Port of Oakland to adopt.

By 2007, the port commissioners had become more familiar with the inner workings of the trucking industry, thanks in part to the efforts of community groups like WOEIP and the East Bay Alliance for a Sustainable Economy (the co-convener of Oakland’s Coalition for Clean & Safe Ports). During that same time, port commissioners were also becoming aware of inefficiencies within the port system and the economic and health consequences that high levels of diesel pollution were having on the community.

In 2008, the port adopted a goal of reducing health risks related to diesel pollution from its activities by 85 percent by 2020. It also took steps to reduce emissions, including switching from diesel to electric cranes and offering subsidies to help drivers upgrade their trucks.19 Still, the subsidies fell far short of the money needed for truck retrofits (typically between $15,000-$30,000 per truck, depending on the type of retrofit device20), and diesel pollution remained high. If the community wanted to see the 85 percent reduction goal become a reality, the port would need pushing.

After pulling together various health data, the Alameda County Public Health Department helped the task force craft aggressive strategies to improve the health of West Oakland residents and port drivers. They spent late nights poring over the details of the Maritime Air Quality Improvement Plan and, along with other members of the task force, identified hundreds of potential initiatives that could help reduce port emissions, weeded out the ones that weren’t feasible, and incorporated only the best into the plan.21

Together, a wide range of groups including West Oakland residents, environmental regulatory agencies, labor unions, community advocacy organizations, health agencies, and other stakeholders worked to build a movement to reduce air pollution at the Port of Oakland. The groups tackled the issue from many angles, conducting research, crafting policy proposals, and engaging in media advocacy to put community health in the spotlight and keep it there.

ACPHD also brought other voices into the mix. With public officials from the city of Oakland, ACPHD co-convened an interagency workgroup (a subcommittee of the task force) that included representatives from the Environmental Protection Agency, California Air Resources Board, and Bay Area Air Quality Management District. The groups met with one another’s boards to develop an organized message on multiple fronts, making sure to keep the health argument front and center. Together, they navigated a highly political process to press the port to adopt the best possible goals and the best mechanism for implementing them.

Media advocacy

Sandra Witt, then-deputy director of policy, planning, and health equity for the Alameda County Public Health Department, speaks about the connection between air pollution and local health at an asthma clinic staged in front of the Port of Oakland on February 10, 2009. Photo: Brooke Anderson.

The groups leaned on one another, leveraging their strengths to make political headway. One strategy involved getting the story in front of reporters and the public, which is exactly what the Coalition for Clean & Safe Ports and East Bay Alliance for a Sustainable Economy did in February of 2009. That month, EBASE released a report with the Pacific Institute that exposed the health consequences of Oakland’s port trucking system, which costs the community $153 million a year in medical expenses related to asthma, premature death, and increased risk of cancer and other diseases. The report, “Taking a Toll,” which was reviewed by allies including ACPHD, explained the breakdowns in Oakland’s port trucking system and prescribed solutions to help fix it. It also provided the perfect springboard for an attention-grabbing media event: an asthma clinic staged in front of port property.

Organizers at EBASE brought health professionals from the University of California, San Francisco, the Children’s Hospital & Research Center Oakland, the Alameda County Public Health Department and other groups to the clinic to provide free screenings to truck drivers and community residents and children. Hundreds turned out in support.22 Leaders from ACPHD spoke at the event, affirming the report’s alarming findings, and West Oakland residents and port drivers talked about the effects asthma has had on themselves and their families. The clinic drew media attention, with the story appearing in local papers23and radio producers inviting event organizers to speak on their shows.

Mixed results

In spite of strong evidence of both the economic and health-related consequences of port operations, the proposal to enact a Clean Truck Program encountered strong opposition from some members of the task force. Reducing diesel emissions would require overhauling the port trucking system and paying for pricey new equipment. With retrofits costing tens of thousands of dollars and new port trucks costing upwards of $100,000,24 low-wage truck drivers couldn’t be expected to pick up the tab. But, most port commissioners argued, neither could the port.

The state and the district both agreed to supplement Port of Oakland funds and pay a portion of the expenses. Still, those funds combined were not enough to make up for the shortfall. And while passing the expense on to shipping companies seemed like the best option given their large profit margins and the fact that cargo originates from these companies, the idea of making shipping companies pay raised concerns among some commissioners and staff that those companies might take their cargo elsewhere and forgo business deals with the Port of Oakland altogether. Advocates for the Clean Truck Program thought this was simply a scare tactic spread by the shipping companies.

By April 2009, the final Maritime Air Quality Improvement Plan that went before port commissioners had been grossly watered down. And although it still contained the ambitious goal of reducing diesel pollution-related health risks by 85 percent, it did not, according to several members of the task force, contain enough concrete actions or enforcement to help the port meet that goal. For example, it lacked a container fee to allow the port to collect funds from shippers to help drivers pay for new filters and other improvements to their trucks. Additionally, the plan did not include a Clean Truck Program, which the board instead decided to consider separately and on its own timeline.

Then-commissioner and Oakland resident Margaret Gordon, who helped convene the task force, called the plan a “skeleton”: “It’s not anything that has a lot of teeth in it because it’s still voluntary,” she said.

In the days leading up to the port’s vote, Dr. Tony Iton, then-director and health officer of the Alameda County Public Health Department, spoke before port commissioners to help illuminate the health context for their upcoming decision. And on April 7, the day of the vote, Oakland residents and community leaders came out in large numbers to express concerns about the shortcomings of the plan. Residents helped put a face on the real-world effects that excess diesel pollution was having on the community in the form of increased asthma rates and other health inequities, as well as related financial stress.

“This proposal … is not a long-term solution to the problem,” Chuck Mac, Secretary- Treasurer for the Teamsters Local 70 said. “At best, it’s short-term. If that’s what it is, the cost of the retrofits shouldn’t happen on the backs of truck drivers.”

Randall Bustamante, an English teacher at Oakland’s Mandela High, echoed that sentiment: “Too often, low-income means invisible, and I think this commission here can make a difference in making our people more visible and protected.” Bustamante advocated that the port pass a container fee so that truck drivers would not have to pay for their own filters, adding, “Every day that we wait is a day that more kids are affected, more lives are endangered, and more families are affected.”

In addition to supporting a container fee, Jack Broadbent, executive officer of the Bay Area Air Quality Management District, recommended the plan be revised to include a short-term measure to ban non-complaint trucks from entering the port.

“As currently proposed, the plan is too passive and too reliant on outside agencies enforcing state and federal regulations and providing subsidies to your tenants and customers,” Broadbent said.

The board ultimately approved the plan without modifications. Only one commissioner — Margaret Gordon — cast a no vote, citing the lack of enforceable measures as one of her main concerns.

Within days of the vote, Broadbent, Iton and the West Oakland Environmental Indicator Project’s Co-director Brian Beveridge co-authored an op-ed, criticizing the port for adopting a “toothless and noncommittal” plan that “devalu[es] the health of those who work at or live near the port and its major transportation routes.” The commentary, which appeared in the Oakland Tribune, called for a stronger and more sustainable plan requiring costs for reducing pollution be paid for “by the shipping industry and the retail sector whose products are being transported and not low-income truck drivers and community residents.”25

Since then, the Port of Oakland has made mixed progress in reducing its impact on the environment and public health. For example, to supplement the Maritime Air Quality Improvement Plan, which was passed without a Clean Truck Program, port commissioners later adopted a similar program** to reduce port truck emissions. However, unlike a full Clean Truck Program, the Port of Oakland’s version does not require a lease agreement between port trucking companies and the port. Nor does it set enforcement standards to ensure that trucking companies, not drivers, pay for state-mandated upgrades to port trucks.

Consequently, as a January 2010 retrofit deadline approached, although the port collaborated with state and district agencies to help fund expenses, their subsidies weren’t enough to fully cover costs. Individual drivers had to then pay the balance or leave the industry. And with even stricter requirements approaching in 2014, the port’s meager funding assistance has thus far provided only a stop-gap solution.

In spite of setbacks on the policy front, the stakeholder process did lead to other successes. It helped many Bay Area government agencies and other institutions form new relationships and strengthen existing ones. The Alameda County Public Health Department now has a presence on the Bay Area Air Quality Management District’s advisory committees. And ACPHD has improved an already robust relationship with the West Oakland Environmental Indicators Project, the group that originally invited the agency to join the port efforts, as well as other groups like the East Bay Alliance for a Sustainable Economy.

But perhaps the health department’s most important accomplishment that came out of the port stakeholder process was that it was able to take it on in the first place. Ten years ago, it would have been more difficult.

“We have spent years building our partnerships and internal capacity to tackle these challenging issues,” ACPHD Health Equity Coordinator Katherine Schaff said. “This allowed us not only to understand the port issues that residents were concerned about but also to know what our role should be in addressing them, and to have the capacity to do so.”

Developing the capacity to respond

Part of working for a public health agency means being pulled in many different directions at once. In the face of tight deadlines and funding constraints, it can be hard to see how all of a health department’s efforts connect, let alone be able to work on projects that fall outside of the more traditional realm of providing the community with health programs and services. That ACPHD was able to take a 30,000-foot view of operations at the port, connect it to health inequities in the community, and have the capacity to act happened because of a larger structural reorganization that began long before concerns about the port became widespread.

Beginning in the mid-1990s under the leadership of then-director Arnold Perkins, the health department began a process of trying to democratize the institution or, as Perkins has been known to say, “put the public back in public health.” His successor Tony Iton, who worked for ACPHD between 2003 and 2009 and served as its director from 2006 to 2009, described the health department before its reorganization as similar to an aircraft carrier, with the people it served being like “dinghies in the water.”

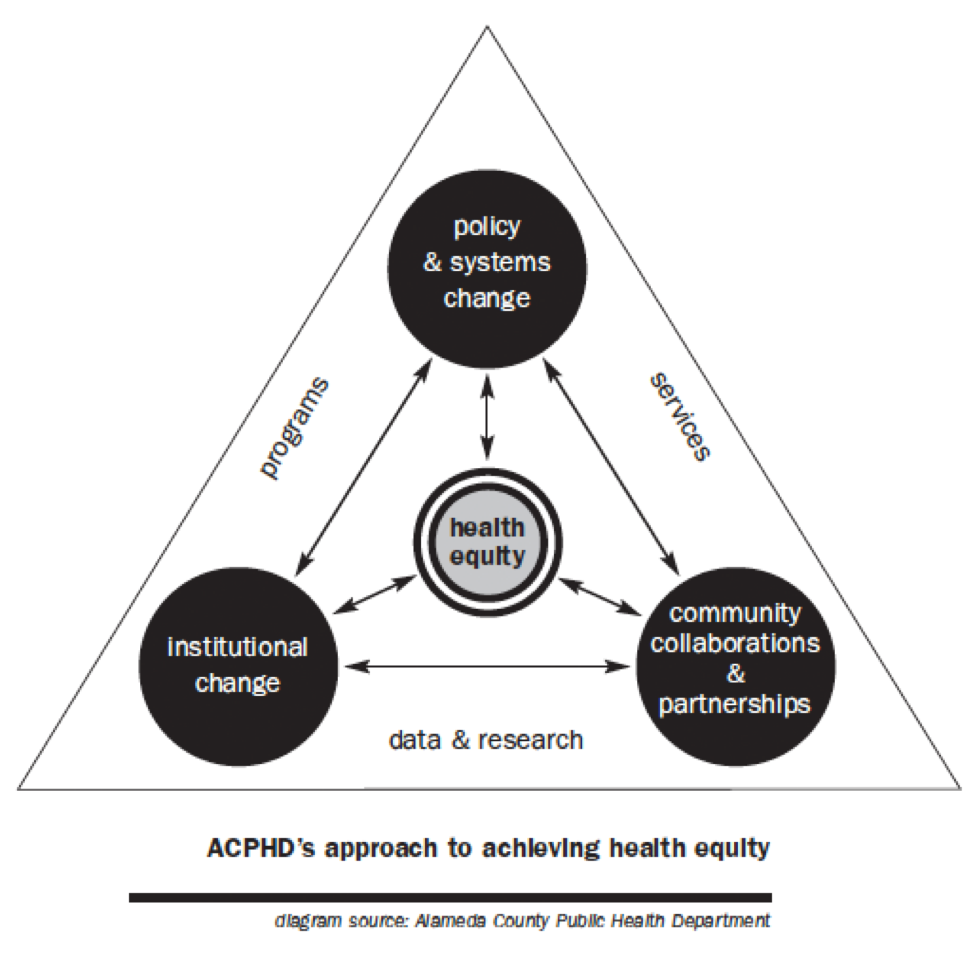

“It delivered services down but from a high perch,” Iton said. The department, he added, was too far removed from the community to really understand the root causes of health inequities. And so ACPHD began changing its form to drive changes in its function. First, it created regional offices that were closer to the communities it served, and it emphasized community capacity-building. ACPHD staff then started participating in neighborhood actions and reconceptualizing the nature of their work to include proactive efforts to prevent inequities rather merely respond to them after the fact. ACPHD staff now understand health equity as being part of the health department’s mission, and ACPHD has outlined a three-pronged approach to carrying out that mission, which in addition to community collaborations and partnerships, includes institutional change, and policy and systems change. And each of these areas includes programs, services, research and data.

Today, ACPHD is working to ensure its structural changes and robust focus on equity inform all of the department’s operations, from its training of new and existing staff to its delivery of health services. The health department works to create space for all employees to discuss health equity and its root causes and has five cross-departmental strategic planning workgroups that help employees leverage and expand their existing work in creative, equity-driven ways.

For example, as part of a public- and privately funded Place Matters initiative (affiliated with the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies’ national Place Matters initiative) that aims to promote health equity through policy changes in education, economics, criminal justice, land use, housing, and transportation policy, ACPHD staff are building and reinforcing the relationships they have with the community and non-traditional partners.

One of those partners is the Alameda County District Attorney’s Office. After discovering that a large number of children who are truant or chronically absent from West Oakland schools stay home because they have asthma, the co-coordinator of one of the health department’s Place Matters policy workgroups put the District Attorney in touch with ACPHD’s chronic disease director to collaborate on ways to reduce health-related absenteeism and keep youth out of the prison pipeline.

Together, they developed a plan: The District Attorney sends asthma-related truancy cases to the health department, and the health department enrolls them in the asthma program. As part of the program, asthma caseworkers take participants’ medical history and do a home inspection to look for environmental triggers for asthma, such as mold. They work with parents to remediate the triggers, which can mean supplying HEPA vacuums or providing mattress and pillow encasings. Caseworkers also help ensure that children are up-to-date on immunizations and prescriptions and conduct follow-ups to maintain progress. And if the health department finds that a child is struggling with other health problems, such as diabetes or mental health issues, it can put the family in touch with additional help. While this doesn’t address the larger issue of the connection between concentrated pollution and asthma, it does bring together multiple partners from different county systems to help improve young people’s health and keep them in school and out of court and jail.

ACPHD’s unique relationship with the District Attorney’s truancy program and Alameda County’s truancy court, as well as its two-year battle to reduce air pollution at the Port of Oakland, are just two examples of how the institution is using an emphasis on health equity to drive its daily work and open up new opportunities for action. And while ACPHD is quick to highlight the collaborative nature of its work, it also knows that part of its success comes from making sure the public is aware of that work. ACPHD has cultivated relationships with local journalists to make health equity a recurring topic in the news, and it announces its efforts through its own social media networks and website. After all, only with health inequities in full view can people see the need and urgency to eliminate them.

Lessons learned and implications for public health departments

The reorientation at ACPHD may sound like an organic and linear process, but it is, in fact, a major innovation that took place over the course of 15+ years and continues to evolve today. Yet that should not discourage other health departments from beginning or expanding existing efforts to improve health equity. Both ACPHD’s ongoing internal capacity-building and external advocacy efforts have taught its staff some valuable lessons that may be encouraging to others, no matter how seasoned or new they are to the issue:

Social change takes time

Tackling health inequities is a process. As ACPHD has shown, a structural reorganization can take decades, and even single equity efforts like the one to decrease diesel pollution at the Port of Oakland can take years. History shows us this is not unique to ACPHD. Some of the country’s greatest public health achievements have happened over the long haul. Take anti-tobacco advocacy, for example. It began more than 50 years ago and is continuing today. There has been great progress and major shifts in how the public and policymakers think about tobacco, but it is still the leading cause of preventable death in the United States. Knowing that significant social change takes time, health departments and other public health advocates can work to speed up that process by using community organizing and media advocacy.

Community residents and groups are essential partners

Few partners are as essential as the ones in a health department’s own backyard: community. The residents of a given region are often aware of threats to their health before those whose job it is to tackle those threats. Opening up a dialogue with community residents can help public health staff better identify both causes and solutions. And making sure community members have a voice is a critical part of developing their capacity to act — putting the public back in public health, as Arnold Perkins called it. There are limits to a government agency’s ability to advocate. Strong community partnerships built on power-sharing are essential to making real change. Additionally, while the health department can provide an official health lens as part of a media strategy, residents often offer the most compelling stories, which are critical to capturing media attention and influencing policymakers.

The health department should not expect to take the lead

As we saw with ACPHD’s participation in an interagency task force, when developing new and non-traditional partnerships, it is not always necessary or the best strategy for the health department to lead with its own agenda. Approaching collaboration with a willingness to listen and learn can provide the foundation needed to form lasting relationships. Once such partnerships are in place, stakeholders can then draw on one another’s strengths and fill in the gaps where there are weaknesses. These partnerships allow people outside of the public health realm to see how their work connects to health and helps the health department understand what role is appropriate for it in each unique context.

Acting on the social causes of poor health offers the best chance at lasting change

Traditional public health programs and services are important, especially in areas where health departments serve as a community’s medical provider of last resort. Still, addressing health harms after they happen leaves their causes untouched. Giving a child with asthma an inhaler and sending her back to a polluted environment may improve her breathing in the short term, but what about her future? What about the future of other children in the community, some of whom have yet to develop respiratory problems? The actions at the Port of Oakland and in Alameda County’s truancy court show that policy initiatives can be strengthened when health departments work with service providers, as those providers are directly connected to community needs and can add visibility both to the problem and to the policy solution that the health department is advocating.

Data are important but don’t speak for themselves

Knowing that an African-American child born in West Oakland can expect to die 15 years before a white child born in the Oakland Hills is alarming, but it alone may not compel people to act. Or it may inspire people to act but leave them ill equipped to know how. Health inequities in particular require acting at the systems level, and systems are slow to change. Even the Port of Oakland is just one institutional actor in a larger transportation system. As ACPHD saw, providing eye-opening statistics garnered the attention of individual port commissioners, but those commissioners are beholden to competing interests; they don’t make decisions in a silo. And data tend to focus on describing the problem rather than the solution. Thus, research is necessary but not sufficient to make change; it is just one tool in the toolkit. Remembering this up front can save a lot of frustration and keep staff motivated over the long term. It also underscores the importance of meaningful community partnerships that contribute to building community power.

The media have tremendous power to shape the public’s understanding of an issue

Changing a policy or transforming a system requires reaching the decision-makers who craft that policy or maintain that system. And this often means engaging the mechanism that influences the opinions of those decision-makers: the news media. This is exactly what organizers at EBASE did when they staged the asthma clinic in front of port property. The event put the port’s connections to health on reporters’ radars and led to local coverage online and on the air. To ensure comprehensive coverage, it helps to get to know local journalists over time, in advance of a media event. This allows reporters to develop trust with their sources and research complex issues in advance. Getting to know reporters can begin with something as simple as sending an email or taking a reporter out to lunch. The idea is to establish a line of connection and make yourself available as a source.

Implications for journalists

A healthy democracy hinges on the media’s ability to uncover information and share it with the masses. And uncovering that information involves journalists asking the right questions and finding the right sources for a story. When it comes to health, this is easier said than done. In the United States in particular, we put our trust in science and the medical system and look to it for answers to some of our most difficult health challenges. But even our medical system operates within a larger social, political and economic context. And illuminating that context is key to showing why some people get sicker and die sooner than others, regardless of their personal behaviors. Keeping the following ideas in mind during the reporting process can help journalists better unearth that context:

Sound reporting begins with asking “why?”

Much reporting on health identifies a problem and then stops there. But when it comes to health, there is almost always more to the story. So if a startling statistic comes across a reporter’s desk saying that children in West Oakland are hospitalized for asthma at a rate that’s three times higher than the county average, that reporter should ask why the health disparity exists in the first place. What environmental conditions might be triggering higher rates of asthma in West Oakland? What policies and practices have created those conditions? How is this affecting the community? Asking such questions will allow journalists to tell the richest, most complete story possible — one that includes the social context for health problems that may at first glance appear to be a simple matter of biology. That doesn’t mean other questions aren’t useful; they simply aren’t enough.

Connections to health are everywhere

Health doesn’t begin at the doctor’s office or in a university lab. Ties to health exist in unexpected areas: a community’s graduation rates, a family’s access to safe parks, the nation’s policies on transportation. So when a story on education or crime or public transit needs telling, ask how it relates to health.

Health departments are rich places to find sources

The broader context for health isn’t always obvious, even when we go looking for it. That’s why it’s useful to cultivate sources that have information on that context at the ready. Public health departments typically are linked to the communities they serve in multiple ways. As such, health departments may be able to connect reporters directly to community members with compelling stories, which can strengthen reporters’ writing and save time. But seeking out sources at the health department doesn’t mean being easy on them. Challenging the health department in news stories can help policymakers and health department leaders go further in their efforts to establish health equity.

Conclusion

People with power and privilege are more likely to be healthy than those without, even when they live just miles apart and call the same city their home. Increasingly, public health departments are digging deep to remedy this. That’s what the Alameda County Public Health Department started doing more than 15 years ago, and after uncovering some of the root causes of these preventable disparities — known as health inequities — ACPHD continues to restructure itself to improve the way it addresses them.

From taking part in a two-year stakeholder process to help reduce diesel pollution at one of the country’s busiest ports to working with a truancy program to reduce asthma-related school absences, ACPHD offers an encouraging example of how a health department can use an understanding of health equity to guide its daily work. These processes have been long, and successes haven’t come easy, but ACPHD is showing that the results are well worth it. Just as ACPHD continues working to incorporate health equity into all its efforts, other health departments can apply lessons to their own work on health equity. And journalists can play a role in helping them do so.

Timeline

Early 1900s: A California statute establishes that all tide and submerged lands, like that at the Port of Oakland, cannot be privately owned.i To this day, they are a part of the public trust, dedicated to common use.ii

1950s: After World War II, structural racism in areas like housing policy restricts homeownership opportunities for people of color and drives down property values, leading Oakland to experience “white flight,” with thousands of white property owners moving out of the city. This further exacerbates racial residential segregation and disparities in investments from one community to another.iii

1957: Based on the city of Oakland’s design, the California Department of Transportation builds the Cypress Street Viaduct. The two-tiered highway onramp cuts through West Oakland, displacing residents and businesses, isolating the region from downtown, and exposing the community — mostly low-income African-Americans — to increased levels of air pollution. iv

1980: Congress passes the Motor Carrier Act, which begins the process of deregulating the trucking industry. Union jobs evaporate and truck drivers lose pay and benefits, while becoming responsible for the purchase and maintenance of their trucks.v

1989: The Cypress Street Viaduct collapses during the Loma Prieta earthquake. vi

mid-1990s: The Alameda County Public Health Department (ACPHD) begins a structural reorganization, making its operations more community-oriented.vii

1998: After a protracted battle with the Bay Area transit agency Caltrans, West Oakland residents and activists succeed in getting the Cypress Street Viaduct rerouted around West Oakland. The new overpass is named Mandela Parkway.viii

1999: After a legal struggle and years of pressure from community members concerned about increased air pollution from the Port of Oakland’s growing operations, the port develops a plan to transform a portion of its property, long restricted for military use, into green space.ix The land is now known as Middle Harbor Shoreline Park.x

Early 2000s: West Oakland residents voice concern to community-based organizations about excess air pollution and respiratory conditions, including asthma, in their community.xi

June 2007: After receiving pressure from the West Oakland Environmental Indicators Project, Coalition for Clean & Safe Ports, and Ditching Dirty Diesel Collaborative, the Port of Oakland forms a task force charged with creating policies to reduce the port’s contribution to diesel emissions.xii ACPHD accepts an invitation to sit on the task force with other community and government stakeholders.xiii ACPHD and the city of Oakland then co-convene an interagency workgroup, a sub-committee of the task force that includes the Environmental Protection Agency, California Air Resources Board, and Bay Area Air Quality Management District.xiv

September 2007: The East Bay Alliance for a Sustainable Economy publishes “Taking the Low Road: How Independent Contracting at the Port of Oakland Endangers Public Health, Truck Drivers, & Economic Growth.”xv Produced for the Coalition for Clean & Safe Ports, it is the first report to discuss the state of the port trucking system as it relates to working conditions. The Alameda County Public Health Department takes a leadership role, with its then-director authoring the report introduction.

March 2008: After years of pressure from the Coalition for Clean and Safe Ports, the Los Angeles Harbor Commission approves a Clean Truck Program, which the Port of LA implements in October of that year. By 2011, the port has reduced its emissions from trucks by more than 80 percent.xvi

March 2008: The Port of Oakland adopts a goal of reducing the community’s health risks from port-related emissions by 85 percent by 2020.xvii

July 2008: The American Trucking Association files a lawsuit against the Clean Truck Program of the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, claiming that the program preempted federal deregulation laws. xviii,xix The lawsuit results in fear by the Port of Oakland to take similar actions.xx

August 2008: The Alameda County Public Health Department publishes “Life and Death from Unnatural Causes: Health and Social Inequity in Alameda County.” The report illustrates the social context for health inequities.xxi

February 2009: Community groups East Bay Alliance for a Sustainable Economy and the Pacific Institute release “Taking a Toll,” a report that details the health consequences of Oakland’s port trucking system.xxii

February 2009: The East Bay Alliance for a Sustainable Economy stages an asthma clinic and news conference in front of Port of Oakland property and invites port truck drivers and West Oakland residents to get tested. ACPHD provides asthma services and speaks at the event. Hundreds turn out in support, and the clinic captures media attention.xxiii

April 2009: Oakland’s port commissioners pass a Maritime Air Quality Improvement Plan.xxiv Members of the task force and community express concern that the plan is incomplete, does not adequately address labor issues, lacks a Clean Truck Program and contains no mechanisms for enforcement.xxv

June 2009: The Port of Oakland passes what it calls a Comprehensive Truck Management Program. The policy contains only one enforceable measure a ban to keep polluting trucks from servicing the port.xxvi The ban is the result of pressure from a state legislative hearing the previous month that compared the Port of Los Angeles’ Clean Truck Program to the Port of Oakland’s much weaker plan.xxvii

July 2009: The Port of Oakland passes a resolution calling for the federal government to adopt a National Goods Movement Policy, which would help fund and support the port’s efforts to reduce its negative social and environmental effects on the surrounding community.xxviii This indicates the port commissioners’ interest in getting direction from Congress around their authority to set standards in port trucking.

Issue 20 was written by Heather Gehlert. Special thanks to the many people who agreed to interviews, provided feedback on drafts, or otherwise contributed to this Issue: Matt Beyers, Alexandra Desautels, Teresa Drenick, Margaret Gordon, Tony Iton, Tamiko Johnson, Jennifer Lin, Jessica Luginbuhl, Brenda Rueda-Yamashita, Katherine Schaff, Kimi Watkins-Tartt, Sandra Witt, and Aditi Vaidya. Issue is edited by Lori Dorfman.

© 2012 Berkeley Media Studies Group, a project of the Public Health Institute

References

*Although an initial founder of the Coalition for Clean & Safe Ports, the West Oakland Environmental Indicators Project is no longer affiliated with CCSP.

**The Port of Oakland’s truck emissions reduction plan, dubbed a Comprehensive Truck Management Program, is available from www.portofoakland.com/pdf/CTMP_final_090616.pdf. Advocates for a Clean Truck Program say the plan’s designation as “comprehensive” is a misnomer.

1 Haugh, Christopher. Occupy Oakland’s Violent Turn Proves the Movement Has Lost Its Way. The Daily Beast. Retrieved February 8, 2012 from http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2012/01/30/occupy-oakland-s-violent-turn-proves-the-movement-has-lost-its-way.html.

2 Available from http://www.acphd.org/data-reports/reports-by-topic/social-and-health-equity/life-and-death-from-unnatural-causes.aspx. Last accessed September 10, 2012.

3 Iton, T. (2009, March 17). Presentation to the Port of Oakland’s Board of Commissioners. Oakland, Calif.

4 Case studies: Cypress Freeway Replacement Project. California Department of Transportation. Accessed February 9, 2012 from http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/environment/environmental_justice/case_studies/case5.cfm.

5 Case studies: Cypress Freeway Replacement Project.

6 Wilkinson, R., & Pickett, K. (2009). The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger. New York: Bloomsbury Press. pp. 85-87.

7 Available from http://www.acphd.org/data-reports/reports-by-topic/social-and-health-equity/life-and-death-from-unnatural-causes.aspx. Last accessed September 10, 2012.

8 Iton, T. (2009, March 17). Presentation to the Port of Oakland’s Board of Commissioners. Oakland, Calif.

9 Iton, T. (2009, March 17). Presentation to the Port of Oakland’s Board of Commissioners. Oakland, Calif.

10 East Bay Alliance for a Sustainable Economy. (2007, September). Taking the Low Road. How Independent Contracting at the Port of Oakland Endangers Public Health, Truck Drivers & Economic Growth.

11 East Bay Alliance for a Sustainable Economy. (2007, September). Taking the Low Road.

12 East Bay Alliance for a Sustainable Economy. (2007, September). Taking the Low Road.

13 East Bay Alliance for a Sustainable Economy. (2007, September). Taking the Low Road. p 11.

14 Smith, R., Bensman, D., and Marvy, P.A. (2010). The Big Rig: Poverty, Pollution and the Misclassification of Truck Drivers at America’s Ports. A survey and research report.

15 Smith, R., Bensman, D., and Marvy, P.A. (2010). The Big Rig.

16 East Bay Alliance for a Sustainable Economy. (2007, September). Taking the Low Road. p 8.

17 The Port of Los Angeles. Grants and Funding Opportunities: 2008 Port of Los Angeles Incentive Program. Retrieved October 12, 2012 from http://www.portoflosangeles.org/ctp/ctp_grants.asp.

18 Port of Los Angeles Inventory of Air Emissions2011. (2012, July). Starcrest Consulting Group, LLC. p. 181. Retrieved September 10, 2012 from www.portoflosangeles.org/pdf/2011_Air_Emissions_Inventory.pdf.

19 Kay, J. (2007, September 27). Big Rigs at Port of Oakland linked to health woes. SFGate.com. Retrieved January 16, 2012 from http://www.workingeastbay.org/article.php?id=422.

20 Interview with Aditi Vaidya, formerly of the East Bay Alliance for a Sustainable Economy. (2011, May 27).

21 Finalization in Sight for Maritime Air Quality Improvement Plan. (2009, August 7). Bay Area Monitor. Retrieved January 16, 2012 from http://www.bayareamonitor.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=107:finalization-in-sight-for-maritimeair-quality-improvement-plan&catid=53:augustseptember-2008&Itemid=89.

22 Hundreds Put Pressure on Port at Asthma Screening for Residents, Drivers. (2009). East Bay Alliance for a Sustainable Economy newsletter. Retrieved January 17, 2012 from http://www.workingeastbay.org/article.php?id=693.

23 Parker, M. (2009, March 24). The Polluting Port. San Francisco Bay Guardian Online. Retrieved March 27, 2012 from http://www.sfbg.com/2009/03/25/polluting-port.

24 Interview with Aditi Vaidya.

25 Iton, A., Beveridge, B., Broadbent, J. (2009, April 20). My Word: Port of Oakland commissioners need to show true leadership. Retrieved August 29, 2012 from www.acphd.org/media/148843/media_port_of_oakland_20090420.pdf.

References for timeline

i SPUR. (1999, November). The Public Trust Doctrine: San Francisco’s Waterfront. Retrieved July 24, 2012 from http://www.spur.org/publications/library/article/publictrustdoctrine11011999.

ii California State Lands Commission. (2007). The Public Trust Doctrine and the Modern Waterfront: Protecting the Environment and Promoting Water-Related Economic Development. Retrieved July 24, 2012 from www.slc.ca.gov/Misc_Pages/Public_Trust/Public_Trust.pdf.

iii Troutt, D.D. (1993). The Thin Red Line: How The Poor Still Pay More. Consumers Union of U.S., Inc. West Coast Regional Office. Available from http://www.consumersunion.org/aboutcu/publications.html.

iv Case Studies: Cypress Freeway Replacement Project, California Department of Transportation. (Site last updated 2011, August 29). U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration Office of Planning, Environment, & Realty. Retrieved July 24, 2012 from http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/environment/environmental_justice/case_studies/case5.cfm.

v East Bay Alliance for a Sustainable Economy. (2007, September). Taking the Low Road: Independent Contracting at the Port of Oakland Endangers Public Health, Truck Drivers & Economic Growth.

vi Earthquate Loma Prieta California 1989. National Institute of Standards and Technology. Retrieved July 24, 2012 from http://www.nist.gov/el/disasterstudies/earthquake/earthquake_lomaprieta_1989.cfm.

vii Interview with Tony Iton, former director and health officer of the Alameda County Public Health Department. (2012, January 5). viii Case Studies: Cypress Freeway Replacement Project, California Department of Transportation.

ix Interview with Aditi Vaidya, formerly of the East Bay Alliance for a Sustainable Economy. (2011, May 27).

x Middle Harbor Shoreline Park. Port of Oakland. Retrieved July 24, 2012 from http://www.portofoakland.com/communit/serv_midd.asp.

xi Interview with Margaret Gordon, former Port of Oakland commissioner and director of the West Oakland Environmental Indicators Project. (2011, June 21).

xii Interview with Aditi Vaidya. xiii Interview with Sandra Witt, former deputy directory of policy, planning, and health equity for the Alameda County Public Health Department. (2010, November 29).

xiv Interview with Sandra Witt. xxii Report available from http://www.pacinst.org/reports/taking_a_toll/taking_a_toll.pdf. Last accessed July 24, 2012. xxiii Interview with Aditi Vaidya.

xxiv Board of Port Commissioners, Port of Oakland. (2009, April). Maritime Air Quality Improvement Plan. Retrieved July 24, 2012 from http://www.portofoakland.com/pdf/maqip090515.pdf.

xxv Board of Port Commissioners Meeting. (2009, April 7). Audio of meeting retrieved July 24, 2012 from http://www.portofoakland.com/portnyou/cale_boar_01b.asp?Year=2009.

xxvi Port of Oakland. (2009, June 16). Maritime Comprehensive Truck Management Program: A MAQIP Program. Retrieved July 24, 2012 from www.portofoakland.com/pdf/CTMP_final_090616.pdf.

xxvii Interview with Aditi Vaidya. xxviii Resolution No. 09114: Resolution Adopting a National Goods Movement. (2009, July 7). Board of Port Commissioners. City of Oakland.