Get Healthy San Mateo County: How supporting community leadership can help address the root causes of poor health

Thursday, June 14, 2018About this case study

This case study is part of a series developed by the Berkeley Media Studies Group and supported by The California Endowment (TCE) that highlights the innovative work local health departments in California are doing to advance health equity. The San Mateo County Health System’s Health, Policy and Planning Program was one of three groups in the state recognized at “Advancing Health Equity Awards 2017: Highlighting Health Equity Practice in California Public Health Departments,” a ceremony and set of awards created by The California Endowment and administered by a planning committee representing leaders in the field, to elevate promising practices among local health departments. The awardees received grants of $25,000, with a grand prize of $100,000 going to the Monterey County Health Department. The awards and case studies, along with a suite of companion videos, were created to inform and inspire other health departments looking to engage in similar work.

To access the series on BMSG’s website, visit: https://www.bmsg.org/resources/publications/advancing-health-equity-awards-2017-highlighting-innovative-practice

To access the series on The California Endowment’s website, visit: http://www.calendow.org/wp-content/uploads/Health-Equity-Case-Studies-2018-web-optimized.pdf

To see the award-winning health departments in action, visit: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLLwLn83VLbvxIzuUc28CM2xLQ2GcdeUU1

Introduction

When school administrators approached Nicholas Walker, an 8th grade social studies teacher at Bowditch Middle School in Foster City, California, and asked him to help lead the school’s foray into restorative practices — an increasingly popular approach to discipline that helps reduce suspension and expulsion rates by involving students in the conflict-resolution process — he seized the opportunity.

“Kids tell me that they do better in my class,” Walker said. “I would like to think it’s as a result of restorative practices and the relationships that I built with them.” Under traditional disciplinary models, students who show signs of behavior problems often get sent to the office, which can lead to suspensions and expulsions, especially for students with disabilities and students of color, who tend to be disproportionately punished. According to federal data, students with disabilities are twice as likely to be suspended, and Black students are three times as likely to be suspended and expelled.1 Once they have been removed from school, these students are more likely to cross paths with the juvenile justice system.

Restorative practices help disrupt this pipeline by engaging both teachers and students in new methods for resolving disputes. Instead of immediately sending students to the office, teachers are trained to first try to handle conflict in the classroom. Often, they use a set of questions to guide small, impromptu conferences, where both the student who was harmed and the student who caused the harm come together to discuss any damage done and how they can repair it.

“Restorative practices rest on a fundamental hypothesis that people are happier and they’re more productive when people in positions of authority do things with them, rather than to them,” said Wini McMichael, wellness coordinator for the San Mateo-Foster City School District.

Through restorative practices, victims gain a voice — something that often gets stifled in the justice system — and all students involved gain empathy, emotional awareness, and a sense of connectedness, which makes it easier for them to share their thoughts, feelings, and concerns. Teachers and administrators also benefit, by hearing perspectives they may not have considered.

Through restorative practices, victims gain a voice — something that often gets stifled in the justice system — and all students involved gain empathy, emotional awareness, and a sense of connectedness, which makes it easier for them to share their thoughts, feelings, and concerns. Teachers and administrators also benefit, by hearing perspectives they may not have considered.

Additionally — and perhaps most critically — restorative practices have the potential to improve health.

“Research shows us that school connectedness is a very important factor that’s preventive,” McMichael said, explaining that students with high levels of connectedness are less likely to engage in risky behaviors like using drugs, less likely to have mental health issues, and more likely to excel academically. “They’re more likely to graduate; they’re more likely to show that they have strong academic achievement when they’re tested; and so, these things are going to lead to [a] better life and better health outcomes,” she added. This link between educational attainment and health is widely documented. The more education people have, the healthier they tend to be.

The work happening at Bowditch is one small but important part of a larger, health-promoting community collaborative called Get Healthy San Mateo County (GHSMC), led by the San Mateo County Health System’s Health, Policy and Planning Program (HPP). Through GHSMC, residents work alongside leaders from cities, schools, hospitals, and various county departments to make San Mateo County a healthy place for all community members to live, regardless of their income, race/ethnicity, age, ability, immigration status, sexual orientation, or gender. Education is one of the four GHSMC community-identified, high-priority areas for building healthy, equitable communities. “Restorative practices for us seemed like a very important opportunity to knit our educational attainment goals with our health goals more directly,” said Shireen Malekafzali, senior manager of Health, Policy and Planning.

Because the health-supporting potential of the work happening at Bowditch is so great, HPP is providing funding to expand the effort. The funds have allowed teachers, school psychologists, school counselors, and school mental health professionals to attend restorative practices trainings and use their newfound knowledge to train other teachers in the district. HPP has also expanded the work to partner with the County Office of Education to provide trainings and technical support across the 24 school districts in the county.

Additionally, HPP has helped Bowditch learn how to design surveys and collect data to determine whether its efforts are effective. While it is too soon to assess the project’s success at Bowditch, which is in its first year of using restorative practices in a comprehensive way, they are already noticing early signs of success, such as a reduction in student referrals to counseling.

“I’ve had zero mental health referrals this year, where last year I think I had anywhere from six to 10,” Walker said, adding, “[K]ids are more invested in the classroom too, so I think that it provides a little more intrinsic motivation to just do well in the class in general.”

For all its promise, the progress at Bowditch only scratches the surface of how HPP is collaborating with the surrounding community to support health through Get Healthy San Mateo County. Other efforts range from developing youth leaders to working with city officials to promote the consideration of health and equity in local policies and planning decisions. While these areas were once outside of public health’s purview, practitioners now increasingly view them as central to achieving health equity, or the ability of all people to reach their greatest health potential.

To better understand GHSMC and how it could serve as a model for other health departments, this case study examines why the collaborative is so important, breaks down how HPP is implementing it, and highlights challenges and lessons learned.

Uncovering hidden health inequities

Situated between San Francisco to the north and Silicon Valley to the south, San Mateo County is California’s third smallest county geographically; yet, it is home to more than 750,000 residents — a population size similar to the state of Vermont. With a dozen state beaches and seemingly endless parks and trails, San Mateo County boasts an impressive outdoor scene. The majestic Santa Cruz mountains run through the county, and several state conservation areas help to protect its wildlife and ocean ecosystems. The county is also a robust agricultural region, producing a variety of vegetables, such as brussel sprouts, leeks, and pumpkins, as well as other crops and commodities like wine grapes, flowers, and honey.

Long known for its natural beauty and agricultural bounty, San Mateo County became celebrated for something else in 2017: health. An annual report from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute ranked San Mateo the healthiest county in the state,2 based on life expectancy.3 That year, San Mateo County also ranked fifth for its residents’ quality of life and second, overall, based on a range of health factors including tobacco use, diet and exercise, education and employment rates, community safety, access to health care, and more.4,5

Long known for its natural beauty and agricultural bounty, San Mateo County became celebrated for something else in 2017: health. An annual report from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute ranked San Mateo the healthiest county in the state,2 based on life expectancy.3 That year, San Mateo County also ranked fifth for its residents’ quality of life and second, overall, based on a range of health factors including tobacco use, diet and exercise, education and employment rates, community safety, access to health care, and more.4,5

Health System staff are proud of these achievements, and the county has made significant progress in recent years; at the same time, Health System Chief Louise Rogers emphasized that they still have “a long way to go.”

Data reveal that the county has high rates of alcohol-related automobile crashes and a severe housing crisis; in fact, in 2017, the county was ranked 29th for the quality of its physical environment, which includes housing. It also struggles with health inequities related to race, ethnicity, and poverty.

With a large monolingual Spanish-speaking Latino population, as well as many Filipino, Chinese, and Pacific Islander residents, San Mateo County is a diverse community — one that has significant disparities between the “haves and the have-nots,” Rogers explained. “[W]e’re one of the most affluent communities in the nation, but the disparities here are really great,” she said.

For example, life expectancy for Black people in San Mateo County is almost seven years less than life expectancy for White people.6 Health inequities also show up in the county’s rates of obesity, diabetes, and asthma, which are growing throughout the county but are particularly high among low-income residents and some communities of color.

HPP’s Malekafzali describes these inequities as “unacceptable”; yet she also sees in them an opportunity: “In East Palo Alto, we have a school district [where] only 22 percent of students are meeting third-grade reading level, whereas Hillsboro, just a few miles away, they have 89 percent of their third-graders reading at [grade] level, which is a predictor of graduation rates.”

“So,” Malekafzali continued, “while the disparities are awful, what we should take from it is that we know how to get it right. If we know how to teach our students in Hillsboro, and [we know] what conditions need to be fostered to advance health, how do we take that and model it everywhere?”

Long and healthy lives for all: A community’s vision

There is no easy answer to Malekafzali’s question, no quick fix for eliminating disparities. Yet, regardless of how complex achieving health equity is, the San Mateo County Health System aims to do just that.

HPP’s vision is for all residents, regardless of their income, race or ethnicity, age, ability, gender, sexual orientation, or immigration status, to have equitable opportunities to be healthy and reach their full potential.

To reach that vision, the health department plans to leverage its strengths to address the root causes of poor health, Rogers said, mentioning Unnatural Causes: Is Inequality Making Us Sick?, a documentary series that laid bare the relationship between place and health and exposed the need to focus on the underlying social and environmental causes of health issues, rather than strictly medical interventions. Research shows that access to health care, while important, plays a relatively minor role in determining health, with only 10 percent of premature deaths being related to medical care.7

To reach that vision, the health department plans to leverage its strengths to address the root causes of poor health, Rogers said, mentioning Unnatural Causes: Is Inequality Making Us Sick?, a documentary series that laid bare the relationship between place and health and exposed the need to focus on the underlying social and environmental causes of health issues, rather than strictly medical interventions. Research shows that access to health care, while important, plays a relatively minor role in determining health, with only 10 percent of premature deaths being related to medical care.7

“We can [focus on medicine] all day long, and it’s just a mountain that we’ll never get to the top of,” Rogers said. Instead, she noted, health departments must tackle root causes through policy change and prevention.

That’s where Get Healthy San Mateo County comes in. The community collaborative, led by the Health System’s Health, Policy and Planning team, supports a variety of policy change and prevention efforts to advance health equity. GHSMC began in 2004 as a San Mateo County Board of Supervisors initiative that responded to the Surgeon General’s report on health disparities; the initial focus was on preventing childhood obesity, preventing alcohol, tobacco, and other drug use, and improving linguistic access to health care services for non-English speakers. As the San Mateo County Health System — and the field of public health more broadly — have expanded their understanding of root causes and health inequities, the initiative has evolved in ways that mirror those shifts.

The revised GHSMC also reflects an evolution in HPP’s strategic planning process, incorporating more robust community participation and engagement over the last couple of years. During the creation of the county’s 2015-2020 strategic plan, HPP worked with the community to develop a collective vision for what San Mateo County would look like if it fully supported health equity, not just through its intent but through daily practice.

The revised GHSMC also reflects an evolution in HPP’s strategic planning process, incorporating more robust community participation and engagement over the last couple of years. During the creation of the county’s 2015-2020 strategic plan, HPP worked with the community to develop a collective vision for what San Mateo County would look like if it fully supported health equity, not just through its intent but through daily practice.

HPP asked community members what areas they wanted the health department to spend its time on and what changes would make the biggest difference over the next five years. HPP then gathered feedback by holding workshops and focus groups, administering online surveys in five languages, partnering with community groups to distribute paper surveys, and conducting interviews with residents from low-income communities and communities of color — populations that are hard to reach though traditional methods.

Ten areas emerged as priorities, which the group then narrowed to four:

- stable and affordable housing,

- complete neighborhoods (those which create the conditions, such as healthy food options and transit access, that make it easier to be healthy),

- healthy schools, and

- economic development and financial opportunities for families.

HPP now directs its time, resources, and energy toward these four areas. Within those areas, HPP prioritizes the locations with the greatest health inequities in the county.

HPP looks at the four main issues in an integrated way. “A family doesn’t experience education alone or their jobs alone,” Malekafzali said. “They experience their whole family unit, whether they have opportunities for jobs, whether they can travel to school in a safe way, [whether] they can get to their jobs with transportation, [whether] they can put food on the table. So, because of that experience that families have, we decided we don’t have the luxury of just focusing on one or two things. We actually have to take a comprehensive approach that recognizes how families experience those inequities.”

From paper to practice: Implementing Get Healthy San Mateo County

HPP does a lot of outreach and engagement to break through public health jargon and make sure that the people it is working to serve understand the health impacts of the issues they are tackling and the resources that HPP has to advance equity and address root causes. For example, HPP recently developed a five-part video series focused on each of the four community-identified priorities and on the overall GHSMC collaborative. The series tells the story of how issues such as housing, jobs, and education are health issues and highlights opportunities to engage with nontraditional partners.

“Many people think about [health] from a very narrow viewpoint of medical services,” Malekafzali said, adding that HPP tries to illuminate “the social factors that determine their health outcomes, which are often the things at the forefront of their mind, but they are not tying it to the doctor’s visit they just went to.”

That’s not to say that HPP’s work is top-down — quite the opposite. Just as community members were involved in creating a vision for GHSMC, they play a critical role in executing it. In fact, next to health equity and prevention, collaboration is one of GHSMC’s values.

“Working together with key partners is one of our key approaches,” Rogers said. “We really don’t believe in taking the ideas off the shelf and then bringing them into the county.”

HPP partners include community leaders, city and county staff, elected officials, advocates, and regional partners. HPP actively reaches out to its various partners to offer support where goals are aligned. Additionally, HPP strives to put members of marginalized communities at the center of conversations about how best to improve health — something they do by working with community-organizing groups, implementing community planning efforts, and listening to community leaders, especially those representing low-income communities and communities of color.

HPP also has an open request for proposals every year, which allows them to learn directly from community leaders about the strategies and issues they are most interested in advancing and provide resources directly to support community leadership to implement their aspirations.

Malekafzali said HPP does this for both moral and practical reasons. “When we are in partnership with community, not only … do we better understand the issues, but we have access to better solutions and partnership with those community leaders to advance the solutions,” she said.

HPP approaches these partnerships with humility. “We really do recognize that community partners know their communities best, that we are not an all-knowing health department, that we have a lot to learn, and that even if our data shows one thing, a subpopulation could really share with us a perspective — a lived experience — that could look very different to that, and we are very open to learning,” Malekafzali said. “I think that perspective helps communities know that we are on equal footing together, that we are embracing them and lifting up their leadership, and that helps build trust.”

The nature of this collaboration varies depending on the project. Sometimes HPP funds a project but then steps back, leaving decision-making in the hands of the organization leading the change. At other times, they co-develop projects or co-lead them once they’ve been created. At still other times, they wear the participant hat. This could mean contributing data analysis to community projects; leveraging HPP’s health expertise and credibility as a trusted institution to deliver testimonies on public health issues; or helping to build relationships between health department staff and community leaders.

“HPP’s role is developed in partnership with community leaders to maximize impact and respect existing leadership,” Rogers said. “Trust and partnership with community is a critical aspect of making government effective, and HPP works hard to maintain it.”

Whatever the details, HPP’s role is most often a supporting one.

“When you are working on the social determinants of health, it often means you are working in arenas where health is not the leader,” Malekafzali explained. “You need to be in partnership with people who are the leaders in those arenas. … If we are in good partnership [with communities], they can identify ways in which we can support their power, we can support their agenda, and we can help simultaneously move the health equity agenda.”

What, then, does this look like in practice? HPP works with its partners to implement Get Healthy San Mateo County using six key, overlapping strategies:

Providing evidence-based policy tools

HPP regularly funds research and conducts descriptive studies that provide data to cities to inform their policymaking process and improve neighborhoods’ conditions to better support health. For example, when the city of San Mateo was considering wage policies, HPP partnered with them by studying low-wage workers to better understand who they were and how they would be impacted.

Prior to the analysis, many people assumed that low-wage workers were mostly high school students and other young people. But the data revealed that low-wage workers tended to be heads of households with children. HPP shared its research with the city council through study sessions and public materials, and it helped shape their understanding of the issue. Ultimately, the city passed a minimum wage ordinance — the first such policy in San Mateo County.

Engaging in city and community planning processes

Cities and community-led coalitions often invite HPP and the San Mateo County Health System to help them develop their ideas about how to improve health and to offer feedback on their planning processes, goals, or policies. Rather than engage in the coalition itself, health department staff serve as technical advisers. They add value to the coalition by bringing facts — and credibility — to the table, as well as health framing, which often helps people relate to an issue in a way that numbers alone might not.

Because San Mateo County has 21 cities/townships and an unincorporated jurisdiction, HPP focuses primarily on collaborating with the locations that have the highest health inequities. For example, HPP partnered with the city of East Palo Alto to bring best practices research and health equity expertise to their task force focused on identifying strategies to increase safe and healthy accessory dwelling units (often called granny or secondary units) without displacing existing tenants. HPP also supports community engagement in the process through a partnership with community leaders and the city.

Additionally, HPP partnered with community leaders and the County Planning Department to incorporate a health element into the North Fair Oaks Community Plan (similar to a general plan but for an unincorporated area); funded a legal aid group to provide technical analysis services for community members engaged in East Palo Alto’s general planning process; and delivered technical support to a coalition in South San Francisco engaged in bringing an equity voice to their downtown planning process.

Making research easily accessible to the public

HPP knows that its research is the most useful and has the greatest potential to influence health conversations and actions if people know about it. To that end, staff create toolkits and other publications to showcase their work and emerging best practices. HPP refers to this process as “democratizing data” and has created a data portal on the GHSMC website (see www. gethealthysmc.org/data) to make clear the inequities facing San Mateo County. The data include interactive maps and can be navigated by census tract, city or school district, as well as by topic. The website also houses a database of HPP’s partners and includes opportunities for action.

HPP is currently conducting two transportation equity-related analyses: 1) identifying “transit deserts” — locations and demographics with limited access to public transportation, and 2) identifying schools in high-need areas with large numbers of collisions preventing safe walking and biking opportunities. HPP has also partnered with school leaders to incorporate a new module into the county’s California Healthy Kids Survey that expands on the existing survey to include a more robust understanding of children’s health needs.

HPP is making this research available through presentations and one-on-one meetings with cities, schools, and community-based organizations, as well as through their website and in print.

Communicating and engaging with community

HPP conducts outreach through its monthly newsletter, Facebook and Twitter accounts, community events, meetings, and twice-yearly forums. For example, in January 2017, HPP co-hosted a forum with partners in the County Office of Education on the county’s racial gap in educational achievement to inform educators and administrators of the importance of proactive approaches to reducing racial disparities in education. HPP also held a forum on community benefits agreements (CBA) — contracts that hold developers accountable to communities by requiring them to provide a range of benefits to residents; in exchange, community coalitions agree not to oppose development. The forum featured a city official, a community organizer, and a legal expert to showcase the opportunity and limitations of CBA as a tool for building healthy, equitable communities.

HPP conducts outreach through its monthly newsletter, Facebook and Twitter accounts, community events, meetings, and twice-yearly forums. For example, in January 2017, HPP co-hosted a forum with partners in the County Office of Education on the county’s racial gap in educational achievement to inform educators and administrators of the importance of proactive approaches to reducing racial disparities in education. HPP also held a forum on community benefits agreements (CBA) — contracts that hold developers accountable to communities by requiring them to provide a range of benefits to residents; in exchange, community coalitions agree not to oppose development. The forum featured a city official, a community organizer, and a legal expert to showcase the opportunity and limitations of CBA as a tool for building healthy, equitable communities.

Events like these have led to requests from other partners for HPP to participate in efforts where health has not historically been represented. Now, public health language and data often appear in publications beyond those produced by HPP. For example, for the first time, the 2017 theme for San Mateo County’s annual housing-focused conference, Housing Leadership Day, was health and housing.

To continue educating the public and policymakers about health equity, HPP also brings health-related testimony and messaging to the table. “There are some people who are very persuaded by data, so we need to make that data available and accessible, and we as an organization have to be transparent in sharing it,” Health System Chief Rogers said. “One of our roles is to bring information to the fore. … But stories are also very, very powerful. Individual stories of how people’s lives can be changed for some people are more important than data. So, that’s another thing that we try to do is bring stories into the discussion.” For example, each video in HPP’s recently produced series on GHSMC features a story of a person’s or family’s experience with the issues facing the community.

Funding place-based prevention and health equity efforts

Each fall, HPP puts out an open call for proposals that will help advance health equity through one of the four community-identified priority areas. This ensures community leaders, who know their communities best, can propose solutions and receive resources to advance them. Each year HPP invests at least $150,000 in local nonprofits, community-organizing groups, and sister government agencies to carry out the work.

“We put our money where our mouth is, and we apportion a part of the program budget to funding our community partners. … In recognition of the community’s leadership, we bring funding to the table and say, ‘We will support you, your leadership, and the projects that you bring forth as critical to moving our health equity agenda [forward],'” Malekafzali said.

One of those proposals was from the San Mateo-Foster City School District expressing interest in bringing restorative practices and a train-the-trainer model to Bowditch and its other middle schools.

“We would not have been able to have this project at all if it hadn’t been for the support that we’ve had from the San Mateo County health department,” Wellness Coordinator Wini McMichael said.

HPP has conveyed the project’s early indicators of success — strong teacher participation and positive feedback from students, as well the potential to reduce suspensions and improve education levels — to the County Office of Education and has partnered with them to figure out how to bring restorative practices to each of the county’s 24 school districts.

“Now we are doubling down on that and bringing in some experts in the field to help us in partnership with County Office of Education, our partners on the ground, San Mateo-Foster City District, as well as some other school districts in the county that are implementing some of this work and saying, ‘Let’s all sit at the table, better understand what’s underway, and envision a future where restorative practices are implemented in all of our schools,'” Malekafzali said.

Providing technical assistance to support capacity-building

For HPP, this tactic is especially important in marginalized communities. To help build community power and make sure that the people who govern reflect the interests of the people they represent, HPP tracks vacancies on boards and commissions with an eye toward recruiting for those seats from within diverse communities.

“Often those most impacted by decisions are not in decision-making roles,” Malekafzali said. “Often times, decision-makers might hear about the stories of those that are being impacted by the issues but aren’t themselves impacted. So, having impacted community members at the table, not just advocating for themselves but actually as a decision-maker, is a critical step to achieving a just democracy and advancing health equity in our county and across the United States.”

A special focus on empowering and engaging youth

One of the clearest ways to see how HPP’s technical assistance and other strategies for implementing Get Healthy San Mateo County come to life is through its focus on young people. According to Rogers, both HPP and the wider San Mateo County Health System support early intervention strategies to help children grow up healthy, have jobs, stay in school, and stay out of the probation, behavioral health, and child welfare systems.

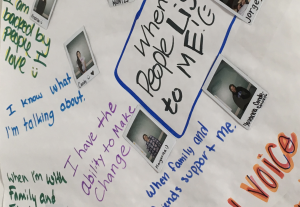

To that end, HPP has funded the Youth Leadership Institute (YLI), a youth-development organization, to engage young people in the county, especially those from underserved populations. YLI involves youth in community-based participatory research and helps them become advocates who feel empowered to share their stories and engage in the civic process. According to Fahad Qurashi, the Bay Area director of programs for YLI, 90 percent of the young people who participate in the organization identify as youth of color, and of those, more than two-thirds are on free or reduced lunch (an indicator of family income level).

To that end, HPP has funded the Youth Leadership Institute (YLI), a youth-development organization, to engage young people in the county, especially those from underserved populations. YLI involves youth in community-based participatory research and helps them become advocates who feel empowered to share their stories and engage in the civic process. According to Fahad Qurashi, the Bay Area director of programs for YLI, 90 percent of the young people who participate in the organization identify as youth of color, and of those, more than two-thirds are on free or reduced lunch (an indicator of family income level).

“In this community, we really need the leaders of the future to come from among these ranks, and we need them to be interested in running for elected office, and being members of the Board of Supervisors, and working in local departments, and, you know, being the head of the Health System and so on,” Rogers said. “So, it’s really exciting to see people — young people — engage in that possibility to realize that they can experience efficacy and to see it inspire them to go on.”

Youth who participate in YLI gain a range of skills from research to public speaking, which helps to prepare them academically for future careers and civically for community involvement. YLI also aims to make sure youth are informed about critical issues like power imbalances, oppression, and the historical context for health inequities — and to build their confidence in speaking out.

Through its work with YLI, HPP has been able to “engage those young people in some of the key policy decisions that ultimately really impact health,” Rogers said. “The youth have conducted surveys that helped us understand the problems more deeply. They’ve gotten together in large groups and in fishbowls to give adults greater exposure to their experience of the problems, and they’ve really been leaders in developing the solutions.”

One way youth can engage in decision-making processes is through involvement with the San Mateo County Youth Commission. Over the past couple of years, HPP has been contracting YLI to administer the commission, whose goal is to create a pipeline of leaders to support the county’s civic infrastructure and to make sure youth voices from all communities are represented.

Twenty-five youth between the ages of 13 and 20 sit on the Youth Commission and are appointed by the Board of Supervisors to advise on youth-related policy. The youth are then divided into five different committees: Adolescent Needs; Environmental Protection; Immigrant Youth; Legislative; and Teen Stress and Happiness. Here, too, the work often dovetails with that of HPP. The Adolescent Needs Committee, for example, produces a report on the mental and physical health of youth every four years using data that they analyze with HPP.

Twenty-five youth between the ages of 13 and 20 sit on the Youth Commission and are appointed by the Board of Supervisors to advise on youth-related policy. The youth are then divided into five different committees: Adolescent Needs; Environmental Protection; Immigrant Youth; Legislative; and Teen Stress and Happiness. Here, too, the work often dovetails with that of HPP. The Adolescent Needs Committee, for example, produces a report on the mental and physical health of youth every four years using data that they analyze with HPP.

The health department also asks youth to sit on other boards and commissions so that they are represented in places where decisions are made daily about the county’s strategies and resources — places where young people’s voices may not be heard otherwise. These include First Five Commission, Juvenile Justice Board, HIV Board, and Parks and LGBTQ boards, among others. So far, it’s working: According to Qurashi, about half of the Youth Commission’s members sit on other decision-making bodies in the county.

“They have firsthand experience as to how decisions are made at a county level, and they can actually shape and influence those decisions as well,” he said.

The Youth Commission recruits through YLI, as well as partnerships with HPP, schools, community leaders, and local organizations. One of the top priorities during the recruitment process is diversity. “We want a diverse commission that reflects San Mateo County,” Qurashi said. “So, that means ethnic diversity. That means district diversity. That means various levels of income being represented at the table, too, because that brings different perspectives.” It has not been too difficult to garner interest: In 2016, more than 50 young people applied for nine open positions.

“Having the youth in a place where they are providing input into the decisions that impact their future is important for good decision-making, and it’s empowering to youth,” Malekafzali said, noting that such leadership opportunities are an “important aspect of achieving health equity now and in the future.”

Qurashi said he also sees youth engagement as a civil rights issue: “It’s important that young people are not only informed of the decisions and efforts that are going to impact them and their lives, but they should be part of influencing what that looks like. … Often times, young people actually have the solutions; they’re just not given that platform or opportunity to provide [input].”

Qurashi explained that this is partly because adults tend to underestimate young people’s abilities. He described YLI as a way to eliminate stereotypes and tear down these walls between youth and adults. What’s more, involving youth can lead to faster progress.

“Young people can quickly catalyze a movement,” he said. For example, Qurashi noted that with recent YLI efforts to address payday lending, “young people actually were able to pass policy efforts that restricted payday lenders or predatory financial practices in vulnerable communities. They were able to do that in a matter of a year, while adult-led organizations and experts will struggle for five years to take a campaign like that forward.”

“Young people can quickly catalyze a movement,” he said. For example, Qurashi noted that with recent YLI efforts to address payday lending, “young people actually were able to pass policy efforts that restricted payday lenders or predatory financial practices in vulnerable communities. They were able to do that in a matter of a year, while adult-led organizations and experts will struggle for five years to take a campaign like that forward.”

Qurashi also emphasized that HPP is a major supporter of this work. Specific equity-focused projects that HPP and YLI have partnered on include campaigns to reduce sugar-sweetened beverages and prevent diabetes, as well as to increase access to public transportation.

“There’s a lot of expertise that they bring to the table, in terms of being able to navigate policy at a local level and knowing some of the players,” he said, adding, “There’s the relationships that they hold with certain departments and elected and community members, too, that we’ve leveraged for success. And they also hold their own expertise, too, when it comes to data collection, data methodology, and then kind of legitimizing the fact that there are health disparities and other types of inequities in San Mateo County.”

“It takes a lot to shift or change something when it comes to inequities,” Qurashi continued. But, he said, “the data paired with the youth power paired with the experts from the government — the Health, Policy, Planning team — gives us the best opportunity and chance to actually create that impact.”

Overcoming challenges

As with any work to reduce health inequities, the progress that may appear effortless from the outside often involves challenges along the way.

Before HPP could shift its focus to become more equity-centric, it first had to convince the Health System that it needed to begin working on issues, such as housing stability and economic opportunity, that are traditionally beyond the scope of public health departments. To make their case, HPP staff shared research showing that although an existing program to increase walkability had many benefits, it also came with unintended consequences: Improved walkability inadvertently raises housing costs and increases displacement, with major implications for health. This research, combined with insights from the community-engaged strategic planning process, was enough for HPP to gain Health System support. Once leadership was on board, HPP then began delivering presentations on the social determinants of health equity for other San Mateo County Health System divisions and programs, including Behavioral Health, Family Health Services, and primary care providers at the county medical center.

The emphasis on equity and prevention is shared throughout the entire San Mateo County Health System. “That is something that every part of our health system appreciates, even if they’re busy delivering primary care or regulating a restaurant,” Rogers said.

The Health System has also faced challenges because of its limited resources, which it must allocate carefully among the county’s 22 jurisdictions.

“We want to be prudent financial stewards so that we can extract every last dollar possible in order to do the good work that we want to do,” Rogers said.

Fortunately, health is proving to be a popular investment in San Mateo. “We’ve been pretty successful convincing leaders across the county who have to provide multiyear support that by investing in these strategies, over time, we really will see a difference,” Rogers said. “And so, we have cities that are making decisions in their local policy that really support health, and it’s pretty terrific to see.”

Still, HPP must walk a political tightrope at times. Rather than being able to overtly champion every promising health equity effort, staff remain politically neutral, often lending their support in non-controversial ways. HPP also coordinates closely with county leaders and runs ideas by them in advance.

Then, Rogers explained, there is the mental toughness that doing this work requires, with each new hurdle forcing staff to dig deep to maintain their motivation and momentum. “Getting people excited about addressing challenges that are fairly aspirational and may take many decades to accomplish is a great challenge,” she said.

Lessons learned

In the time since HPP began focusing more explicitly on health inequities, staff have gained many insights that may be useful for other local health departments:

Partnerships are essential. In San Mateo County’s case, collaboration includes community, city, and county partners. “It’s really about elevating the ideas that people have and bringing them forward, so I think that’s been a key attribute that’s led to the success that we’ve had so far in developing partnerships.” Rogers said.

Additionally, rather than stepping in toward the end of a project or process, HPP engages partners early and often, shows how their interests are aligned, and makes clear how they can contribute.

Respect the community’s expertise. Health System staff repeatedly emphasized the importance of supporting leaders in marginalized communities, noting that those experiencing health inequities should be at the center of efforts to eliminate them. Community-driven agendas are not only better informed, they are also more successful in persevering through obstacles if the work becomes controversial as local residents work to bring attention to their needs.

Build trust with community. HPP has accomplished this by being responsive to community needs. For example, instead of just distributing surveys and inviting community residents to health department events, HPP staff show up where the community is already gathering to demonstrate their shared interests and values. HPP regularly connects with community leaders and serves as a resource when called upon.

Make data widely available. Health departments can maximize their reach and impact by making their research as available and easy to understand as possible. HPP has done so by sharing reports and data through their website, newsletter, social media, and more. Providing easy access to data allows community groups to use and share the information in the ways that best suit their needs.

Take calculated risks. Although taking risks can lead to occasional setbacks, doing so is necessary to make progress. One type of risk HPP often takes — to great benefit — is investing in organizations that can support pilot projects. Such projects have allowed them to secure additional resources to advance their health equity work and has helped partners to better understand and embrace the need for changes at the policy and systems levels.

Approach all work through a health equity lens. HPP extends this philosophy to internal health department decisions, which can support or stymie external projects. Everything from creating a budget to hiring new personnel should be filtered through this lens. “The staff that we have is our largest resource in the health department,” Malekafzali said. “So, who are we hiring? What is their background? What’s their leaning around equity? Do they understand that? So, every single thing that you do should come through a lens of health equity.”

Get support from leadership. “In a government structure, hierarchy reigns still, and without your leadership support, it’s hard to get and build projects to scale,” Malekafzali said. “So, when you are building leadership support, think about the messages and messengers that resonate with them.”

Commit to the long haul. “Significant social change can take decades. [T]he only real way to make any headway on this is through a sustained effort over time,” Rogers said, adding, “It’s just not going to happen overnight.”

Vision for the future

Going forward, HPP and its partners aim to strengthen and expand their existing work. They recognize that even in a largely affluent community, health disparities exist, and they are striving to expand people’s understanding of health beyond the medical system and to support the policies and practices that promote health equity.

For the restorative practices happening in the San Mateo-Foster City School District, a next step will be increasing teacher participation, which is already nearing one-third of all teachers across the district’s four middle schools. Bowditch’s Walker would like to see the practice continue to spread to other schools in the district and elsewhere. Cities like San Francisco and Oakland have already incorporated restorative practices, and Walker hopes the momentum continues.

As for the Youth Commission, Qurashi said he wants youth commissioners to come together across California to have a statewide impact. Locally, he and colleague Adam Wilson, the commission’s program coordinator, would like to see the group continue to become a stronger and more diverse voice for policy change. Wilson said the Youth Commission is going to work harder to use their voice “to bring more policy recommendations to the Board of Supervisors, to city councils when possible, and to school boards as well.”

Supervisor Carol Groom, the County Board of Supervisor liaison to the Youth Commission, is a strong supporter of youth leadership. Looking into the future, Supervisor Groom stated, “San Mateo County values youth voices and the leadership of the Youth Commission to bring their perspective into county decision-making. I look forward to the policy opportunities the commissioners will advance over the next few years and hope to see some of our youth commissioners moving through the pipeline of leadership to hold elected office in the future.”

More generally, across health department efforts, Rogers said her vision is that “more and more people in this community have equal opportunity to [live] a healthy lifestyle.” She would also like to see more progress on RWJF’s indicators of health: “If you could go down that entire Robert Wood Johnson list of measures and indicators and see that they were more equally experienced, I think that would be amazing.”

To see video highlights of HPP’s work in action, visit https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4gQSa9TG9pw&feature=youtu.be.

Acknowledgments

This case study was written by Heather Gehlert. BMSG would like to thank Cookie Carosella for contributing reporting to this case study. We also thank the following reviewers for their insightful feedback: Jonathan Heller, Human Impact Partners; Shireen Malekafzali, San Mateo County Health System, Health, Policy and Planning Program; Wini McMichael, San Mateo-Foster City School District; Rachel Poulain, The California Endowment; Bob Prentice, former director (retired) of the Bay Area Regional Health Inequities Initiative (BARHII); and Fahad Qurashi, Youth Leadership Institute.

This case study was funded by The California Endowment.

© 2018 Berkeley Media Studies Group, a project of the Public Health Institute, and The California Endowment

References

1 U.S. Department of Education. School Climate and Discipline: Know the Data. Available at https:// www2.ed.gov/policy/gen/guid/school-discipline/data.html. Last accessed July 17, 2017.

2 Halstead, R. (2017, March 29). Marin Loses Its Ranking as Healthiest County in the State to San Mateo. Marin Independent Journal. Available at http://www.mercurynews.com/2017/03/29/marin-loses-its-ranking-as-healthiest-county-in-state-to-san-mateo/. Last accessed July 11, 2017.

3 California 2017 Health Outcomes, Overall Rank. County Health Rankings and Roadmaps. Available at http://www.countyhealthrankings.org/app/california/2017/rankings/outcomes/overall. Last accessed July 17, 2017.

4 2017 County Health Rankings Key Findings Report. County Health Rankings and Roadmaps. Available at http://www.countyhealthrankings.org/reports/2017-county-health-rankings-key-findings-report. Last accessed July 17, 2017.

5 California 2017 Health Outcomes, Overall Rank. County Health Rankings and Roadmaps. Available at http://www.countyhealthrankings.org/app/california/2017/rankings/outcomes/overall. Last accessed July 17, 2017.

6 Strategies for Building Healthy, Equitable Communities: Get Healthy San Mateo County, 2015-2020. Health Policy and Planning Division, San Mateo County Health System. Available at http://www.gethealthysmc.org/. Last accessed July 17, 2017.

7 Heiman H.J. and Artiga S. (2015, Nov. 4). Beyond Health Care: The Role of Social Determinants in Promoting Health and Health Equity. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Available at http://www.kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/beyond-health-care-the-role-of-social-determinants-in-promoting-health-and-health-equity/. Last accessed September 13, 2017.