Examining the public debate on school food nutrition guidelines: Findings and lessons learned from an analysis of news coverage and legislative debates

Thursday, December 22, 2016In 2010, President Barack Obama signed the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act (HHFKA), the first piece of legislation in more than 30 years to include substantial reforms to the United States Department of Agriculture's (USDA) school nutrition guidelines. In the five years since it passed, the new standards for the National School Lunch Program have been implemented in schools across the country. Some of the new guidelines include increasing offerings of whole grain-rich foods, increasing daily servings of fruits and vegetables, and offering only fat-free or low-fat milk. "Smart Snacks in School," another program implemented under HHFKA in 2014-15, requires that all foods sold at school during the school day outside the meal program — foods sold in vending machines, at fundraisers or events, which are known as "competitive foods" — also meet the same nutrition standards.

These programs are intended to provide nutritionally balanced meals and snacks to U.S. schoolchildren in an effort to address child hunger and promote good nutrition. Since these programs target low-income children across the country, the new nutritional standards could improve the health of the children most at risk for diabetes and other chronic health problems related to diet.

While Congress and the USDA are responsible for developing nutritional guidelines for school meals and competitive foods, implementation falls under state jurisdiction, and execution varies across the country. While many states have embraced the guidelines, others have undermined support for robust school nutrition policies, insisting they will impede individual liberties, fail to adequately feed children or result in massive food waste.

It is important to understand how debate about this precedent-setting policy has unfolded in either the news media or legislative spheres at the state and local level. Previous analysis of HHFKA in print and television news at the federal level showed a national conversation with many opportunities for advocates to improve their messaging.1 An understanding of how school nutrition has been framed in news coverage and policy debates at the state and local level since the passage of the HHFKA could provide valuable insights for advocates who are eager to see strong implementation in their schools. News coverage influences both how the public and policymakers perceive an issue and what they think should be done about it. Understanding the coverage is key for advocates working to build support around the country for policies that promote and maintain healthy school environments.

To that end, we examined state- and local-level debates about school food nutritional guidelines since implementation of the HHFKA in a divergent group of states. We explored questions like: What topics were discussed, who speaks about school nutrition guidelines in state- and local-level news and policy debates, and how do they talk about the issue? This study provides a look at how discussions of school food nutrition policies unfolded in the selected states in the wake of a landmark national policy.

What we did

To understand how advocates, schools, the food industry, policymakers and others have shaped discussions about school nutrition at the state and local level since the passage of the HHFKA, Berkeley Media Studies Group (BMSG) and the Public Health Advocacy Institute (PHAI) systematically examined news coverage and legislative and regulatory documents from 11 states. We analyzed how school meal and competitive food guidelines debates have been framed at the local and state level, who spoke about the guidelines and what they had to say, and how arguments and framing differed between states and between the news and legislative testimony.

With input from our advisory group, we selected 11 states representing a range of regions, demographic make-ups, political leanings and responses to the guidelines: Massachusetts, California, Illinois, Michigan, Iowa, Texas, Kansas, Oklahoma, Washington, Mississippi and West Virginia.

For the news analysis, BMSG searched the Nexis database for coverage that appeared from August 2012 to December 2015. This timeframe allowed us to capture the discourse from the first year of HHFKA's implementation through the most recent full calendar year. We collected news coverage from each state that referenced any school nutrition guidelines, whether HHFKA-related or those pertaining to separate state or local initiatives, and excluded newswires to ensure a greater focus on state and local news.

From the articles collected (n=2645), we randomly selected 20% to be coded. We developed a comprehensive coding instrument* to capture the range of ways state- and local-level news coverage about school meal and competitive food guidelines were discussed. Our coding instrument provided a framework for gathering information related to the type of article, policies mentioned, arguments for and/or against the guidelines, and speakers. Before coding the full sample, we used an iterative process and statistical test to refine the coding instrument and ensure that coders' agreement was not occurring by chance (Krippendorff's α ≥ .80 for all measured variables).2

For the legislative analysis, PHAI used Westlaw's State Regulatory Database and individual state legislative databases on state websites to locate proposed or adopted bills and administrative rules on school nutrition in the 11 selected states. Search queries included "school AND nutrition;" "school food;" "school AND snacks;" "sweets;" "obesity;" "overweight;" "beverage AND school;" "fundraiser AND school;" "school breakfast;" and "school lunch." PHAI's findings were triangulated with the University of Connecticut Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity Legislative Database.3 We collected the legislative history of each bill to see if any committee actions or votes were taken. Where there were committee assignments, we looked for any record of the committee's work on the bill using a Google search of bill number, state name and committee name. We looked for any regulatory history of proposed administrative rules through searches of each state's register for notices of hearings or opportunities for comment. Finally, we used Google searches of the proposed regulation number and name of the entity holding the hearing to locate any record of the hearing proceedings or comments made on the record. We date-limited the search to match the news coverage timeframe. Using a slightly modified version of the coding instrument developed for the news data, we coded each document located.

What we found: News analysis

Our initial random sample of news coverage yielded 534 articles. After eliminating articles that did not substantially discuss the school food nutritional guidelines, our final sample included 324 articles.

The vast majority of the articles were about nutritional guidelines for school meals (81%). Just over one in 10 articles discussed guidelines for both meals and competitive foods, and 7% mentioned only competitive foods.

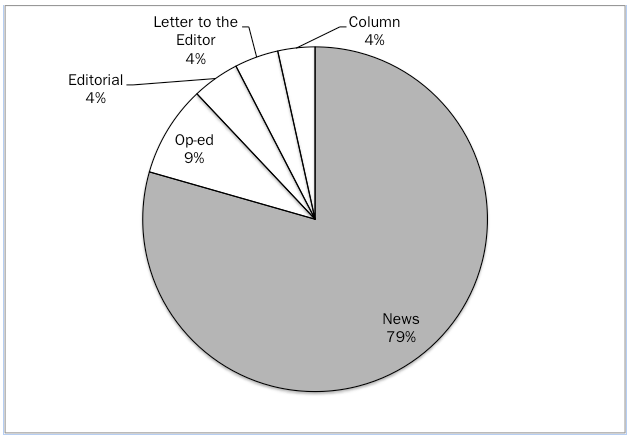

Most of the articles were straight news (80%); a few were opinion pieces, such as op-eds (9%), letters to the editor (4%), unsigned editorials (4%) or columns (3%). These figures stayed consistent when isolating for articles only about meals or snacks.

Chart 1: What types of articles appeared in news from selected states about school nutrition guidelines, 2012-2015? (n=316)

Why were stories about school nutrition guidelines in the news?

We wanted to know: When school nutrition guidelines were discussed in statewide news, why? Why that story, and why that day? Reporters commonly refer to the trigger for a story as a "news hook," so we identified the news hook for each article that addressed the question "Why was this article published today?"

Half of the articles were in the news because of a milestone in a state or local policy (49%), such as stories detailing a school district's implementation of the guidelines or its decision to drop out of the National School Lunch Program in response to the guidelines. Federal policy milestones were the second largest driver of news (26% of articles) and revolved largely around appropriations bills and exemptions. The remainder of articles were in the news because of a local event (10%), the release of a report (6%), an investigative report (4%) or because of a seasonal occasion (4%), such as the start of the school year. There were no major differences in types or frequency of news hooks for articles that covered meals versus those that covered competitive foods.

What were nutrition guidelines news stories about?

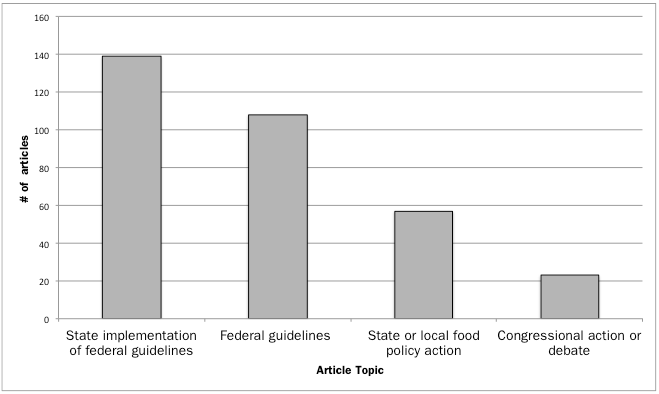

Chart 2: What were the topics in nutrition guidelines news stories from selected states, 2012-2015? (n=316)

Stories about school food nutrition guidelines were about the state's implementation of the federal guidelines (42% of articles) or provided commentary or updates about the federal guidelines (33%). The remaining quarter of articles had to do with a state or local school food policy not related to HHFKA, or instances of congressional action or debate about the federal guidelines (see Appendix for examples). The volume of news coverage varied substantially by state, with states with major media outlets (such as Massachusetts, California and Illinois) generally having more coverage.

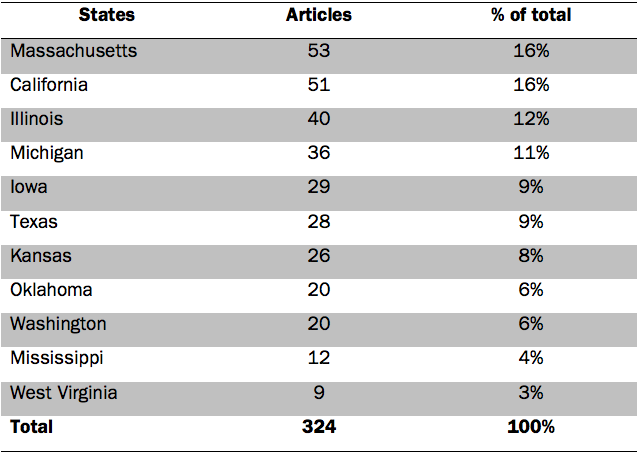

Table 1: How many articles originated from selected states, 2012-2015? (n=324)

Who spoke in coverage for or against the guidelines?

The most frequent speakers across the coverage were school nutrition staff members, who accounted for 19% of all statements. These were most often school nutrition staff sharing their experiences with implementing the guidelines. Pro- and anti-guideline arguments appeared with almost equal frequency from these speakers (53% anti versus 47% pro). Students were the second most frequent speaker in the news (10%) and were more likely to express sentiments against changes in the lunch menu (60% anti versus 40% pro).

Students were followed closely by federal elected officials, such as senators and members of Congress (9% of all arguments), who primarily spoke against the guidelines (73% of federal elected officials' arguments). Federal non-elected officials, such as Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack or USDA officials, were responsible for 8% of all arguments. Almost entirely appointees of the Obama administration, these speakers made arguments in support of the guidelines 94% of the time. State elected and non-elected officials rarely appeared in the news about school nutrition guidelines.

School administrators accounted for 6% of arguments about school food nutrition guidelines, and they were mainly critical of the guidelines, often citing the financial impact of the changes (65% anti arguments versus 34% pro arguments). Teachers appeared rarely in the coverage, but when they did they only spoke against school nutrition guidelines, most often echoing complaints from their students about the quality or quantity of the food.

What were the main arguments for and against the guidelines?

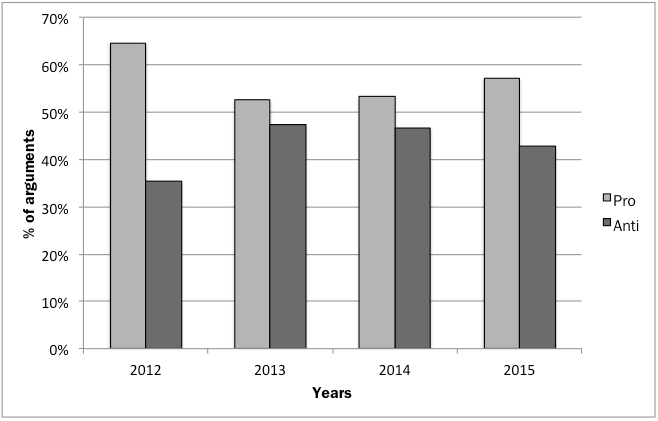

Overall, we found that most of the arguments (57%) made in state and local news coverage were in support of the guidelines. Articles written in 2012, when the HHFKA guidelines were first starting to be implemented, had a large majority of arguments in favor of the guidelines, a trend which diminished in 2013 and 2014, when the percentage of arguments for or against the guidelines were nearly even (53% pro versus 47% anti in 2013 and 2014). Arguments in favor of guidelines increased again slightly in 2015 (57% of arguments).

Chart 3: How did the amount of pro- and anti-arguments change in the news about school nutrition guidelines from selected states, 2012-2015? (n=1267)

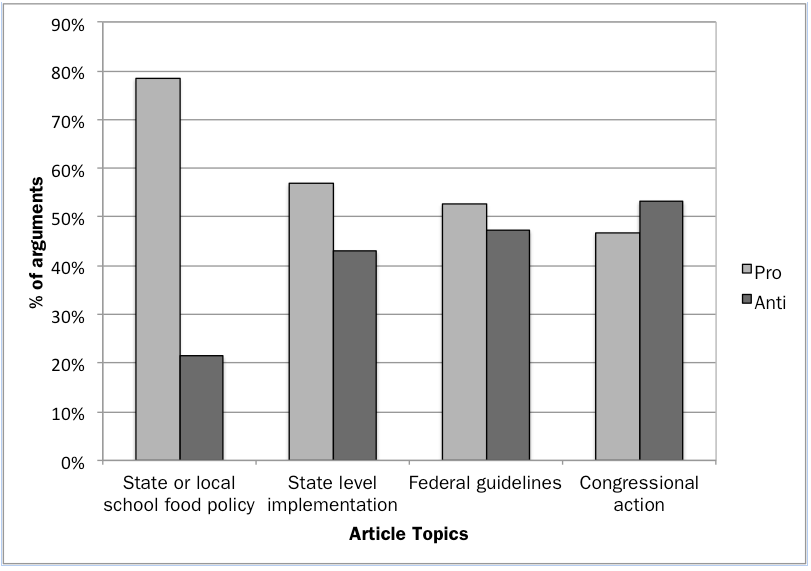

The level of support for school food nutritional guidelines varied widely depending on the topic of the article. Articles about state or local nutrition guidelines (not related to the HHFKA) received overwhelmingly positive news coverage (80% pro arguments). State level implementation of the federal HHFKA guidelines was generally positive, although by a narrower margin, and coverage of the federal guidelines, or Congressional action about them, generated the most critical news coverage.

Chart 4: Pro- and anti-arguments for school food nutrition guidelines in selected states by article topic, 2012-2015? (n=1267)

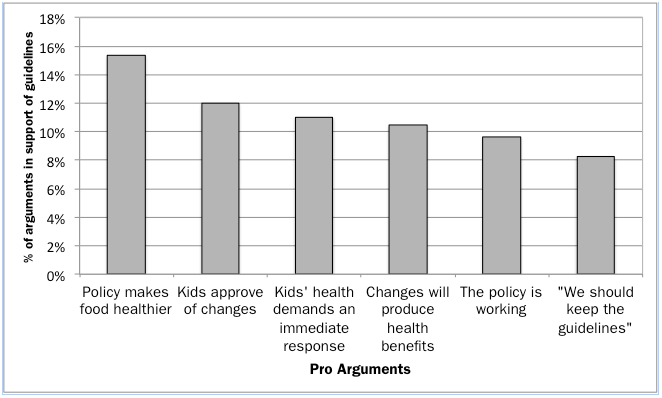

Speakers in favor of nutrition guidelines employed a wide array of arguments, with the most common being statements asserting that the new nutrition standards make food healthier (15% of pro-arguments). For example, Gayle Leader, food safety coordinator for Enid Public Schools in Oklahoma, told the Enid News and Eagle that following implementation of the federal guidelines, "the menu is a better balance than ever, and includes more fruits and vegetables, whole-grain foods, fewer calories and no saturated fats."4

The second most frequently cited argument in favor of the changes was that students approved of the changes (12% of pro-arguments), followed by assertions that the current state of childhood obesity across the country required a national response (11% of pro-arguments). Statements or allusions to the health or academic benefits of the new standards each encompassed less than 10% of arguments.

The top three pro arguments stayed the same when isolating for arguments made specifically about competitive foods. However, those speaking in favor of snacks standards used a smaller array of arguments, with the top three arguments — standards make food healthier, students approve of changes, and childhood obesity requires a national response — comprising 55% of all arguments made in favor of snacks regulation, compared to just 37% made overall. In addition, statements arguing that existing alternatives were unhealthy or "junk food" were more common in coverage of competitive foods than meals.

The states that had the most coverage with arguments in support of the overall guidelines were Oklahoma (69%), Michigan (68%), California (65%), Texas (64%) and Mississippi (64%).

Chart 5: What arguments for school food nutrition guidelines appeared in the news from selected states, 2012-2015? (n=723)

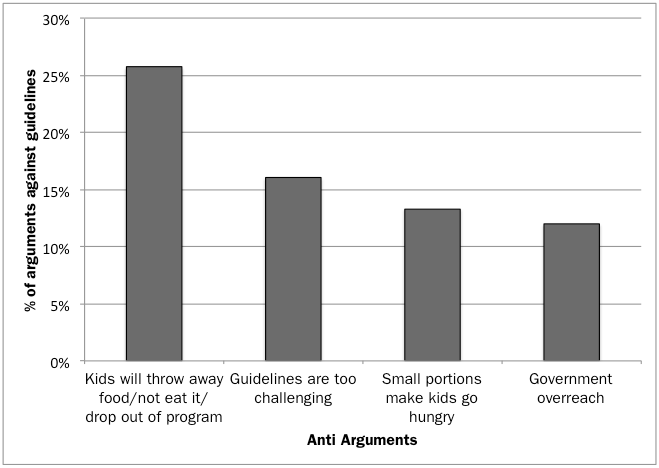

Just about half (47%) of arguments present in news coverage were critical of school food nutritional guidelines. In contrast to the large number of arguments used by advocates of nutrition guidelines, speakers who did not support new standards mostly framed their opposition in just a couple of ways. The most common argument was that students would not accept the new guidelines: that kids wouldn't eat the food; that food would therefore go to waste; or that students would drop out of the National School Lunch Program. These outcries were often attached to criticism of the HHFKA rule requiring students to take at least one serving each of fruits and vegetables with each meal. Said one Los Angeles Times editorial: "No one should have expected that putting more vegetables in front of elementary school students would instantly turn them into an army of broccoli fans. Plenty of food has been thrown out since the new federal rules took effect."5

Opponents also argued that the guidelines were too challenging to implement (16% of anti-arguments) and that the challenging standards constituted government overreach (12% of anti-arguments). No one exemplified this viewpoint better than Texas' Agriculture Commissioner Sid Miller, who infamously declared "cupcake amnesty" in response to restrictions on classroom celebrations like birthday parties — what he saw as the "big brother, big government control" exemplified by the guidelines.6

We found similar results when we isolated arguments specifically opposing nutritional guidelines for competitive foods, but there were a few differences. Although it was one of the most popular arguments made against school nutrition guidelines overall, the suggestion that small food portions would make kids go hungry was entirely absent from arguments made against snacks standards, perhaps because snacks are supplementary to a meal and not responsible for fullness. In addition, there were fewer concerns raised about the cost of implementing the new guidelines in articles about competitive foods than in articles about meals.

The states that had the most coverage with arguments opposing the guidelines were West Virginia (66%), Kansas (55%), Illinois (51%), Iowa (46%) and Washington (45%).

Chart 6: What arguments against school food nutrition guidelines appeared in the news from selected states, 2012-2015? (n=544)

Other features in the coverage

Mentions of disparities or health equity were present in only 8% of coverage. Discussion of equity included mentions of differences in food access, nutritional status, disease rates, and other health risks among different populations, communities and geographical locations. Racial disparities were never mentioned. When inequities did appear in the coverage they were most often in articles from California and were largely statements of fact. For example, a 2015 Los Angeles Times article recounts the results of a study that analyzed the health outcomes produced by two California laws that targeted competitive foods and beverages sold in schools: "The magnitude of the improvements depended on levels of school neighborhood socioeconomic advantage."7

In state news coverage, the National School Lunch Program was the most frequently mentioned (56%) policy or program, followed by the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act (38%) and Smart Snacks (9%). Other policies and programs mentioned occasionally in the coverage were the USDA's MyPlate Guidelines, Michelle Obama's "Let's Move" campaign and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP).

What we found: Legislative and regulatory analysis

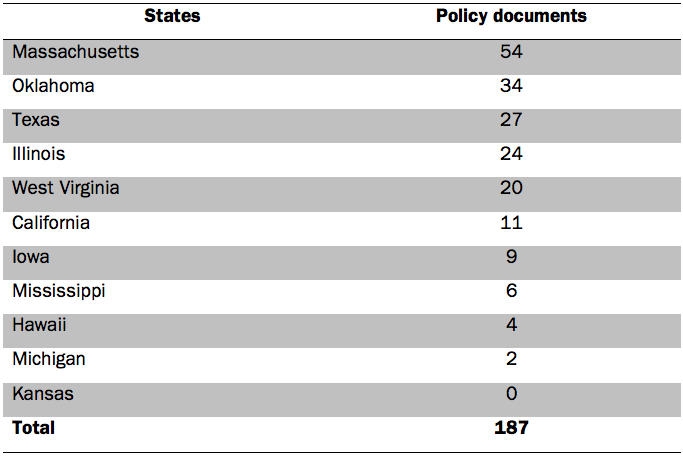

PHAI collected policy proposals consisting of potential laws or agency rules addressing school nutrition in the 11 selected states as well as any available related history, such as committee reports, hearings or public comments. Ultimately, 187 relevant documents were collected from the timeframe of this study: July 2012 — December 2015.

The most frequent document type we collected was regulatory testimony followed by legislative history (e.g., amendments or committee actions taken on proposed bills), proposed regulations, proposed legislation and final regulations. The state from which we found the most material was Massachusetts followed by Oklahoma, Texas, Illinois, West Virginia and California.

Table 2: How many policy documents originated from selected states, 2012-2015? (n=187)

About 38% of the materials we collected made no arguments either in favor of or against the school food nutritional standards stemming from the HHFKA. Such documents were usually the proposed bills or regulations themselves, which simply stated the proposed policy without providing a pro- or anti-guidelines rationale.

The purpose of 85% of these proposals concerned the Smart Snacks competitive foods policies. Almost all of these competitive food policy proposals involved implementation of the nutritional guidelines mandated by the HHFKA. Only 9% of the proposals we found addressed any aspects of the National School Lunch or National School Breakfast programs, which was the more dominant theme of news coverage.

One of the requirements of the HHFKA was that in the absence of a state policy providing Smart Snacks guideline exemptions for conducting fundraisers, there would be no exemptions permitted. The 2014-15 school year was the first in which the Smart Snacks rule would be in effect, and states scrambled to address this, which likely explains why it was the focus of 85% of school nutrition policymaking in these states during this period.

Of the documents that contained at least one policy argument (n=91), two-thirds argued in favor of the new guidelines. More than half of the arguments in favor of the guidelines argued that the guidelines will allow food service directors to provide healthier options or that the guidelines will benefit children's health. In every state except Oklahoma and Texas, there were more pro-guidelines arguments than anti-guidelines arguments presented. Half of arguments against the guidelines (n=34) raised implementation concerns and claimed that exemptions were required.

One significant difference in the arguments raised in the news coverage as compared to policymaking documents was that in states where news arguments were primarily anti-HHFKA guidelines, policymaking arguments were primarily pro-HHFKA guidelines and vice versa. This suggests that news debates do not necessarily reflect the tenor of the debate in the formal policymaking process.

The speakers in the documents addressing nutrition guidelines (n=91) included mostly school district staff (n=37) and few students, public health or health care practitioners, and food industry speakers (n=5 each). Surprising to us was the relative lack of speakers in testimony other than school district staff. It suggests that non-school staff stakeholders in child nutrition did not contribute as much to the dialogue around school food nutrition standards as one might have expected.

Conclusion

State and local news about the school nutrition guidelines largely focused on how the states were implementing the new federal standards. Articles about the guidelines were primarily straight news stories as opposed to opinion coverage, indicating that there may be a number of untapped opportunities for advocates to use opinion pages to shape the narrative around school food. The legislative and regulatory debate focused almost entirely on competitive foods, a sharp contrast with the news, which mainly covered meals.

Arguments in favor of the guidelines were prevalent over all years of news and legislative analysis; however, news coverage did shift in 2013 and 2014 toward being more critical of the guidelines. Part of this may have reflected difficulties with implementation, as well as backlash at the federal level. This finding warrants in-depth analysis and interviews with key stakeholders to fully elucidate the underlying causation.

State and local food policy actions received the most positive news coverage, with the federal guidelines drawing the most opposition. It's important for school nutrition advocates to be aware of this disparity, and it may be valuable to consider how to frame the issue in terms of state and local concerns, even when discussing the implications of federal guidelines and regulations.

School nutrition staff members were the most active speakers in the news about school food and in legislative and regulatory documents addressing nutrition guidelines, and were more likely than not to discuss the guidelines positively. In both news and legislative documents, school nutrition staff members primarily used the argument that guidelines would make food healthier. Students, federal elected officials, school administrators, and teachers were mostly critical of the nutrition guidelines in the news coverage we studied. School food advocates could consider targeting outreach to students, teachers or school administrators to garner their support and identify spokespeople who could speak in favor of the guidelines in the media. Teachers and principals, for example, could be very effective messengers to amplify arguments about the academic benefits of more nutritious school foods, an argument that appeared relatively infrequently in the news.

In addition, we found that aside from school nutrition staff, there were few speakers who advocated for nutrition guidelines in the legislative and regulatory debates we examined. This may represent an opportunity for greater participation in regulatory and legislative policymaking at the state level, through testimony, public comments and other means.

Health inequities were largely absent from news and legislative debates on school nutrition guidelines, only appearing in 7% of news articles and 2% of legislative documents. We did not find any mentions of race, even though we know that diet-related diseases disproportionately affect children and youth of color and lower-income children, and that school food environments are not uniform. By including information or appeals to values based in issues of equity, school food supporters could better make their case for why a health equity focus is needed in school nutrition policies.

*If you would like to view our coding instrument please contact us at info@bmsg.org.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant to Duke University from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation for the Healthy Eating Research program.

Special thanks to our advisory group, Jamie Chriqui, Jessica Donze Black and Colin Schwartz, for their insights and feedback in developing this analysis. Thank you to Lissy Friedman, JD, and Emily Nink for their research support.

å© 2016 Berkeley Media Studies Group, a project of the Public Health Institute

References

1. Wallack L, Winett, L. (2015). The Takeaway Series. Center for Public Health at Portland State University.

2. Krippendorff K. (2009). The Content Analysis Reader. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

3. Legislation database. (2016). University of Connecticut Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity. Available at: http://www.uconnruddcenter.org/legislation-database. Accessed December 16, 2016.

4. Zorn P. (2012). Healthier school lunches: More fruits, vegetables, whole grains added to menus. Enid News and Eagle.

5. Los Angeles Times editorial board. (2014, April 8). To curb school lunch waste, ease the fruit and vegetable rules. Available at: http://articles.latimes.com/2014/apr/08/opinion/la-ed-school-lunch-20140408. Last accessed December 16, 2016.

6. Brodesky J. (2015). Miller serves himself first, Texans last. San Antonio Express-News.

7. Brown W, Watanabe, T. (2015). Effect of junk food laws is uneven; Vampus restrictions helped students fight obesity in richer areas, but not in poorer ones, study finds. Los Angeles Times.

Appendix: Examples of news articles by topic area

State implementation of federal guidelines

Schools enjoy whole-wheat crust, by Jessica Lema

http://www.lincolncourier.com/x1803298041/Schools-enjoy-whole-wheat-crust

Healthier version of pizza to return to Wichita school menus, by Suzanne Perez Tobias

http://www.kansas.comews/article1118687.html

Federal guidelines

USDA loosens portions limits for school lunches, by Mackenzie Mays

http://www.wvgazettemail.com/News/201401070106

Snack rules help, even if they're hard to swallow, by Evan Halper

http://www.yakimaherald.com/opinion/editorials/snack-rules-help-even-if-they-re-hard-to-swallow/article_e661a170-1e2b-58da-888d-65bf848003bf.html

State or local food policy action

Healthy eating a decade in the making at Fraser schools, by Nick Mordowanec

http://www.candgnews.comews/healthy-eating-decade-making-fraser-schools-81165

Boston public schools working to upgrade the cafeteria, by Monica Disare

https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2015/07/29/boston-eyes-healthier-school-menus/tmJH2WVVBoO0Q0K4PplQ6O/story.html

Congressional action or debate

First lady decries school lunch moves, by Kathleen Hennessey

http://www.latimes.comation/la-na-flotus-school-lunches-20140528-story.html

Sen. Pat Roberts at the center of effort to reauthorize, and likely reform, school meal programs, by Justin Wingerter http://cjonline.comews/2015-07-12/sen-pat-roberts-center-effort-reauthorize-and-likely-reform-school-meal-programs