The child welfare system in U.S. news: What’s missing?

Tuesday, April 09, 2019Many of the United States’ most vulnerable children are served by the child welfare system, an integral part of how we care for children who have been hurt or neglected: In 2015, more than 3.3 million children were involved in a child protective services investigation or alternative intervention in response to reports of abuse.1 Communicating effectively about the child welfare system, a complex network of public and private agencies, nonprofits, and community-based organizations, can be challenging, especially if it means talking about socially or politically fraught issues like family dynamics or funding for public services.

When the child welfare system is strong, everyone benefits — not just children, but parents, families, and whole communities. One promising approach to strengthen the child welfare system is bridging the disconnect between child welfare and domestic violence services. These services have historically responded to victims separately,2 although many families who are involved in the child welfare system also experience domestic violence. In fact, in up to 60 percent of the families where domestic violence is identified, some form of co-occurring child abuse is also present,3 and, too often, that abuse has fatal consequences.4

In recent years, child welfare organizations and domestic violence programs have begun collaborating to better meet the needs of adults affected by domestic violence and children experiencing family violence. The Quality Improvement Center on Domestic Violence in Child Welfare, funded by the Children’s Bureau in the Administration for Children and Families at the Department of Health & Human Services, is leading a five-year project in sites around the country to determine best practices for how the child welfare system can better serve families experiencing domestic violence.

How can practitioners highlight those approaches and make the case for implementing them at the local, state, and national level? An important first step is to understand the current discourse about child welfare and how related issues like domestic violence appear. News coverage gives us a window into that discourse: The way issues are portrayed in the news affects how the public and policymakers understand them. If news coverage doesn’t illustrate the broader environments that surround specific incidents of child abuse or neglect, it may be harder for the public and policymakers to see the impact of environments and systems, including the child welfare system.

News coverage also sets the agenda for public policy debates.5-7 Journalists’ decisions about which issues to cover can raise the profile of a topic, whereas topics not covered by news media may remain outside public dialogue and policy debate.7, 8

In this study, we set out to understand the narrative about the child welfare system as it is reflected in the news. We wondered: how is the child welfare system portrayed in news coverage? Is it mentioned only when the system fails? Who is held responsible for resolving problems in the child welfare system? How, if at all, does domestic violence appear? How do issues of race and gender appear in coverage? And perhaps most importantly, what could patterns in the coverage mean for practitioners around the country working to build and maintain stronger child welfare protections that address the needs of families experiencing domestic violence?

What we did

We searched the Nexis database for news and opinion articles published in the top 50 circulating U.S. newspapers and The Associated Press between July 1, 2016 and June 30, 2017. Using Nexis’ subject tags, we searched for articles that only discussed the child welfare system and articles that discussed both child welfare and domestic violence.

We developed a coding instrument based on our review of the existing peer-reviewed literature, as well as our previous analyses of child abuse,9 childhood trauma,10 and domestic violence11, a in the news. We also incorporated themes that emerged from our preliminary analysis of a sample of articles published in “Child Welfare in the News,” a news digest disseminated by the Child Welfare Information Gateway.

After selecting a representative sample of articles, we evaluated each story to assess how the child welfare system is characterized, whether domestic violence is discussed, and how, if at all, connections between the two issues are illustrated. To better understand how the news frames issues of race and gender, we also coded images of people associated with the articles. We identified the role of the person who was pictured in the photos, as well as the race and gender of the photo subjects.

Before coding the full sample, we used an iterative process and a statistical test (Krippendorff’s alpha12) to ensure that coders’ agreement was not occurring by chance. We achieved an acceptable reliability measure of >0.8 for each variable.

What we found

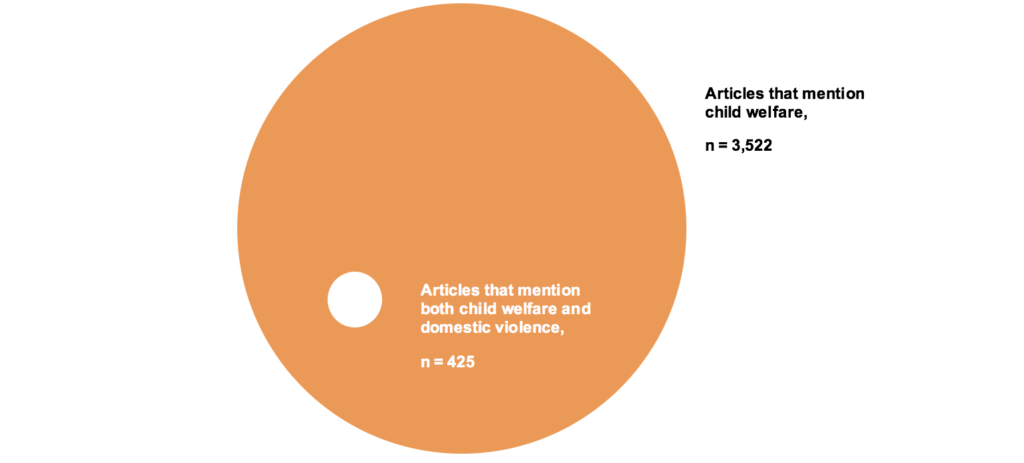

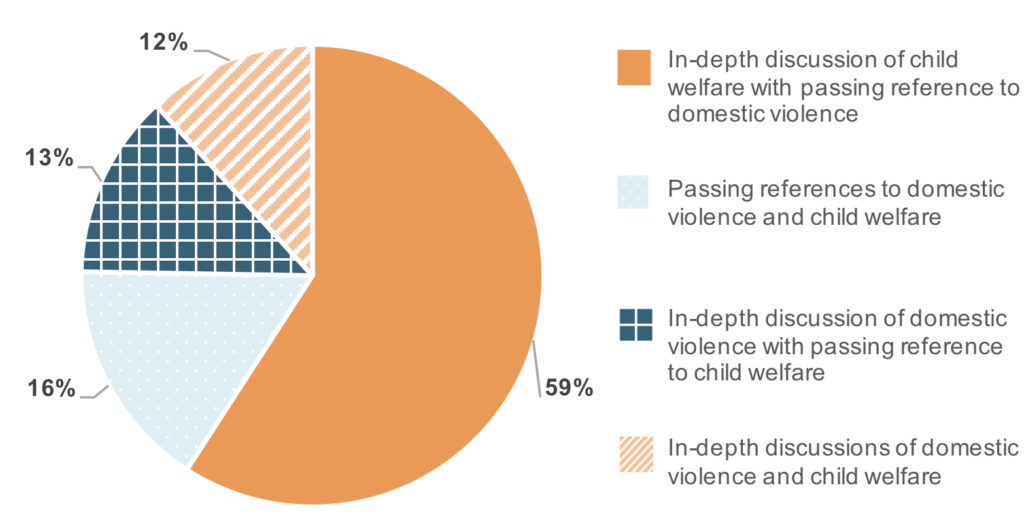

We found 3,522 articles that mentioned the child welfare system published in major U.S. newspapers and The Associated Press between July 1, 2016 and June 30, 2017 (Figure 1). Only 12% of these articles (n=425) mentioned both child welfare and domestic violence. We selected two representative samples — a random selection of 5% of articles that only referenced child welfare, and a random selection of half of the articles about both child welfare and domestic violence. We removed irrelevant articles (for example, stories that focused on child welfare issues in another country). Our final samples included 78 articles about child welfare only and 93 articles about both child welfare and domestic violence.

Figure 1. Only 12% of U.S. news from July 1, 2016 – June 30, 2017 about child welfare mentions domestic violence (n=522)

We first describe patterns in news articles about the child welfare system. We then review the unique features of the much smaller group of news articles that mentioned both child welfare issues and domestic violence, and analyze the photos that accompanied both types of articles.

The news about child welfare

Most stories about child welfare were news articles (83%). Opinion pieces (i.e., columns, editorials, op-eds, and letters to the editor) comprised 17% of the coverage.

Legislative and criminal justice events generated the majority of stories about child welfare in the news.

We wanted to know: When child welfare is covered in the news, why? Why that story, and why that day? Reporters commonly refer to the catalyst for a story as a “news hook.”

The most common news hooks in coverage about child welfare were related to policy or legislative actions to fund or reform the child welfare system (36%) or to horrific incidents of abuse or neglect that fell within the scope of the criminal justice system (35%).

Often, stories that were in the news because of a piece of legislation or a policy mentioned that the policy action was prompted by an incident of abuse. For example, The Associated Press reported on North Carolina lawmakers passing a measure that would require social workers to observe a child with his or her parent twice before recommending a return of physical custody, noting that this proposal followed the death of a toddler.13

Stories that were in the news because of criminal justice events were often about the trial or arrest of negligent or abusive caregivers (35%). An article in the Orlando Sentinel, for example, reported on the case of a mother who was being tried for the murder of her 18-month-old daughter.14

Other less common news hooks for articles about child welfare included community events (5%), the release of a study or report (5%), or features and investigative reports (4%). A few articles (3%) appeared in the news because of a seasonal milestone, like Mother’s Day or the 20-year anniversary of the release of the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) study.15, 16

News coverage about child welfare emphasized specific cases of abuse.

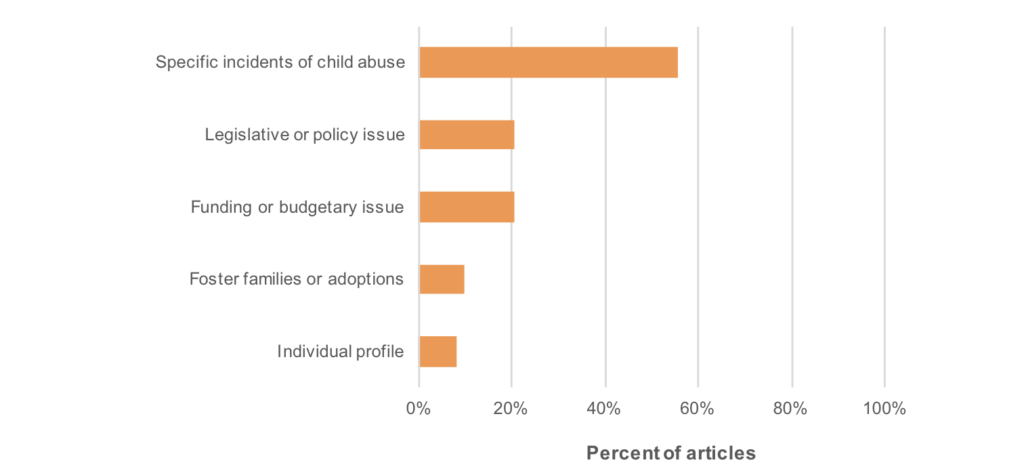

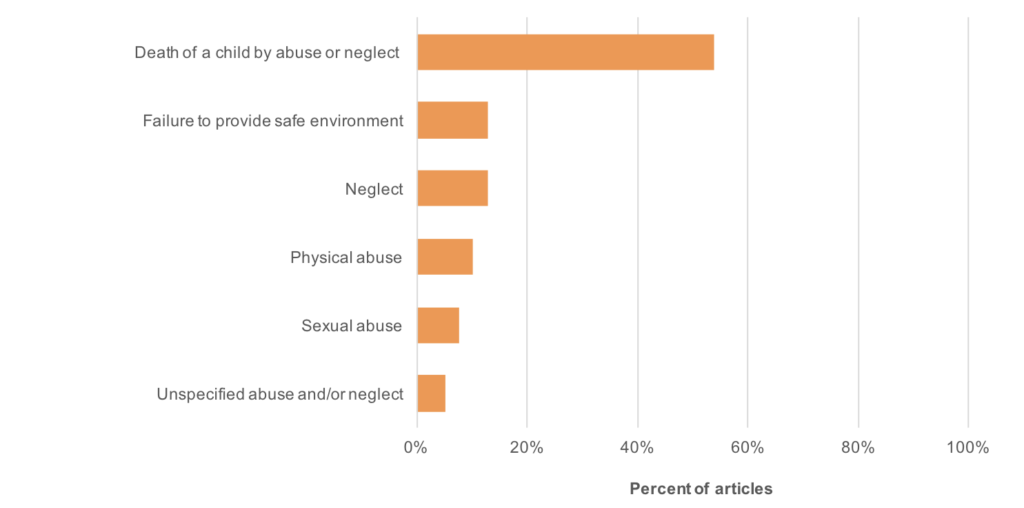

We also analyzed the topic of each article. Almost half of the articles described specific incidents of child abuse (49%; Figure 2). Articles that mentioned a specific incident of child abuse overwhelmingly focused on extreme cases: More than half involved the death of a child as a result of abuse (54%; Figure 3). Other types of abuse that appeared in the coverage included failure to provide a safe environment (e.g. because of adult drug use, 13%), neglect (13%), physical abuse (10%), and sexual abuse (8%).

More than half of the stories were about legislation or policies. These articles tended to focus on funding (27%) or reforming (26%) the child welfare system.

Stories about foster families and adoptions (10%) or those that profiled individuals involved with the child welfare system (8%) were less common (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Specific incidents of child abuse were the most common topic of U.S. news about the child welfare system, July 1, 2016 – July 30, 2017 (n=78)* * More than one topic could appear in each article.

* More than one topic could appear in each article.

Figure 3. The most common type of child abuse in U.S. news about the child welfare system was the death of a child, July 1, 2016 – June 30, 2017 (n=39)*

* More than one type of abuse could appear in articles about specific incidents of child abuse.

The most common speakers quoted in news stories were from the criminal justice sector, followed by child welfare.

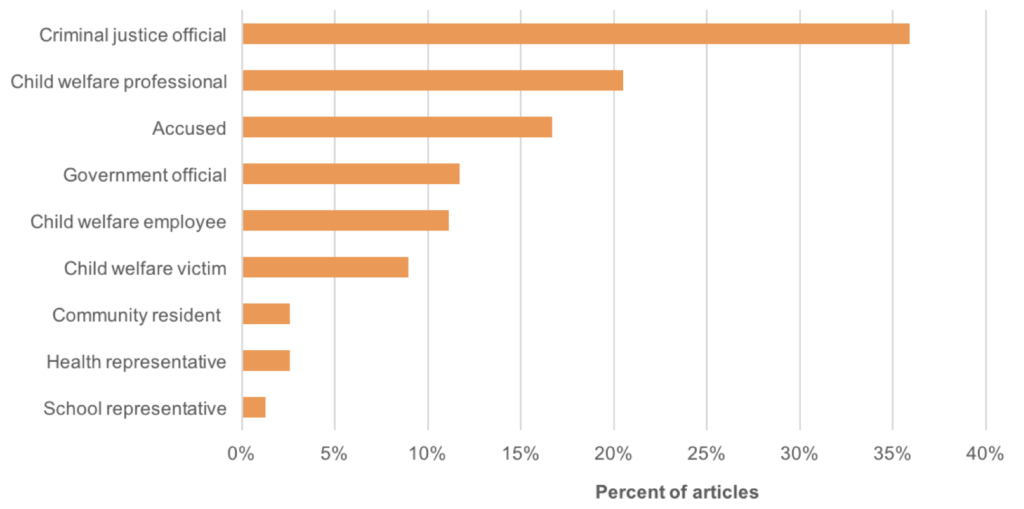

Given the news media’s focus on specific incidents of abuse, it is perhaps not surprising that the speakers quoted most often in stories about child welfare were criminal justice representatives. Police officers, detectives, judges, and others associated with law enforcement were quoted in 36% of articles (Figure 4).

Child welfare professionals (21%) and representatives of child welfare agencies (11%) appeared less frequently. Furthermore, speakers from important sectors like health care (3%) and schools (1%) were seldom quoted in the news about the child welfare system (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Criminal justice speakers dominated U.S. news about the child welfare system, July 1, 2016 – June 30, 2017 (n=78)

The news portrayed the child welfare system as struggling — if not failing.

We evaluated how each story was presented, or framed. For most issues, the majority of news stories are framed episodically — they tend to focus narrowly on a specific person or incident.17 Episodic stories are framed like portraits: They emphasize an individual’s role in causing or fixing problems with little to attention to the context of the problem depicted — or how to solve it.18

Stories that are framed more broadly, or thematically, appear less frequently in news coverage about any topic.17 Thematic stories are framed like landscapes, in that they might depict an individual or a specific case, but they also show some aspect of the broader context surrounding the person or incident.17 Thematic stories are important because when news consumers read, see, or hear them, they are more likely to name the role institutions, systems, and organizations play in solving the problem that is portrayed.17-19

Unlike many other issues,20-22 we found that more than half of the stories about child welfare were framed thematically, like landscapes (60%), as in a story from Kentucky that described how social workers made the case to legislators for funding the state’s social services agency in the midst of a heroin epidemic and a severe dearth of foster homes.23 Slightly over a third of thematic stories also mentioned specific incidents of abuse (37%). These articles either briefly mentioned that the systems-level issue was spurred by a specific incident of abuse, or they began with a portrait of a child who experienced abuse, then pulled back the lens to discuss environmental factors, systems, and structures. For example, a special report about drug use and parenting in the Fort Worth Star-Telegram opened with a detailed description of the drug-related death of Texas infant Zaveri Deponte before describing the overall prevalence of drug issues in the child welfare system:

Sadly, the circumstances surrounding Zaveri’s case are not unusual, experts say. “If you look at CPS cases alone, 75 to 80 percent of them involve drugs in some form or fashion,” said Dr. Jayme Coffman, medical director of the Cook Children’s Medical Center CARE Team.24

A photo of Semaj Crosby from a Chicago Sun-Times article about how the local child welfare agency failed to intervene in her abuse and death.23

The remaining stories in our sample (40%) were more narrowly drawn episodic or portrait stories that focused on specific incidents of abuse. For example, one episodic story described accusations against parents suspected of concealing the death of their child in the garage of an abandoned home,25 and elaborated the gruesome details of that incident, but did not go any further to talk about systems or structures.

When the news included a broader, landscape perspective, it tended to depict a broken or failing system. The majority of the stories with a thematic frame described failures or focused on critiques of the child welfare system (70% of thematic stories). A common criticism centered on the failure of agencies to remove children from abusive situations. For example, a scathing column in the Chicago Sun-Times criticized the local child welfare agency for the death of Semaj Crosby, who was killed despite multiple warning signs of abuse.26

We also saw articles that detailed the harm that children experienced while in the child welfare system or that implied that children were being removed from their homes and families unnecessarily. One in-depth article in The Arizona Republic, for example, profiled a one-year-old named Devani who was removed from her mother and suffered horrific abuse in foster care, despite her mother’s attempts to intervene.27

A photo of Michelle Calderon from a feature in The Arizona Republic about how a child welfare agency failed to care for her child, Devani, in their custody.24

When the news included explicit statements of blame for child welfare issues, child welfare agencies (44%) and their employees (9%) were often held responsible. It is, of course, vital to hold specific agencies accountable if they are found to have been negligent or failed to protect children. However, when news coverage focuses narrowly on the actions of child welfare agency employees, for example, without stories that also explore larger contextual issues like inadequate funding, the full picture of the system may be obscured.

In short, the news framing of the child welfare system illustrates the double bind agencies find themselves in — they are publicly faulted for taking action, as well as for failing to do so. Defenses of the system were infrequent: News coverage only occasionally mentioned the value of the system or included arguments for supporting it (21% of articles). When they appeared, defenses of the system were generally responding to prior criticism, as in an article about the New York City’s Administration for Children’s Services:

Mayor de Blasio defended the city’s troubled child welfare agency Monday during a lengthy, and at times testy, appearance before state lawmakers. De Blasio insisted the “overwhelming majority” of cases investigated by the Administration for Children’s Services are handled properly, and he blamed the media for painting an unflattering picture of the agency.28

Some articles characterized the system as overwhelmed and strained by a lack of resources for child welfare and the challenge of caring for the increasing number of at-risk children (27%). For example, one article in the Cincinnati Enquirer described the state of the child welfare system as “a world of tightening budgets and growing need … where the people assigned to watch over endangered kids see caseloads rise while their salaries rarely do.”29

When solutions to child welfare issues appeared in the news, the focus was on after-the-fact policy changes.

The news about child welfare was unusual in that solutions were referenced in more than half (55%) of articles in our sample. In general, the news about issues like crime, violence, and child sex abuse tends to focus on problems, rather than how to solve them.11, 30-32

Of the articles that discussed solutions, the strategies most often referenced were changes to child welfare agencies’ organizational policies (44%), such as limiting the caseload of child welfare workers or providing more employee trainings. These types of organizational changes were often proposed in response to controversies or tragedies, like the death of a child involved in the child welfare system. Coverage in the wake of these highly publicized cases often focused on punitive measures, such as firing or demoting employees or investigating a particular agency. In the high-profile case of Zymere Perkins,b a six-year-old boy who was beaten to death by his mother’s boyfriend in New York City, much of the news coverage focused on changes to the New York City Administration of Children’s Services, which included firing three employees and the resignation of the agency head.33

Other approaches to improving the child welfare system that appeared in the news included increased funding through legislation or budget measures (40%), such as an $11.8 billion budget proposal in New Hampshire Senate that supporters said would have addressed the state’s opioid crisis and the failing child protection system,34 or making changes to federal or state legislation (21%).

Coverage rarely discussed broader social conditions that have an impact on child abuse and family violence.

If the public and policymakers are to understand child welfare issues as social issues that we all have a stake in, it is important that the discourse include the factors outside of the child welfare system that give rise to family violence. However, social inequities and other structural or systemic causal factors for child abuse rarely appeared in the news (1%). Similarly, we scarcely saw any discussion of the role that other systems, like schools (<1%) or the criminal justice system (0%), could play in causing or addressing child welfare issues.

The news seldom focused on efforts by the child welfare system to address the underlying causes of child abuse or violence before it happens. A rare example came from New Mexico, where officials in Albuquerque and Bernalillo counties responded to the death of a child by allocating $3 million to increase prevention and treatment services for families facing mental illness, substance abuse, and incarceration.35

In summary:

The news about the child welfare system:

- frames the issue from a criminal justice perspective;

- highlights specific incidents of child abuse, particularly extreme cases that end in death;

- depicts a failing and overtaxed system; describes solutions — usually after-the-fact approaches to addressing past abuse;

- and obscures social inequities and other underlying factors that might result in child welfare issues.

The news about domestic violence and child welfare

If we want people to understand how domestic violence and child welfare affect families and communities, then the connections between the two issues need to be visible. Witnessing domestic violence is a form of childhood trauma,15 and in up to 60% of the families where domestic violence is identified, some form of co-occurring child abuse is also present.3, 4 However, by and large, news coverage rarely even mentioned the two issues in the same article, let alone illuminated the connections between them.

Domestic violence was mentioned in only 12% of stories about the child welfare system. Furthermore, most articles that mentioned domestic violence centered on child welfare and referenced domestic violence only in passing (59%; Figure 5). For instance, an article about the effect of the opioid epidemic on childhood trauma listed different types of adverse childhood experiences, including witnessing domestic violence, but did not discuss domestic violence any further.36

When domestic violence was a main topic of a story, the focus was often on co-occurring cases of domestic violence and child abuse. For example, one article reported on the arrest of a young man in Chicago who, while under investigation for a domestic battery incident against his partner, admitted to killing his baby.37

Figure 5. Substantive discussions of child welfare and domestic violence rarely appear together in U.S. news, July 1, 2016 – June 30, 2017 (n=93).

Articles that discussed domestic violence were more likely to be about specific incidents of maltreatment compared to articles that were only about the child welfare system (61% vs. 49%). Perhaps because of this focus on individual incidents, articles that discussed domestic violence were also slightly more likely to be in the news because of a crime (39% vs. 35%) and less likely to be in the news because of legislation or policy (17% vs. 36%).

Compared to articles solely about the child welfare system, criminal justice representatives were quoted slightly more frequently in articles that mentioned domestic violence (39% vs. 36%), as were child welfare employees (17% vs. 11%) and victims of child abuse (20% vs. 9%). Adult domestic violence victims spoke in 17% of articles that mentioned domestic violence, while domestic violence practitioners spoke in only 3% of those stories.

Child welfare stories that discussed domestic violence also tended to focus on more severe cases of abuse. Articles that mentioned both child welfare and domestic violence were slightly more likely to be about the death of a child by abuse or neglect compared to those that only discussed child welfare (58% vs. 54%). They were also more likely to contain graphic details about the crime(s) that had occurred (32% vs. 8%) and were also much more likely (41% vs. 15%) to mention drugs and alcohol, usually in reference to charges against the accused.

We wanted to know how coverage discussed strategies to address child welfare and domestic violence and whether it drew explicit connections between the two issues. We found that child welfare articles that mentioned domestic violence were less likely to mention solutions compared to articles that did not (41% vs. 55%). Furthermore, even articles that mentioned domestic violence rarely stated how it is related to child welfare: Only 14% of articles about both issues discussed domestic violence as a cause of child welfare issues.

When it appeared, the relationship between domestic violence and child welfare sometimes centered on criminalizing domestic violence victims: We found that 8% of articles about domestic violence and the child welfare system described victims of domestic violence facing child welfare-related criminal charges, which were often a result of their partner’s abuse of their children. A Chicago mother, for example, was beaten by her fiancé when she attempted to stop him from attacking her 3-year-old son. Her son was killed, and the article about the incident noted that she was being investigated for neglect in connection with the boy’s death.38 In another story, a woman was arrested and charged with child endangerment after officers, responding to reports that she was being attacked by her partner, found a loaded handgun in the home in reach of her two children.39

The coverage seldom described domestic violence as an issue within the purview of the child welfare system (6%). A rare example came from the New York Post, in an article about an investigation following the death of Zymere Perkins that included a review of “whether [child welfare] caseworkers are conducting domestic-violence screenings.”37 Another rare article that drew connections between domestic violence services and the child welfare system was a Miami Herald editorial, published after the death of a toddler in Florida, which argued that “calls to [the state’s abuse] hotline for incidents of domestic abuse between Ms. Dufrene and her husband should have kicked off a seamless intervention on behalf of [their children].”40

In summary:

Articles covering both domestic violence and child welfare:

- rarely appear;

- seldom address both issues substantively;

- are more likely to be about specific incidents of abuse and focus on graphic cases of violence involving drugs or alcohol;

- and do not describe connections between domestic violence and child welfare.

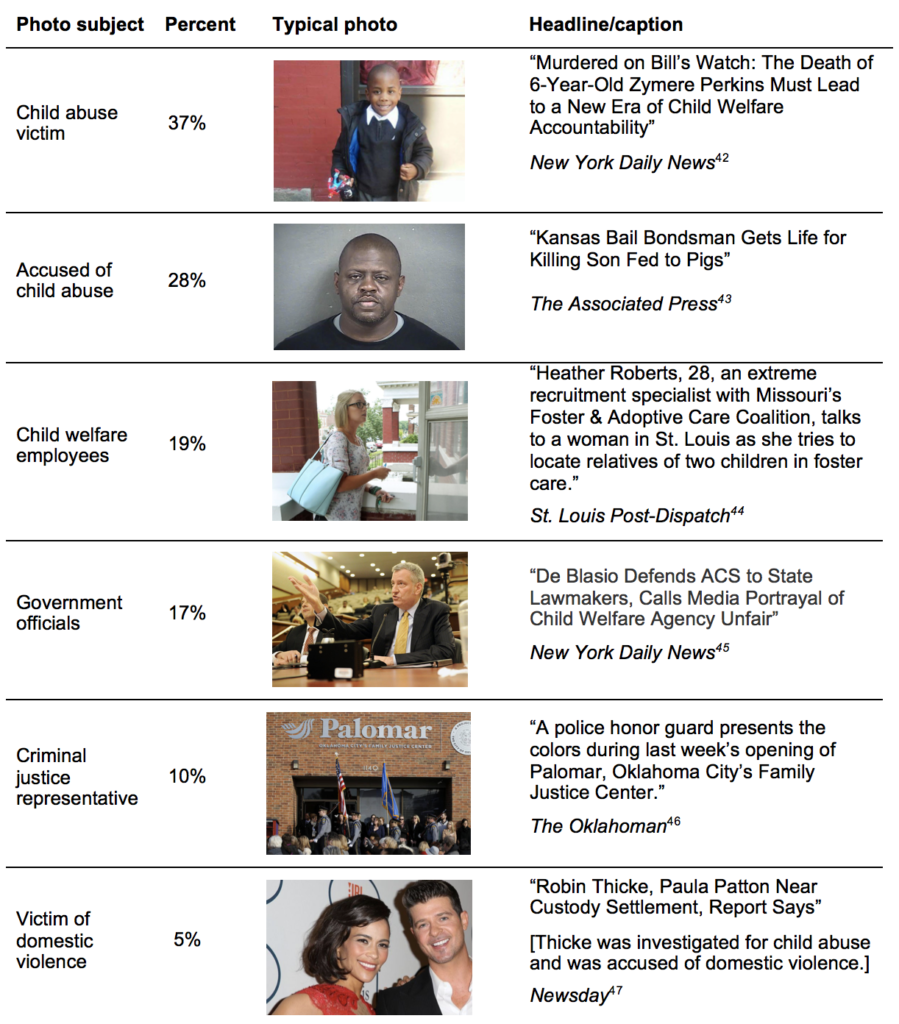

Picturing child abuse and domestic violence

We wanted to understand more about the people pictured in stories about child welfare and domestic violence. We wanted to know, who has a face, as well as a voice, in the news about the child welfare system? After removing photos that didn’t include people and photos unrelated either to child welfare or domestic violence, we had 102 photos of people to analyze associated with both article samples.

Though victims of child abuse and people accused of abuse were both less frequently quoted in the coverage than were other speakers (see Figure 4), they were the two most common subjects of photographs in the news: Child abuse victims are pictured in over a third of photos (37%) and those accused of child abuse in over a quarter (28%, Table 1). Nearly half of the images of victims and perpetrators of child abuse pictured people of color (47%), although very few articles (3%) mentioned race explicitly. Photos of victims of child abuse, in particular, featured mostly children of color (66%), mirroring the fact that children of color are overrepresented in the child welfare system.41

We also found that the majority (60%) of people accused of child abuse in photos were men, and most of those (60%) were men of color. Though women appeared less frequently as perpetrators of child abuse, most (83%) who did appear were white. Only 5% of photographs pictured images of domestic violence victims, all of whom were women (Table 1).

Child welfare employees (19%) and government officials (17%) were less often photo subjects in news about child welfare (Table 1). Only 10% of photos featured criminal justice representatives. However, most photographs of people accused of abuse were set in a jail or a courtroom, visually reinforcing the role of the criminal justice system in child welfare and domestic violence issues. All of the government officials pictured were white, as were the vast majority of child welfare employees (68%) and criminal justice representatives (70%).

In summary:

Photographs associated with news about child welfare or child welfare and domestic violence:

- are dominated by victims of child abuse and people accused of abuse;

- and often featured children of color as victims of child abuse, while government officials, child welfare employees, and criminal justice representatives were mainly white.

Table 1. Photos in U.S. news coverage about child welfare showed mostly child victims and people accused of abuse, July 1, 2016 – July 30, 2017, (n=102).

Conclusion

News about the child welfare system was driven by tragic stories of individual cases of harm and death, painting a picture of a system that is failing, inadequate, or, at best, overwhelmed. When solutions to issues in the child welfare system were discussed, the focus was on punitive, after-the-fact measures in response to high-profile incidents. That’s important because how the news depicts problems can shape how audiences understand solutions and why they matter. If preventive or community-based solutions are missing from the coverage, it could make it harder for policymakers and the public to imagine tangible change in how the system serves the country’s most vulnerable families.

There was little discussion of health equity or racial justice in news coverage about child welfare, despite the fact that children from African American and Native communities are overrepresented in the child welfare system.1, 41 On the other hand, most of the photographs of families involved in the child welfare system portrayed people of color. The prevalence of these photos, with the absence of additional information about systemic inequities, could easily reinforce harmful stereotypes about families of color.

Despite overwhelming evidence about the overlap between child welfare and domestic violence, the connections between them were seldom visible in the news: Few stories even referenced the two issues together; those that did focused narrowly on specific incidents of graphic violence. The absence of explicit connections between domestic violence and child welfare in the news could obscure the significant overlap between the two issues and make it harder to make the case for an integrated response at the local, state, and federal levels.

Our study exposes limitations and gaps in the public narrative around the child welfare system — a critical piece of how we care for our nation’s most vulnerable families. These findings suggest avenues for improving how we communicate about the child welfare system, its intersections with domestic violence, and why improving the system benefits whole communities. With an eye toward filling these gaps in the public discourse and building on its strengths, we make recommendations for practitioners and journalists to aid them in telling a more complete and accurate story about how families experience both domestic violence and child abuse.

Recommendations for practitioners

It is vital for reporters to continue to hold the child welfare system to account when it falters. But the child welfare system does not stand alone — many forces contribute to the health and well-being of children. Focusing solely on tragedy and failures could obscure the role of other sectors in supporting children and their families and make family violence feel inevitable. A more complete picture of the child welfare system in news coverage would include stories that are not just about when the system fails, but also about how it is serving children and their families successfully — and how it can improve. With that overarching goal in mind, we provide the below recommendations. We do not attempt to provide a detailed blueprint for practitioners’ communication strategies on this issue; rather, we provide a framework that practitioners can use as they work together to develop media strategies to shift the narrative about the child welfare system.

It’s important to remember that, as with any other issue, the first step in developing media and messaging strategies is clarifying your overall strategy: what needs to change, how to change it, and why it needs to be changed. This means identifying the problem you want to address, a specific solution, and the people who have the power to make that change. It also means clarifying why you think this change is important so that you can articulate your goals in terms of shared values, such as community, safety, or protecting the vulnerable.

For example, you might be concerned that child welfare agencies in your state are not effectively engaging with domestic violence offenders, and therefore missing an opportunity to reduce harm to their partners and children. One solution might be to provide funding and other resources for innovative programs that address this issue. In your media strategy to gather support for this solution, you’d want to consistently express the values that drive you to seek this change (perhaps our responsibility to do everything possible to keep children safe), not just the nitty-gritty details of how much funding and for what.

Then, it’s important to consider the audience that needs to be influenced and the messengers that will have the greatest impact for that audience. In some cases, the most persuasive messengers might be social workers, but in others it might be teachers or domestic violence practitioners. What messages are most effective in any given situation will depend on your overall strategy, who you’re trying to reach, who is delivering the message, and the overall political and cultural context.

Whatever problem you’re working on, part of an effective communication strategy will be addressing the gaps and misperceptions about the child welfare system that we uncovered in this news analysis. Based on those findings, we recommend that child welfare practitioners consider the following recommendations in their media and messaging strategies:

Create and use the news to paint a broader picture of how the child welfare system works in your community.

When the child welfare system appears in the news, it’s most often because something terrible has happened to a child in its charge. If practitioners want to see stories about how the child welfare system works for families and communities or stories about innovative approaches to making the system work better for everyone it serves, they will have to make successes and solutions newsworthy.

One approach is to create news that focus on actions, initiatives, and policies designed to prevent child abuse and domestic violence. That could mean releasing studies, publicizing community events, giving awards, or finding other newsworthy ways to illustrate in a compelling way how the child welfare system supports and enhances the lives of children, as well as victims of domestic violence. What strategies and innovations in child welfare are taking place at the community level? At the local or state level? If these approaches are working, journalists need to know about them.

When reporters are focused on the criminal justice aspects of a high-profile case, practitioners can think about whether it’s possible and appropriate to piggyback off the media attention and bring prevention into the frame. Be ready to respond quickly to current and notable stories with strong, timely comments and actions that help illustrate what should happen next to prevent another tragedy and make the system work better for everyone — not just children, but their families as well. The case of Zymere Perkins and the New York City Administration of Children’s Services illustrated the power of generating media coverage to advance a policy agenda. As a result of the public scrutiny, Mayor de Blasio instituted a domestic violence task force to prioritize making the connection between relationship and spousal abuse and the protection of children.48

Shape the narrative by contributing opinion pieces.

We found very few opinion pieces about child welfare or the connection between child welfare and domestic violence, which means child welfare experts could be missing opportunities to shape the public and policy agendas around those issues.

Opinion pieces can be proactive or reactive; both approaches give practitioners opportunities to bring solutions to the fore. Meeting with the editorial board of a local newspaper can be a particularly effective proactive strategy because child welfare agencies and issues are so woven into the fabric of communities and regions. A well-timed editorial can be very persuasive during policy debates or funding negotiations.

Using a reactive strategy, practitioners can monitor the news and be poised to respond to stories about child welfare with timely opinion pieces. Practitioners could also write a letter to the editor to respond to problematic news coverage of the child welfare system — or to compliment a reporter for comprehensive reporting on a local child welfare issue, for example. Practitioners might also decide to follow up with the journalist directly to offer their assistance for future stories.

Whether proactive or reactive, when an opinion piece is published, practitioners should be sure that it reaches key audiences (be they funders, policymakers, or the community at large). That means reusing the news, whether by sending copies of the article or links to supporters and policymakers, or by sharing the piece on social media and other platforms to stimulate discussion.

Illustrate the context around child abuse and neglect.

No matter what your media strategy, it’s important to broaden the frame to help your audience see the context around child abuse. Illustrating the value of the child welfare system requires going beyond the simple criminal justice details of a case and showing the context in which family violence happens and how it can be prevented. That can be challenging, since the world surrounding us is crowded and complex. Practitioners will need to choose what to share, since reporters won’t have room in a single news story to depict the whole issue.

Child welfare practitioners can identify, in the current moment, what specifically they want their key audience to understand about family violence and why it happens, and then highlight the piece of the landscape that should be brought into focus to illustrate the importance of that goal. For instance, if a local practitioner wants to make the case for greater cooperation between the child welfare system and domestic violence service providers, they might provide reporters with local statistics about the extensive overlap between the two issues.3, 4

Though time constraints and editing may limit how much context is included in a single story, practitioners can improve the chances that their comments will be included if they use social math (statistical comparisons that make numbers meaningful), media bites (short, memorable statements), visuals, and other story elements that make it easier for reporters to tell the systems part of the story.

When submitting visuals, it’s important for child welfare experts to think critically about the images they create and disseminate to journalists when pitching stories or providing resources. We know that families of color are overrepresented in the child welfare system and that photos in the news mirror that overrepresentation. What sorts of photo opportunities could help challenge harmful stereotypes, address issues of inequity, and illustrate the connections between domestic violence and child welfare?

Help reporters see the connections between domestic violence and child welfare — and why they matter.

Practitioners are well aware of the links between child abuse and domestic violence, but those connections may not be visible to the general public or to policymakers. News coverage seldom illustrates them; few stories even mention both issues in the same article. If the experts who know these issues best can illustrate the overlap between them, it will be easier to make the case for promising practices that bridge systems and strengthen the child welfare system. When practitioners talk to reporters with the goal of elevating those connections in mind, they should be ready to provide them with contact information for sources and concrete examples of how the systems can intersect in ways that help children and their families.

Recommendations for journalists

Reporting on child welfare presents unique challenges. In many newsrooms, reporters, including those assigned to cover crimes, lack sufficient training on the complexities and sensitive nature of family violence, especially when it involves children. To meet that need, a number of organizations have outlined general recommendations that focus on interviewing techniques, confidentiality concerns, and other specifics when reporting on children and victims of violence to help reporters craft responsible and complete articles.49-52 Here we focus on how journalists — whether they are on the crime or city politics beat — can build on our findings to tell a more complete story about the child welfare system, including its intersections with domestic violence.

Interview sources beyond the criminal justice system.

Because it is often focused on specific incidents of child abuse, the news about child welfare is, perhaps not surprisingly, dominated by criminal justice representatives. These sources and their perspectives are valuable. But family violence isn’t just a criminal justice issue: Sources like community members, faith leaders, and medical professionals can provide important and overlooked perspectives. These sources may also be able to suggest compelling ideas for underexplored stories, such as concerns about racial disparities within the child welfare system and how these impact families and communities.

Time constraints and breaking news can make it challenging to connect with unfamiliar sources outside of criminal justice. One solution for reporters working on the crime beat is to reach out to practitioners, researchers, or advocacy groups in advance. Practitioners in particular can often connect reporters quickly with diverse sources, such as survivors of domestic violence or child abuse who are willing to talk to reporters about their experiences with the child welfare system or other experts, such as researchers who are exploring how to make stretched agencies work better.

Ask questions about the context around child welfare issues.

Child abuse and maltreatment has deep roots and far-reaching consequences for families and whole communities — in fact, it often coincides with other types of violence, like domestic violence. Illuminating the landscape beyond individual cases of abuse and institutional failures can help more readers and viewers connect with the story and understand the role of community members in ensuring that our systems function well. Reporters working on stories about local government and the child welfare system, for example, could ask questions about what readers should know about family violence locally, whether other types of family violence — like domestic violence — are also part of the story, or how the child welfare system is working to prevent and address child abuse and neglect.

Report on problems, but also investigate solutions.

We found that the news about child welfare often centers on specific cases of abuse, failures of the child welfare system, and punitive, after-the-fact ways of addressing these issues. But if the coverage stops there, the public will learn little about what would be needed to address the root causes of these problems. For example, the news could include discussions about preventing child abuse and domestic violence at a community level or innovative strategies for supporting the child welfare system as it faces large caseloads, staff turnover, and the challenges of volunteer or foster family recruitment.

Reporters from any beat could investigate solutions by asking their sources questions such as: What would the child welfare system need to do its job well? What has been done in other communities? Could it work here? What is happening in the community to prevent child abuse and domestic violence? What more could be done? What do child welfare practitioners or government officials think should be done? Is it reasonable? If so, why hasn’t it happened here?

Acknowledgments

This report was written by Sarah Han, BA; Laura Nixon, MPH; Pamela Mejia, MS, MPH; Daphne Marvel, BA; and Lori Dorfman, DrPH. We thank Fernando Quintero and Allison Rodriguez for their invaluable input and contributions to the development of this report and Heather Gehlert for editing support. We also thank Eleanor Davis, Brian O’Connor, Lonna Davis, and Shellie Taggart at Futures Without Violence and Jay Otto at the Center for Health and Safety Culture, Western Transportation Institute for their feedback and content expertise.

Funding for this report was provided by the Quality Improvement Center on Domestic Violence in Child Welfare of the Children’s Bureau in the Administration for Children and Families at the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (Grant #90CA1850-01). The content of this report does not necessarily reflect the view or policies of the funder, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services.

End notes

aThe term “domestic violence” is sometimes used to refer more broadly to violence that happens within the household or between family members, but, in this report, we use it specifically to describe violence between spouses and significant others. A more precise, technical term for this is “intimate partner violence,” but this phrasing is seldom used colloquially, and it never appeared in the news outlets we searched.

bThe high-profile case of Zymere Perkins’ death also involved domestic violence. However, some coverage did not mention the abuse experienced by Zymere’s mother.

References

1. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau. (2017). Child maltreatment 2015. Retrieved from: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/cm2015.pdf.

2. Child Welfare Information Gateway, Children’s Bureau, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. (2014). Domestic violence and the child welfare system. Retrieved from: https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubPDFs/domestic-violence.pdf.

3. Hamby S., Finkelhor D., Turner H., & Ormrod R. (2011). Children’s exposure to intimate partner violence and other family violence. Juvenile Justice Bulletin: Children’s Exposure to Intimate Partner Violence and Other Family Violence.

4. Spears L. (2000). Building bridges between domestic violence organizations and child protective services. National Resource Center on Domestic Violence. Retrieved from: https://vawnet.org/material/building-bridges-between-domestic-violence-organizations-and-child-protective-services.

5. Gamson W. (1992). Talking politics. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

6. McCombs M. & Reynolds A. (2009). How the news shapes our civic agenda. In: J. Bryant & M.B. Oliver (Eds.), Media effects: Advances in theory and research. (pp. 1-17). New York, NY: Taylor & Francis.

7. Scheufele D. & Tewksbury D. (2007). Framing, agenda setting, and priming: The evolution of three media effects models. Journal of Communication; 57(1): 9-20.

8. Dearing J.W. & Rogers E.M. (1996). Agenda-setting. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

9. Mejia P., Cheyne A., & Dorfman L. (2012). News coverage of child sexual abuse and prevention, 2007–2009. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse; 21(4): 470-487.

10. Nixon L., Rodriguez A., Han S., Mejia P., & Dorfman L. (2017). Issue 24: Adverse childhood experiences in the news: Successes and opportunities in coverage of childhood trauma. Berkeley, CA: Berkeley Media Studies Group. Retrieved from: https://www.bmsg.org/resources/publications/issue-24-adverse-childhood-experiences-trauma-news-coverage-successes-opportunities/.

11. McManus J. & Dorfman L. (2003). Issue 13: Distracted by drama: How California newspapers portray intimate partner violence. Berkeley, CA: Berkeley Media Studies Group. Retrieved from: https://www.bmsg.org/resources/publications/issue-13-distracted-by-drama-how-california-newspapers-portray-intimate-partner-violence.

12. Krippendorff K. (2008). Testing the reliability of content analysis data: What is involved and why? In: K. Krippendorff K. & M.A. Bock (Eds.), The content analysis reader. (pp. 350-357). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

13. Start of North Carolina Child Services overhaul given final OK. (June 14, 2017). The Associated Press.

14. Stutzman R. (2017, April 23). Accused mom: 2 1/2-year-old son killed toddler. Orlando Sentinel.

15. ACEs Too High: ACEs 101. Retrieved from: http://acestoohigh.com/aces-101/. Accessed September 1, 2018.

16. Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs). Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/acestudy. Accessed September 1, 2018.

17. Iyengar S. (1991). Is anyone to blame? How television frames political issues. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

18. Dorfman L., Wallack L., & Woodruff K. (2005). More than a message: Framing public health advocacy to change corporate practices. Health Education & Behavior; 32(4): 320-336.

19. Kitzinger J. & Skidmore P. (1995). Playing safe: Media coverage of child sexual abuse prevention strategies. Child Abuse Review; 4: 47-56.

20. Carlyle K.E., Slater M.D., & Chakroff J.L. (2008). Newspaper coverage of intimate partner violence: Skewing representations of risk. Journal of Communication; 58(1): 168-186.

21. Hawkins K.W. & Linvill D.L. (2010). Public health framing of news regarding childhood obesity in the United States. Health Communication; 25(8): 709-17.

22. Major L.H. (2009). Break it to me harshly: The effects of intersecting news frames in lung cancer and obesity coverage. Journal of Health Communication; 14(2): 174-188.

23. Yetter D. (2016, November 16). Social workers plead for state help. Courier Journal.

24. Mitchell M. (2017, May 31). When meth is mixed with parenting, the results can be fatal. Fort Worth Star-Telegram.

25. Byers C. (2017, June 13). Parents of girl found dead in Metro East garage appear in Las Vegas court. St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

26. Mitchell M. (2017, May 5). Mitchell: Child-welfare system continues to fail at-risk kids. Chicago Sun-Times.

27. Ortega B. (2017, June 4). How the system failed Devani. The Arizona Republic.

28. Bain G. (2017, January 30). De Blasio defends ACS to state lawmakers, calls media portrayal of child welfare agency unfair. New York Daily News.

29. Horn D. (2016, October 19). Reforms still needed a year after child’s death. The Cincinnati Enquirer.

30. Dorfman L. & Schiraldi V. (2001). Off balance: Youth, race & crime in the news. Building Blocks for Youth. Retrieved from: http://bmsg.org/sites/default/files/bmsg_other_publication_off_balance.pdf.

31. McManus J. & Dorfman L. (2000). Issue 9: Youth and violence in California newspapers. Berkeley, CA: Berkeley Media Studies Group. Retrieved from: https://www.bmsg.org/resources/publications/issue-9-youth-and-violence-in-california-newspapers.

32. Dorfman L., Mejia P., Cheyne A., & Gonzalez P. (2011). Issue 19: Case by case: News coverage of child sexual abuse. Berkeley, CA: Berkeley Media Studies Group. Retrieved from: https://www.bmsg.org/resources/publications/issue-19-case-by-case-news-coverage-of-child-sexual-abuse.

33. Bekiempis V. & Schapiro R. (2017, February 2). Child welfare workers sue ACS for allegedly demoting them amid Zymere Perkins probe even though they weren’t involved. New York Daily News.

34. Ramer H. (2017, June 1). Senate approves budget, policy change bill yet to pass. The Associated Press.

35. New Mexico officials invest $3M in new child abuse program. (2017, June 28). The Associated Press.

36. Silverman T. (2017, June 23). Opioid epidemic is traumatizing kids. The Indianapolis Star.

37. Crepeau M. (2017, June 9). 18-year-old man charged in infant daughter’s death. Chicago Tribune.

38. Wilusz L. (2017, March 3). Infant daughter of man charged with beating pregnant fiancee dies. Chicago Sun-Times.

39. Domestic incident leads to discovery of handgun. (2017, May 6). The Buffalo News.

40. Miami Herald Editorial Board. (2016, August 24). New laws mean little when DCF fails kids. Miami Herald.

41. Child Welfare Information Gateway, Children’s Bureau, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. (2016). Racial disproportionality and disparity in child welfare. Retrieved from: https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubpdfs/racial_disproportionality.pdf.

42. Daily News Editorial Board. (2016, September 28). Murdered on Bill’s watch: The death of 6-year-old Zymere Perkins must lead to a new era of child welfare accountability. New York Daily News.

43. Suhr J. (2017, May 8). Kansas bail bondsman gets life for killing son fed to pigs. The Associated Press.

44. St. Louis Post-Dispatch Editorial Board. (2016, December 4). Editorial: Protecting children, as well as the unborn. St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

45. Durkin E. (2016, December 15). ‘The city failed,’ Blaz aide: Cascade of errors doomed Zymere. New York Daily News.

46. The Oklahoman Editorial Board. (2017, February 8). Opening of Family Justice Center is good news for OKC. The Oklahoman.

47. Lovece F. (2017, March 30). Robin Thicke, Paula Patton near custody settlement, report says. Newsday.

48. Let Jaden be last kid failed by the child welfare system. (2016, December 1). New York Daily News.

49. Teichroeb R. (2006). Covering children & trauma: A guide for journalism professionals. Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma. Retrieved from: https://dartcenter.org/sites/default/files/covering_children_and_trauma_0.pdf.

50. National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. (2012). Guidance for media reporting on child abuse and neglect in Northern Ireland. Retrieved from: https://www.basw.co.uk/system/files/resources/basw_21709-5_0.pdf.

51. Morgan B. (2017, February 25). What are the best practices for media reporting on child welfare? The Discourse. Retrieved from: https://www.thediscourse.ca/child-welfare/best-practices-media-reporting-child-welfare.

52. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018). Suggested practices for journalists reporting on child abuse and neglect. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/childmaltreatment/journalists-guide.pdf.